MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Asymmetric Ionospheric Jets in Jupiter's Aurora

By Ruoyan Wang (University of Leicester)

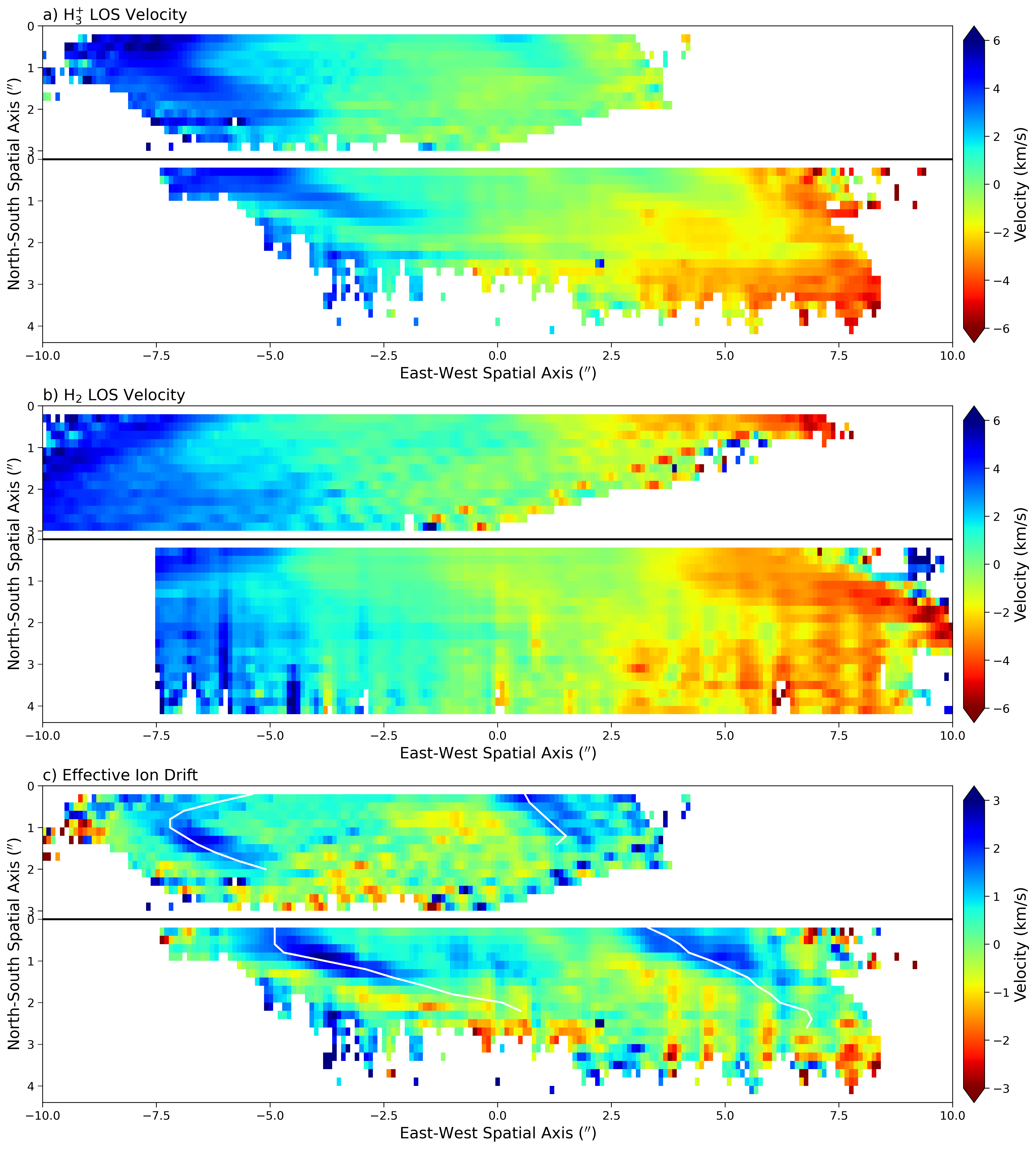

We have simultaneously observed line-of-sight ionospheric and thermospheric winds in Jupiter using the Keck II telescope and produced one of the first global maps of both ion and neutral flows in the same layer of any atmosphere. Since ionospheric currents are through the relative motion of ions within the neutral atmosphere, comparing these two maps produces a global map of the "effective" ion drifts, the E x B flows that drive upper ionospheric currents. To the surprise of the Jupiter community, this upper atmospheric "effective" ion drift is dominated by two sunward blue-shifted jets associated with the dawn and dusk main auroral region, highly reminiscent of ionospheric flows seen on Earth. This discovery is directly opposite to the expected rotationally symmetric breakdown in corotation driven by the plasma-heavy magnetosphere. Our result suggests that the asymmetric currents close in the upper ionosphere, while the closure of breakdown-in-corotation currents occurs deep in the lower ionosphere, resulting in powerful upward auroral currents penetrating through overlying regions of downward currents associated with the asymmetric currents. Such a mechanism could potentially explain the complex switching generation of Jupiter's main auroral emissions observed by the Juno mission. Moreover, this study highlights the importance of the neutral atmosphere and interactions between ions and neutrals on other planets, including Earth, making Jupiter an important global comparator for future studies of these interactions.

