MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Modeling and Observations of the Effects of the Alfvén Velocity Profile on the Ionospheric Alfvén Resonator

By Rosie Hodnett (University of Leicester)

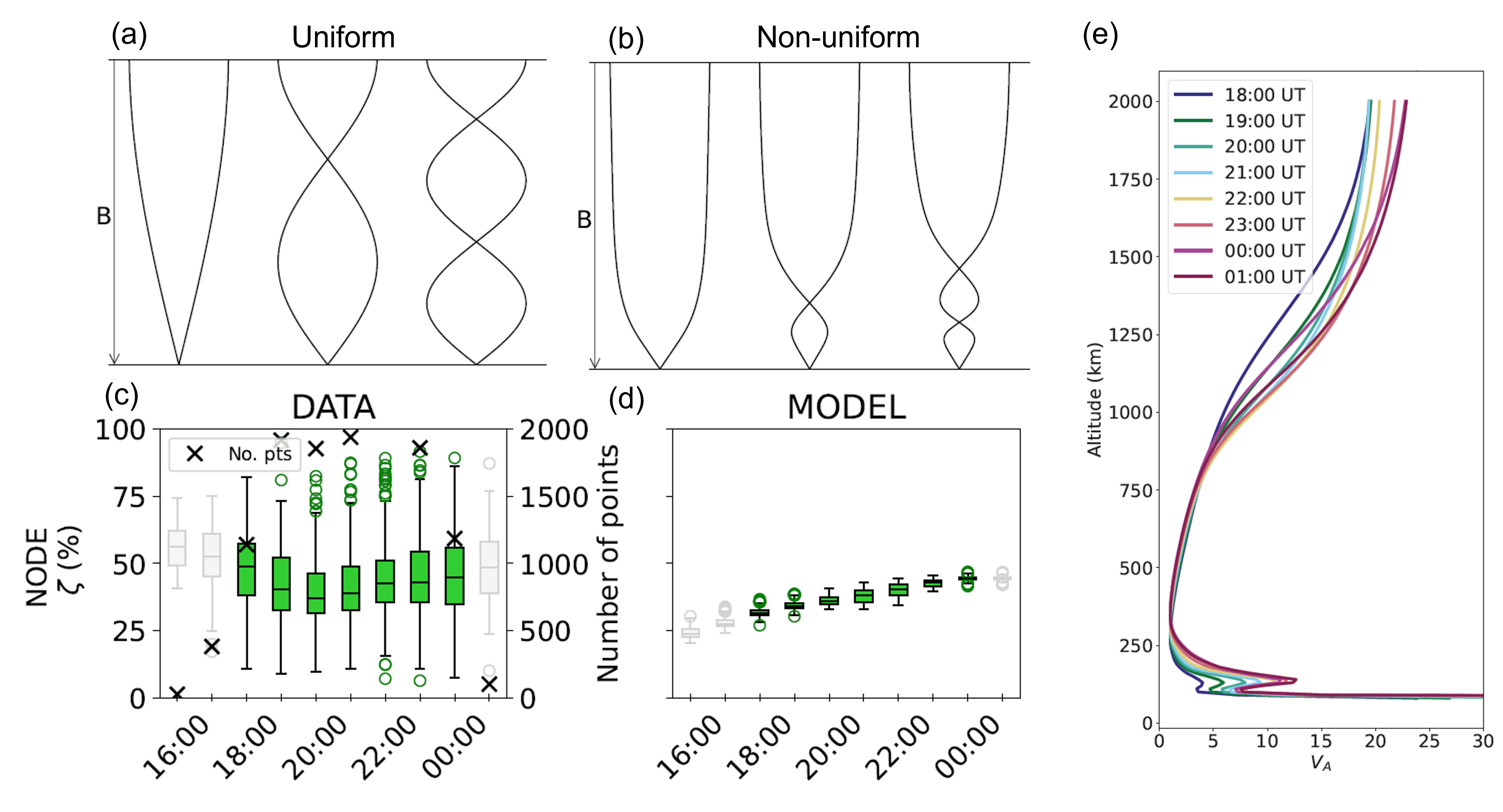

The Ionospheric Alfvén Resonator (IAR) occurs when Alfvén waves partially reflect from boundaries in the ionosphere, towards the bottom of the ionosphere and above the F-region peak. The frequencies of the IAR are strongly controlled by the plasma mass density in the ionosphere, which is not uniform.

We have observed IAR in induction coil magnetometer data at Eskdalemuir, UK (BGS site), and extracted the harmonic frequencies for nine years of data. To model the harmonic frequencies, we used the International Reference Ionosphere and the International Geomagnetic Reference Field to model Alfvén velocity profiles. By solving a one-dimensional wave equation, we modelled the first five harmonics of the IAR for times where we had data. The wave structure of the electric field for a uniform case is shown in panel (a), and the resulting modelled harmonics for a non-uniform case is shown in panel (b). We modelled the frequencies with the lower boundary condition of the electric field of the wave being a node (shown in the figure below) and an antinode. By looking at the percentage difference between the fundamental frequency and the average separation of the harmonics (ζ) for both the node and antinode models and comparing this with the data, we find that the lower boundary is closest to being a node. ζ is presented for the node case, with UT, in panels (c) and (d), which show the data and the model respectively, binned by UT. The trend of increasing ζ towards midnight is due to changing Alfvén velocity profiles (shown in panel (e)), and suggests that the ionosphere is becoming more non-uniform. As such, measurements of IAR could be used to gain insight into the shape of the Alfvén velocity profile of the ionosphere.

BGS induction coil magnetometer data, search for 'induction coil': https://webapps.bgs.ac.uk/services/ngdc/

accessions/index.html

See publication for further information:

Hodnett, R. M., Yeoman, T. K., Beggan, C. D., & Wright, D. M. (2024). Modeling and observations of the effects of the Alfvén velocity profile on the Ionospheric Alfvén Resonator. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 129, e2023JA032308. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA032308

Topology of turbulence within collisionless plasma reconnection

Bogdan Hnat (University of Warwick)