See full paper for further details:

Wang, R., Stallard, T. S., Melin, H., Baines, K. H., Achilleos, N., Rymer, A. M., Ray, R. C., Nichols, J. D., Moore, L., O'Donoghue, J., Chowdhury, M. N., Thomas, E. M., Knowles, K. L., Tiranti, P. I., Miller, S. (2023). Asymmetric Ionospheric Jets in Jupiter's Aurora. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 128, e2023JA031861. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA031861.

The closest-to-the-Sun-ever direct observation of a shock wave and its heliospheric journey

By Domenico Trotta (Imperial College London)

Shock waves, i.e., abrupt transitions between supersonic and subsonic flows, are present in a large variety of astrophysical systems, and are pivotal for efficient energy conversion and particle acceleration in our universe [1]. Despite decades of research, the mechanisms by which particles are accelerated at shocks are a matter of debate, and are crucial to several applications, ranging from explaining acceleration of cosmic rays to the highest energies [2] to the study of space weather phenomena [3].

Shocks in the heliosphere are unique, being directly accessible by spacecraft exploration, thus providing the missing link to the remote observations of astrophysical systems. Interplanetary (IP) shocks are generated because of solar activity phenomena, such as Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), and play an important role in the energetics of the heliosphere where they propagate [4].

The ground-breaking NASA Parker Solar Probe (PSP, [5]) and ESA Solar Orbiter [6] missions are probing the previously unexplored inner heliosphere, providing datasets with unprecedented resolutions.