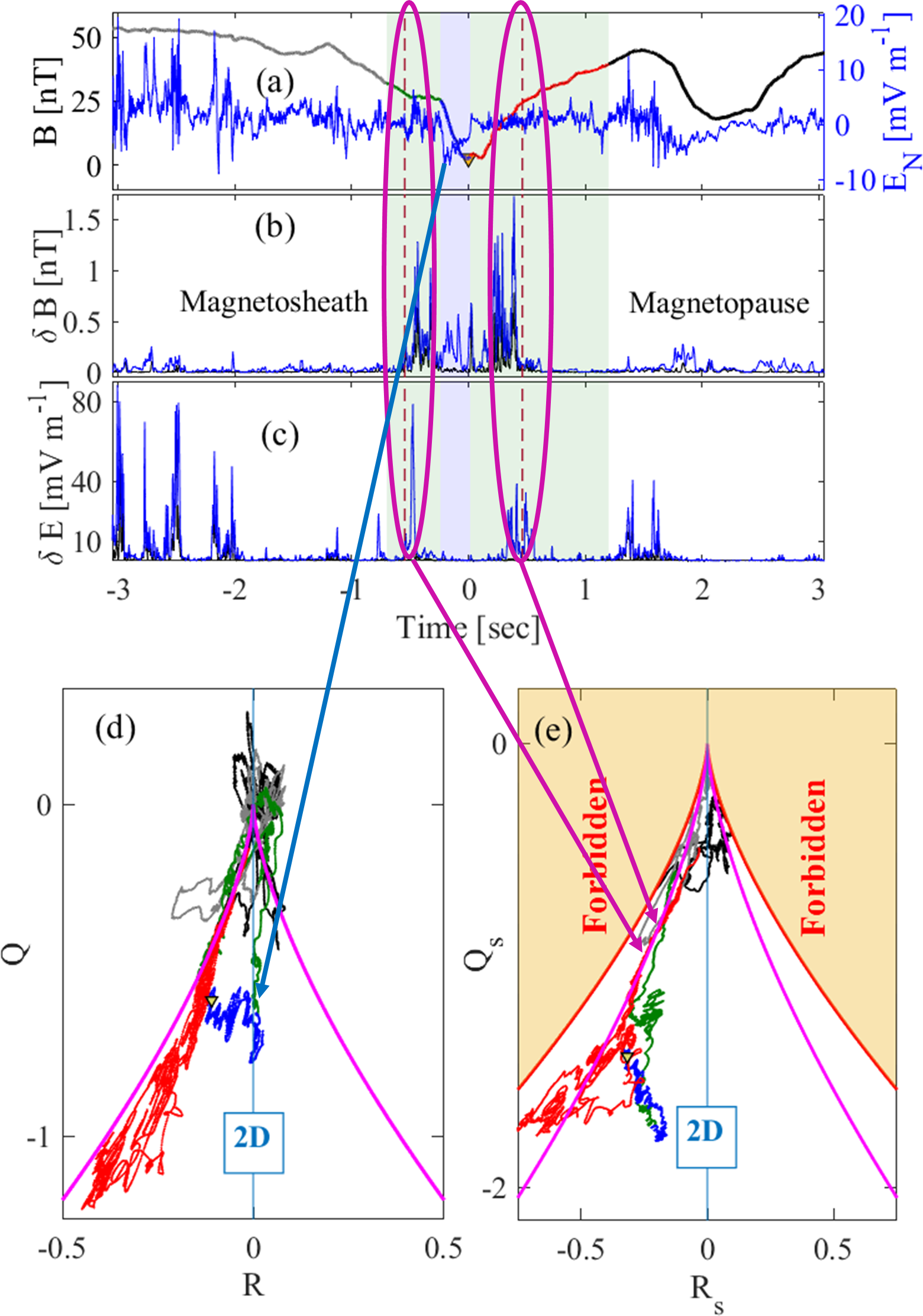

Collisionless magnetic reconnection [1] and plasma turbulence [2] are fundamental mechanisms that transfer energy across scales and between electromagnetic fields and particles. Stretched turbulent vortices and thin reconnection current sheets are prime sites of plasma heating and particle acceleration. Magnetic field line topology is central to both these processes.

We have classified the magnetic field topology observed as the four MMS spacecraft fly through a well resolved reconnection site. The MMS spacecraft separation defines a spatial 'yardstick', which is of order of the ion inertial range di, for sampling magnetic field topology. However, spatial variation of the topology is indirectly captured on a much finer spatial scale due to high time resolution of the magnetic field measurements, 8192 samples per second.

We find two distinct types of the magnetic field line topology near and at the electron dissipation region (EDR). At the edges of the EDR turbulent-like topology, identical to the topology of stretched vortices in hydrodynamic turbulence, is dominant. It coincides with large high-frequency electromagnetic perturbations. At the EDR the topology departs from turbulence and the structures appear to be two-dimensional, coinciding with suppression of electromagnetic fluctuations. The topology of the magnetic field line directly orders electron acceleration and heating. Suprathermal electrons are absent where turbulent-like topology dominates, but the bulk electron temperature anisotropy is enhanced. Reduced two-dimensional topology at the EDR coincides with the suprathermal electrons. The turbulent-like topology can arise in EMHD in scales smaller than electron inertial scale when vorticity dominates the dynamics. We find that vorticity is indeed dominant at all times within our interval.

References:

[1] J. Birn, E.R. Priest, Reconnection of Magnetic Fields: Magnetohydrodynamics and Collisionless Theory and Observations (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2007).

[2] Matthaeus, W.H. and Velli, M.,Space Science Reviews, 160(1), pp.145-168 (2011).

See publication for further information:

Hnat, Bogdan, Sandra Chapman, and Nicholas Watkins. "Topology of turbulence within collisionless plasma reconnection." Scientific Reports 13.1 (2023): 18665.