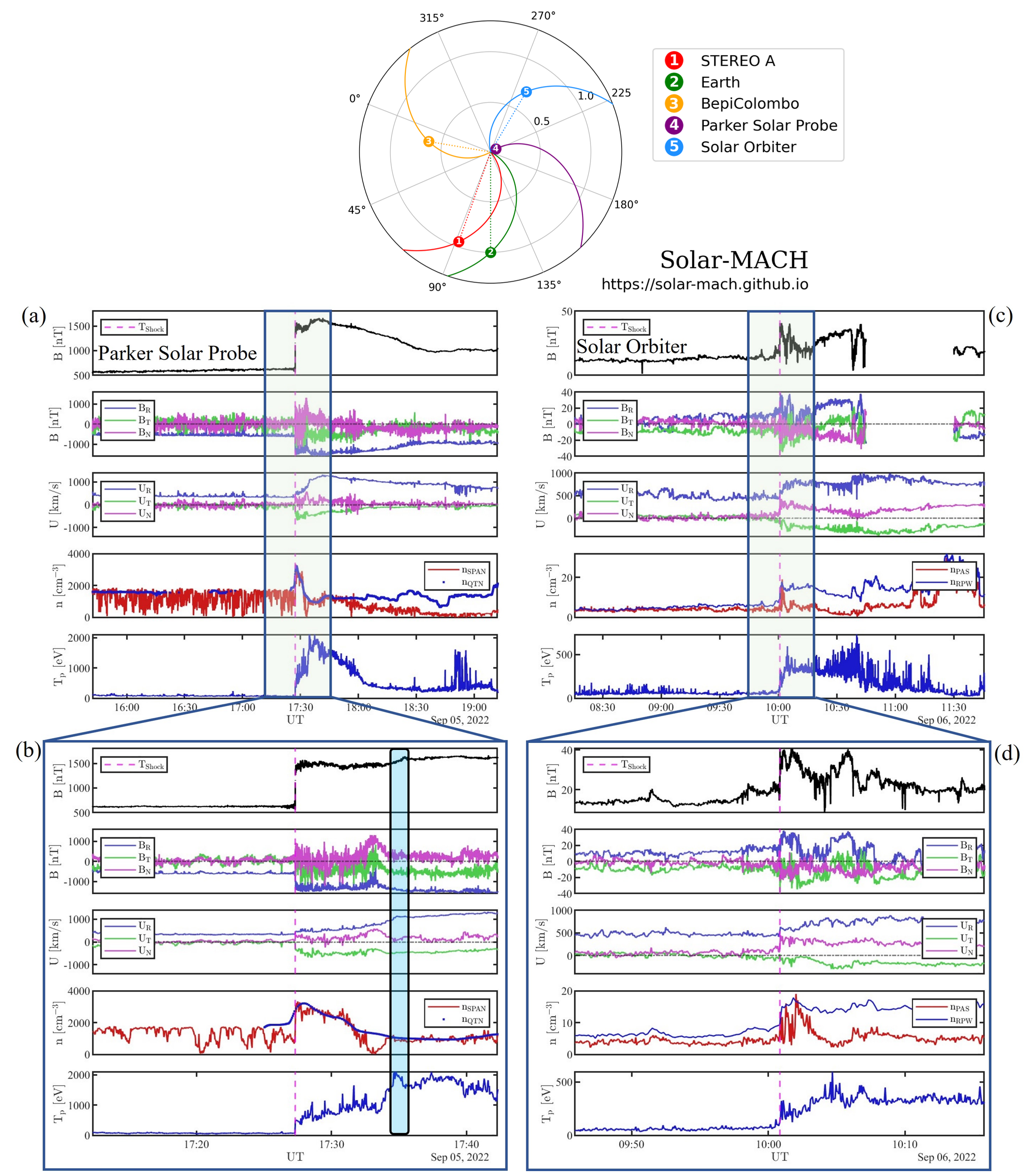

We used such novel observational window to report direct PSP observations of a CME-driven shock as close to the Sun as 0.07 A, making it the closest to the Sun direct observation of a shock wave to date. The shock then reached Solar Orbiter at 0.7 AU, enabling us to study the evolution of the shock throughout its propagation in the heliosphere.

We characterized the shock and its environment. At PSP, we found a sharp shock with moderate strength, and investigated how switchbacks, fundamental constituents of the near-Sun environment, are processed by the shock crossing. In contrast, the Solar Orbiter observations revealed a very structured shock transition, with shock-accelerated protons with energies of up to 2 MeV. The differences between the two shocks are due to both evolution effects and the large-scale geometry of the event, crossed by the spacecraft in two points only. This study elucidates how the local features of IP shocks and their environments can be very different as they propagate through the heliosphere.

See full publication for further information:

Trotta et al., ApJ, 962, 2 (2024), DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad187d

References:

[1] Bykov et al., SSRv, 2015, 14 (2019)

[2] Amato&Blasi, Adv. Sp. Res., 62, 10 (2018)

[3] Klein&Dalla, SSRv, 212, 1107 (2017)

[4] Reames et al., ApJ, 483, 512 (1997)

[5] Fox et al., SSRv, 204, 7 (2016)

[6] Muller et al., A&A, 642, A1 (2020)

The Impact of Non-Equilibrium Plasma Distributions on Solar Wind Measurements by Vigil's Plasma Analyser

Hongjie Zhang (University College London)

Space weather, originating from the Sun, has a profound impact on human life. An effective space weather monitor is crucial for detecting severe space weather events and providing early warnings before they reach Earth. The European Space Agency is currently preparing to launch the Vigil mission as a space-weather monitor at the fifth Lagrange point of the Sun-Earth system. Vigil will carry, amongst other instruments, the Plasma Analyser (PLA) to provide quasi-continuous measurements of solar wind ions.