Plasma vorticity in the high-latitude ionosphere

By Gareth Chisham (British Antarctic Survey)

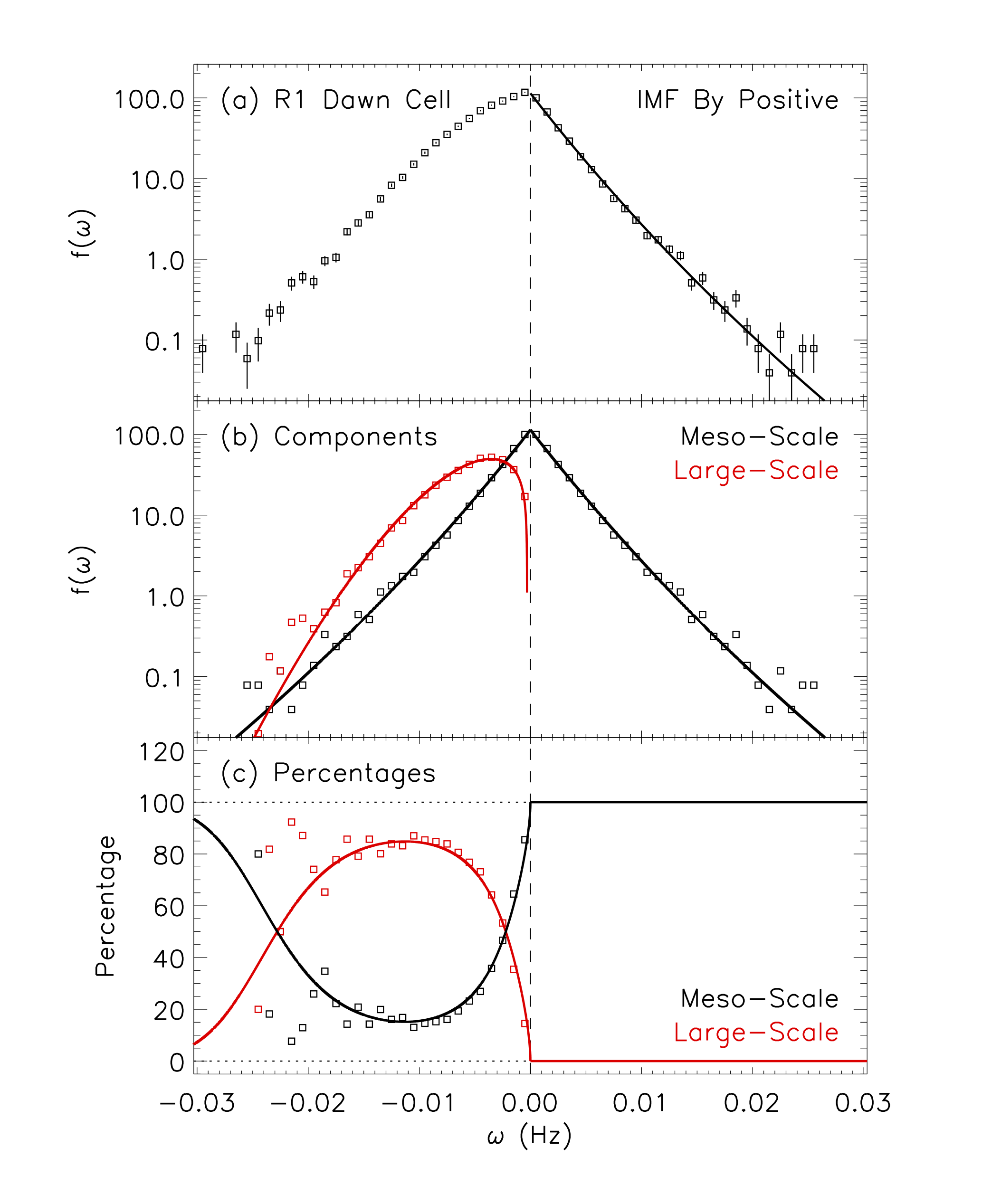

Measurements of ionospheric plasma flow vorticity can be used for studying ionospheric plasma transport processes, such as convection and turbulence, over a wide range of spatial scales. This study presents an analysis of probability density functions (PDFs) of ionospheric vorticity for selected regions of the northern hemisphere high-latitude ionosphere as measured by the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) over a 6-year interval (2000-2005 inclusive). Making certain assumptions, the observed asymmetric vorticity PDFs can be decomposed into two separate components: (1) A single-sided function that results from the large-scale vorticity inherent in the ionospheric convection pattern, driven by magnetic reconnection; (2) A symmetric double-sided function that results from meso-scale vorticity that derives from fluid processes such as turbulence, and from measurement uncertainties.