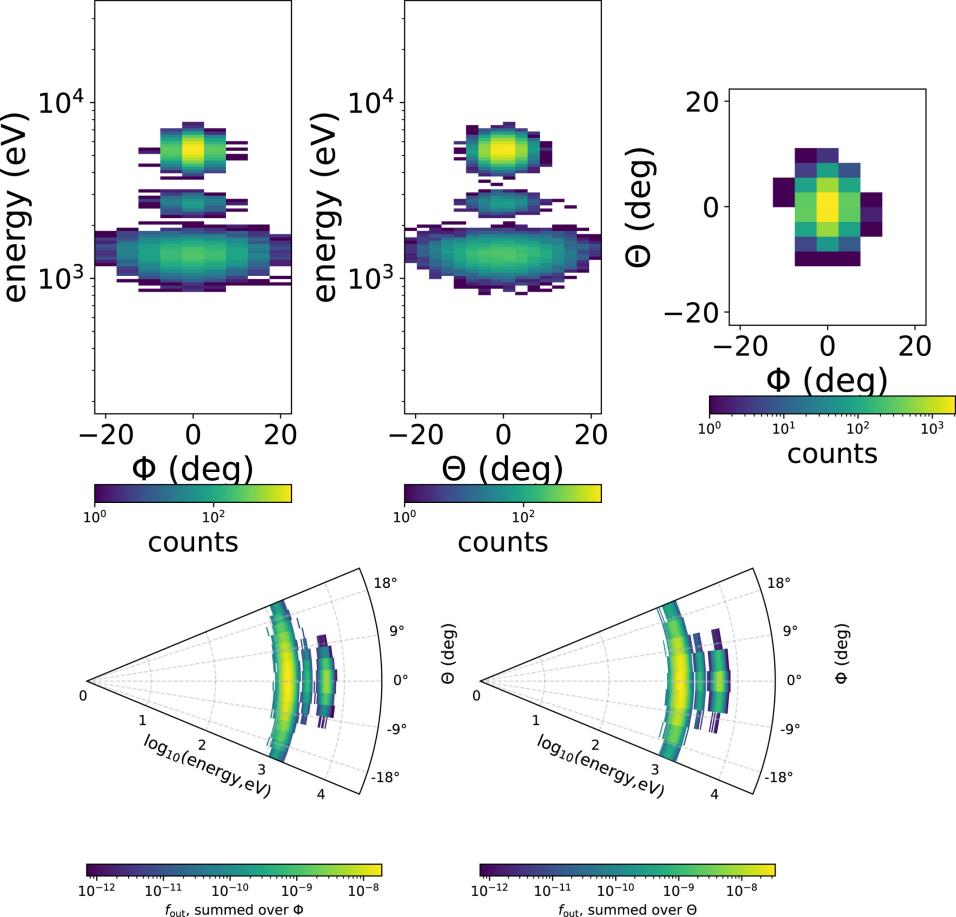

In this study, we model the performance of the PLA instrument. We employ a forward-modeling technique, which involves predicting measurements (number of particle counts in energy, elevation, and azimuth) based on typical solar wind properties. Then we utilize backward-modeling based on the predicted measurements. This approach allows us to compare the expected observations of the PLA with the assumed input conditions of the solar wind. We evaluate the instrument performance under realistic, non-equilibrium plasma conditions, accounting for temperature anisotropies, proton beams, and the contributions from alpha-particles. We examine the accuracy of the instrument’s performance over a range of input solar wind properties. We recommend potential improvements such as applying ground-based fitting techniques to obtain more accurate measurements of the solar wind even under non-equilibrium plasma conditions. The use of ground processing of plasma moments instead of on-board processing is crucial for the extraction of reliable measurements.

See publication for details:

Zhang, H., Verscharen, D., & Nicolaou, G. (2024). The impact of non-equilibrium plasma distributions on solar wind measurements by Vigil's Plasma Analyser. Space Weather, 22, e2023SW003671. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023SW003671

The challenge to understand the zoo of particle transport regimes during resonant wave-particle interactions for given survey-mode wave spectra

By Oliver Allanson (University of Birmingham; University of Exeter)

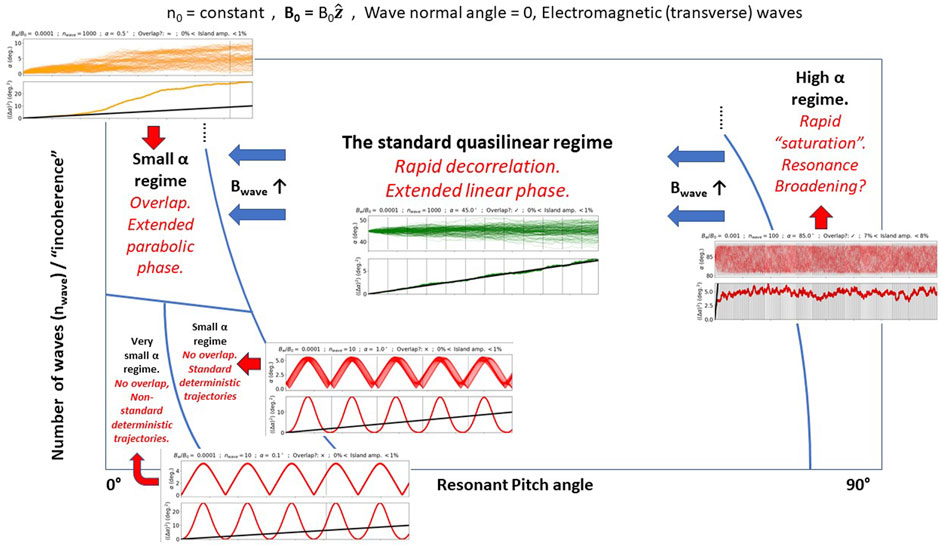

Quasilinear theories have been shown to well describe a range of transport phenomena in magnetospheric, space, astrophysical and laboratory plasma “weak turbulence” scenarios. It is well known that the resonant diffusion quasilinear theory for the case of a uniform background field may formally describe particle dynamics when the electromagnetic wave amplitude and growth rates are sufficiently “small”, and the bandwidth is sufficiently “large”.

However, it is important to note that for a given wave spectrum that would be expected to give rise to quasilinear transport, the theory may apply for a given range of resonant pitch-angles and energies, but may not apply for some smaller, or larger, values of resonant pitch-angle and energy. That is to say that the applicability of the quasilinear theory can be pitch-angle dependent, even in the case of a uniform background magnetic field. If indeed the quasilinear theory does apply, the motion of particles with different pitch-angles are still characterised by different timescales.

Using a high-performance test-particle code, we present a detailed analysis of the applicability of quasilinear theory to a range of different wave spectra that would otherwise “appear quasilinear” if presented by e.g., satellite survey mode data. We present these analyses as a function of wave amplitude, wave coherence and resonant particle velocities (energies and pitch-angles). In doing so, we identify and classify five different transport regimes (see figure) that are a function of particle pitch-angle.

The results in our paper demonstrate that there can be a significant variety of particle responses (as a function of pitch angle) for very similar looking survey-mode electromagnetic wave products, even if they appear to satisfy all appropriate quasilinear criteria.

In recent years there have been a sequence of very interesting and important results in this domain, and we argue in favour of continuing efforts on: (i) the development of new transport theories to understand the importance of these, and other, diverse electron responses; (ii) which are informed by statistical analyses of the relationship between burst- and survey-mode spacecraft data.

For full details see https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2024.1332931

SpaceSSL – Automatic Encoding to Find Similar Observations

By Andy Smith (Northumbria University)

We often have large, unlabelled datasets in space physics, where the phenomenon of interest only appears rarely. Understanding the underlying physics of the system from rare observations is a challenge, and locating complementary, similar observations in large datasets can be prohibitively time consuming.

In this work we present an automated, self-supervised method by which the key information from two dimensional data can be encoded into a smaller vector representation. This representation (encoding/embedding) contains the key information describing the data; we can then use the distance between vectors to assess the similarity of the observations.