Being able to model ionospheric vorticity in this way will help to improve models of ionospheric plasma flow that are often used in larger-scale system models. At the present time, these plasma flow models typically only consider the larger-scale convection flow. Our observation of a significant meso-scale flow vorticity component due to turbulence will have implications for the fidelity of these models.

See paper for further details: Chisham, G. and Freeman, M. P. (2023). Separating contributions to plasma vorticity in the high-latitude ionosphere from large-scale convection and meso-scale turbulence. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 128, e2023JA031885, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JA031885.

Detection of the northern infrared aurora at Uranus using the W.M. Keck II Telescope and NIRSPEC instrument

By Emma Thomas (University of Leicester)

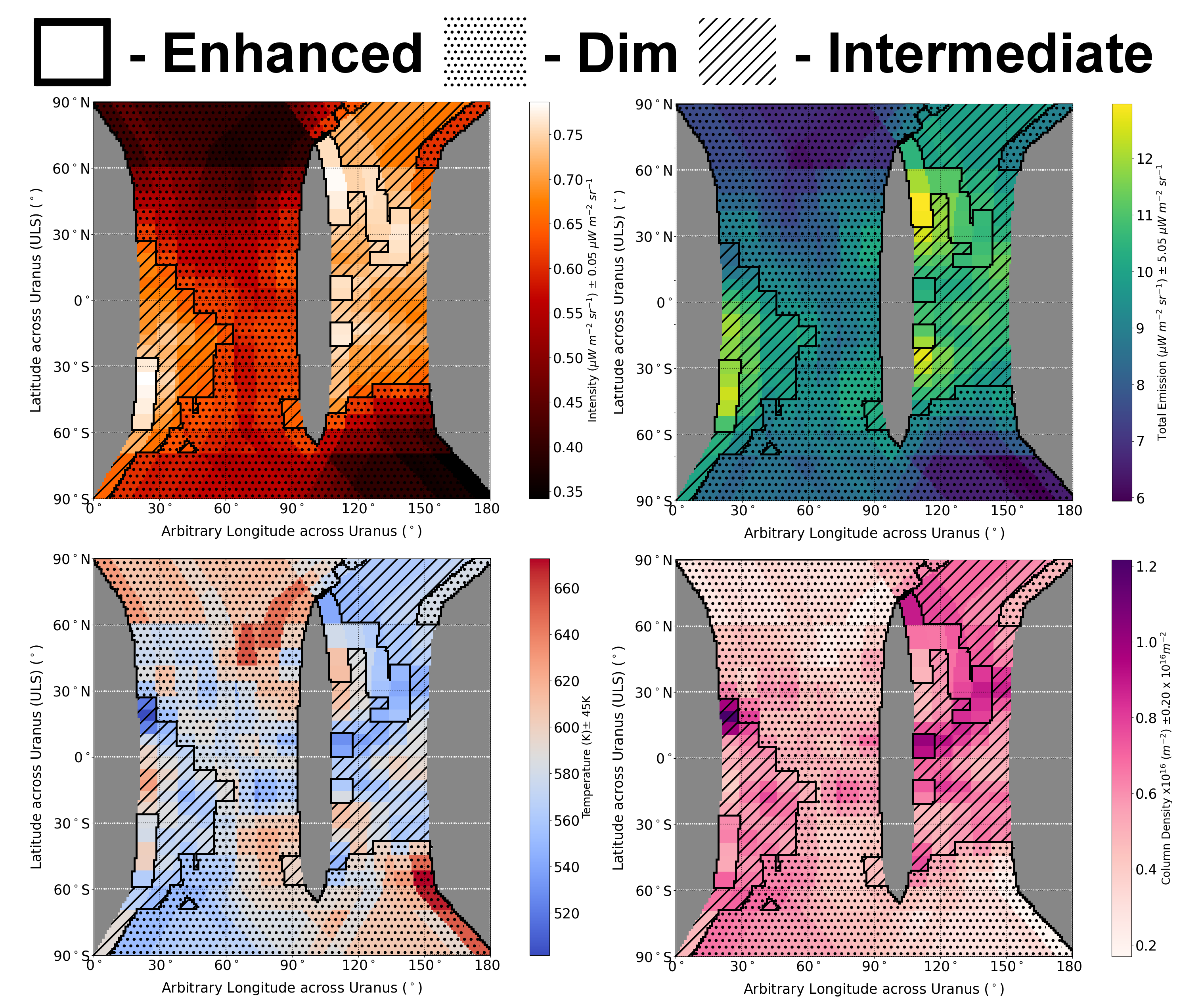

Three decades of searching for the infrared aurorae finally come to a successful conclusion as portions of the northern (IAU southern) aurorae have been confirmed at Uranus. The icy planet represents an enigma within our solar system, with the first and only visit by Voyager II in 1986, it remains one of the least documented planets in our solar system. This is exceptionally apparent with the planet’s history of auroral observations, where the UV aurorae have been observed a handful of times but no infrared (IR) counterpart has been confirmed, despite both aurorae appearing at Jupiter and Saturn. Analysis of IR aurorae at both Jupiter and Saturn have challenged what we know about magnetosphere-ionosphere coupling, highlighting a need for IR analysis at Uranus to uncover its mysteries. Since 2020 our team has meticulously analysed archived data of Uranus during 2006 from the Keck II telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawai’i. The timing of these observations was key, close to equinox, as it provided an optimal view of the predicted locations of the northern and southern aurorae. By examining the emission lines from these aurorae (the emitting ion being H3+) between 3.94 to 4.01 μm, we carried out a full spectrum best fit across 5 fundamental lines for each spatial pixel across the planet’s disk. By comparing these lines at specific locations, we were able to identify an average 88% increase in column ion densities with no significant temperature changes localised close to or at expected auroral locations for the northern aurora. With this confirmation at Uranus, we look forward to a new age of auroral investigations at both ice giant planets.

References:

Thomas, E.M., Melin, H., Stallard, T.S. et al. Detection of the infrared aurora at Uranus with Keck-NIRSPEC. Nat Astron (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-023-02096-5

A Model of High Latitude Ionospheric Convection derived from SuperDARN radar EOF Data

By Mai Mai Lam (British Antarctic Survey)