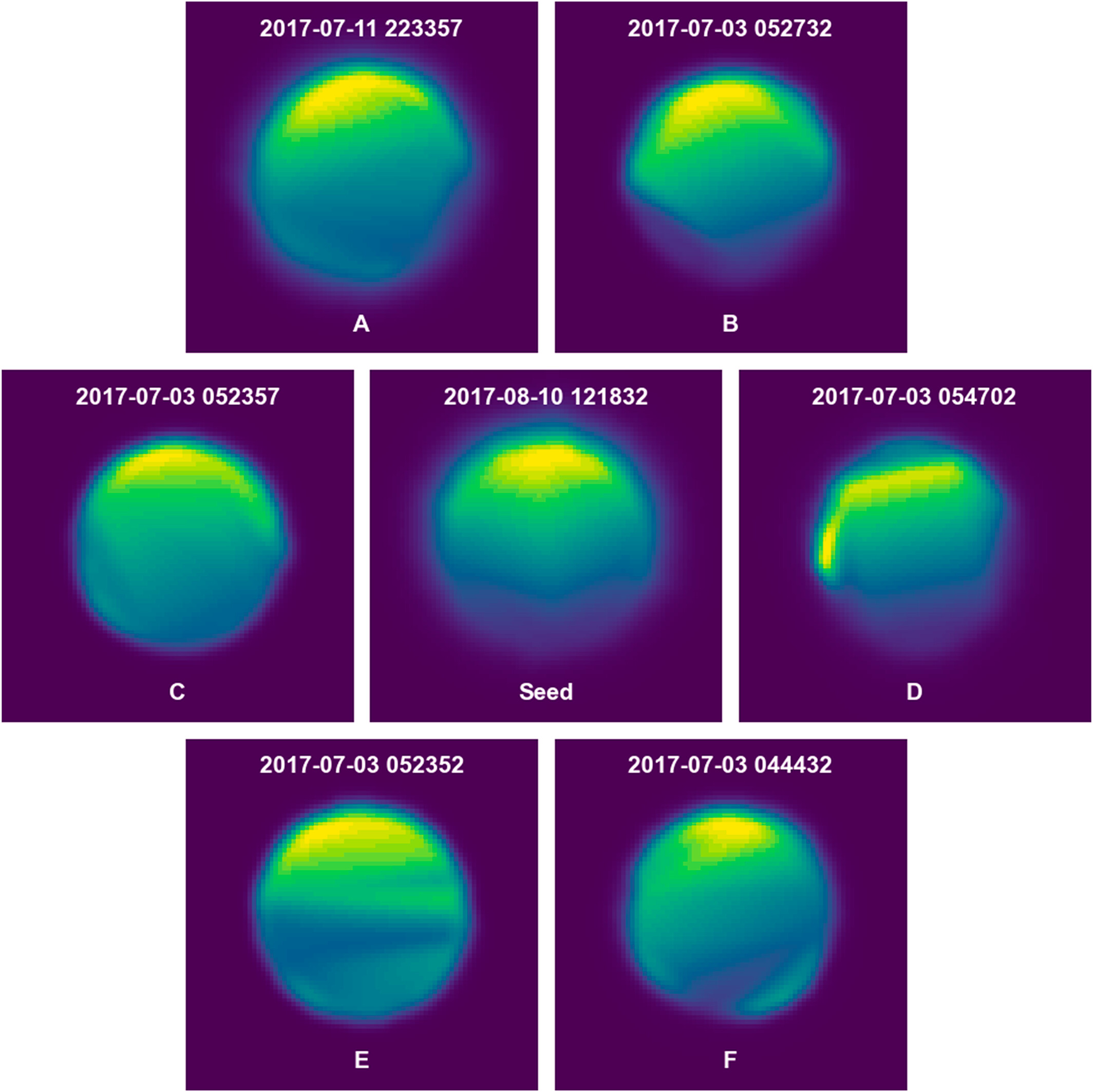

We showed the potential of this method with two example datasets – spacecraft in situ electron velocity distributions and auroral all sky images. For both datasets we provided the method with a library of over five thousand images, which were then effectively and automatically summarized by the model.

In the case of the electron distributions, we tested a “seed” image of a rare phenomena – corresponding to the region of space near the site of magnetic reconnection. In this region the electron distribution takes a characteristic crescent or arc-like shape [Figure 1, centre]. We can then extract the six closest partners of this image, using the distance between the embedding vectors. The two closest neighbours of the seed image (A and B in Figure 1) represent two separate previously published case study examples known to be close to the site of magnetic reconnection.

This method promises to be a useful tool in locating interesting phenomena in large datasets, providing an efficient method for moving from case studies to thorough statistical surveys. Code to train an example model is available at: https://github.com/SmithAndy005/SpaceSSL .

See publication for details:

Smith, A. W., Rae, I. J., Stawarz, J. E., Sun, W. J., Bentley, S., & Koul, A. (2024). Automatic encoding of unlabeled two dimensional data enabling similarity searches: Electron diffusion regions and auroral arcs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 129, e2023JA032096. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA032096