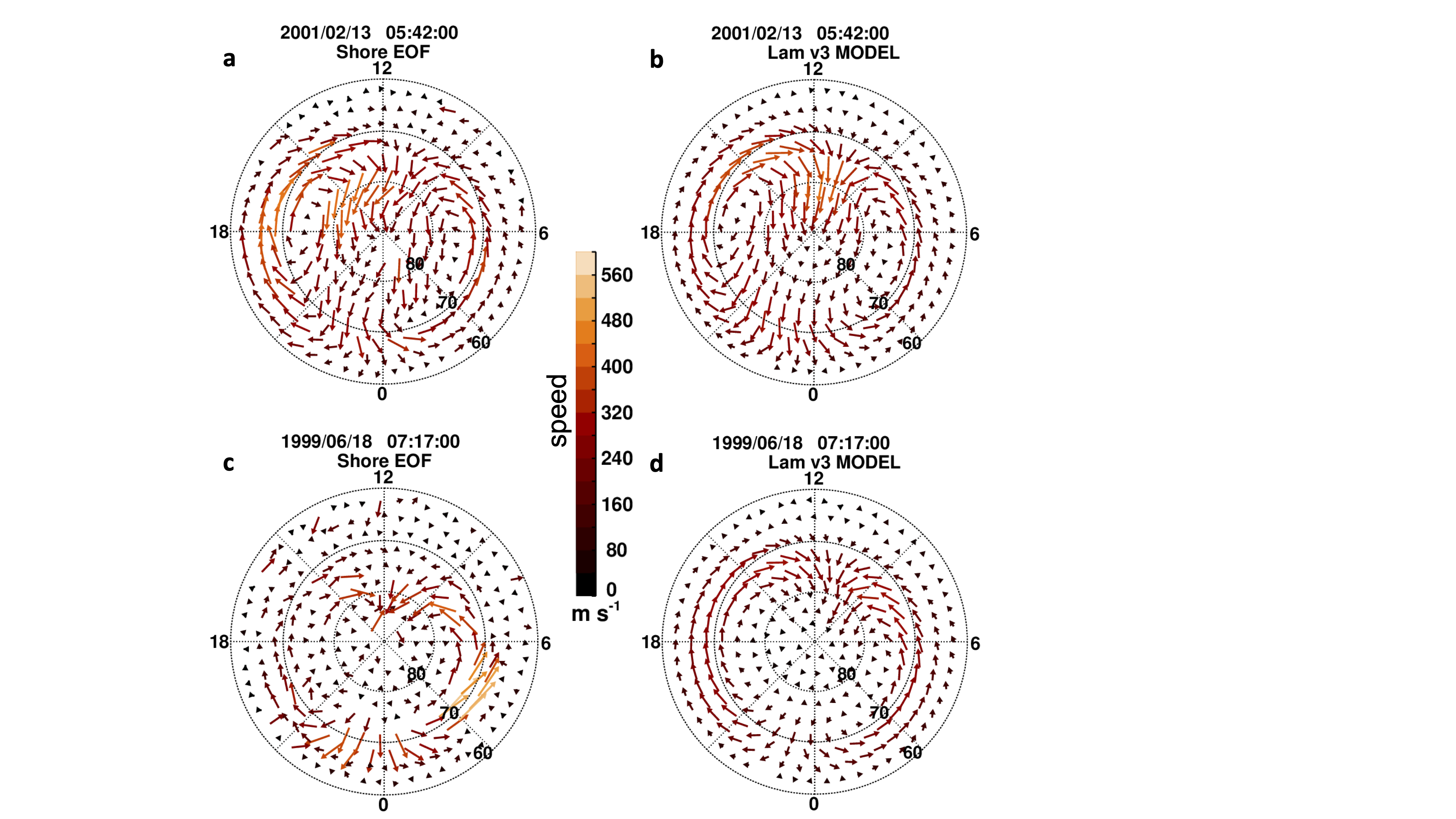

Variations in space weather in the ionized region of the Earth’s atmosphere (the ionosphere) can result in expansion of the atmosphere, increasing the atmospheric drag on objects, such as satellites, in the thermosphere. We aim to significantly improve the forecasting of the effects of atmospheric drag on satellites by more accurate modelling of space weather effects on the motion of ionized particles (plasma) in the ionosphere. We have developed a model of the variation in plasma motion using a small number of solar wind variables. The model was built using a solar cycle’s worth (1997 to 2008 inclusive) of 5-minute resolution Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) patterns derived from Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) line-of-sight observations of the plasma motion in the high-latitude northern hemisphere ionosphere (Shore et al., 2021). The model is driven by four variables: (1) the interplanetary magnetic field component By, (2) the solar wind coupling parameter epsilon, (3) a trigonometric function of the day-of-year, and (4) the monthly solar radio flux at 10.7 cm (the F10.7 index). Our model is good at reproducing the original data set - if 0 indicates that there is no reproduction and 1 indicates exact reproduction, then our model scores 0.7. Data set reproduction is best around the maximum in the solar cycle and worst at solar minimum. This is mainly due to differences in the spatiotemporal data coverage between these times but possibly also due to the model’s specification of the physical processes coupling the Sun to the Earth’s ionosphere. Our model could easily be used to forecast the ionospheric electric field about 1 hour in advance, using the real-time solar wind data available from spacecraft located upstream of the Earth.

References:

Lam, M. M., Shore, R. M., Chisham, G., Freeman, M. P., Grocott, A., Walach, M.-T., & Orr, L. (2023). A model of high latitude ionospheric convection derived from SuperDARN EOF model data. Space Weather, 21, e2023SW003428. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023SW003428

Shore, R. M., Freeman, M., Chisham, G., Lam, M. M., & Breen, P. (2022). Dominant spatial and temporal patterns of horizontal ionospheric plasma velocity variation covering the northern polar region, from 1997.0 to 2009.0 - VERSION 2.0 (Version 2.0) [Dataset]. NERC EDS UK Polar Data Centre. https://doi.org/10.5285/2b9f0e9f-34ec-4467-9e02-abc771070cd9