MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Comparative Analysis of the Various Generalized Ohm’s Law Terms in Magnetosheath Turbulence as Observed by Magnetospheric Multiscale

By Julia E. Stawarz (Imperial College London)

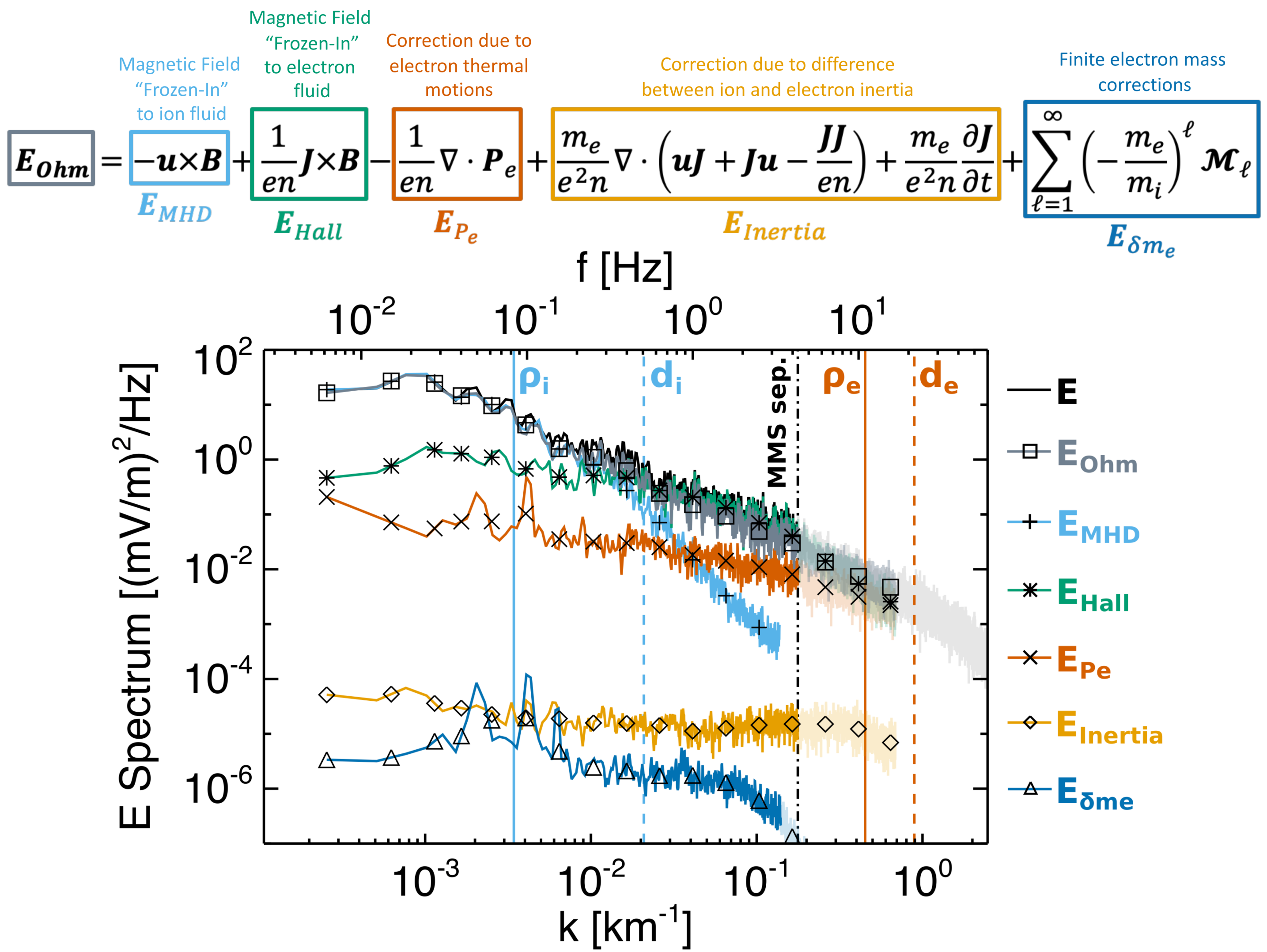

Complex, highly nonlinear, turbulent dynamics play an important role in particle acceleration and plasma heating throughout the Universe by transferring energy from large-scale to small-scale fluctuations that can be more easily dissipated. Electric fields (E) in these plasmas are responsible for mediating energy exchange between the magnetic fields and particle motions and, therefore, can provide key insight into both the nonlinear dynamics of the turbulence and the processes responsible for dissipating the fluctuations. In the collisionless plasmas often found in space, E is described by generalized Ohm’s law, displayed in Fig. 1.

In Stawarz et al. (2021), we directly measure nearly all the terms in generalized Ohm’s law for several intervals in Earth’s magnetosheath and, for the first time, examine how Ohm’s law shapes the turbulent E at different length scales. Many terms in Ohm’s law, require the computation of small-scale gradients, and, therefore, the unique high-resolution, multi-spacecraft measurements from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale mission were necessary to perform the study. As seen in Fig. 1, we find that, at scales larger than the proton inertial length, the observed E is given by the ideal magnetohydrodynamic term, while, at sub-proton scales, a combination of the Hall and electron pressure terms control E, as expected. Other terms, related to the difference between proton and electron inertia and the finite mass of electrons, remain small across the observable scales. Within the paper, we explore the interplay of the various terms in further detail by examining the correlation between the Hall and electron pressure terms, which provides insight into the types of sub-proton-scale structures formed, and by exploring the relative contribution of linear and nonlinear terms in Ohm’s law at different scales.

Fig.1: (Top) Generalized Ohm’s law for a collisionless, two species plasma, highlighting the different dynamical effects that can support E. (Bottom) Spectra of the terms in Ohm’s law and the observed E for an interval of turbulence in Earth’s magnetosheath. Vertical lines denote the proton and electron gyroradii (ρi/e), inertial lengths (di/e), and spacecraft formation size.

Please see the paper for full details:

J. E. Stawarz, L. Matteini, T. N. Parashar, L. Franci, J. P. Eastwood, C. A. Gonzalez, I. L. Gingell, J. L. Burch, R. E. Ergun, N. Ahmadi, B. L. Giles, D. J. Gershman, O. Le Contel, P.-A. Lindqvist, C. T. Russell, R. J. Strangeway, and R. B. Torbert (2021). Comparative Analysis of the Various Generalized Ohm’s Law Terms in Magnetosheath Turbulence as Observed by Magnetospheric Multiscale. J. Geophys. Res., 126, e2020JA028447, doi:10.1029/2020JA028447.

Design and Optimization of a High-Time-Resolution Magnetic Plasma Analyzer (MPA)

By Benjamin Criton (Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UCL)

Cutting-edge solar wind investigations require in-situ instruments with increasing time and energy resolution to study the important small-scale plasma processes. These processes play key roles in the overall behaviour of space plasmas. They are believed to be the origin of the heating and acceleration of the solar wind. Unfortunately, these processes happen on very short timescales. To measure them, virtually all flown plasma analyzers use an approach to select particle energies, achieved by an electric field. Faraday cups use a high-pass energy selection whilst electrostatic analysers (ESAs) a band-pass selection. This functioning requires to sweep the energy range to build the entire energy spectrum of the measured plasma. Even though Faraday cups are comparatively faster than ESAs, these two instrument categories make relatively slow measurements: 4 s for Cluster HIA, 1 s for Solar Orbiter PAS or 0.22 s for Parker Solar Probe SPC.

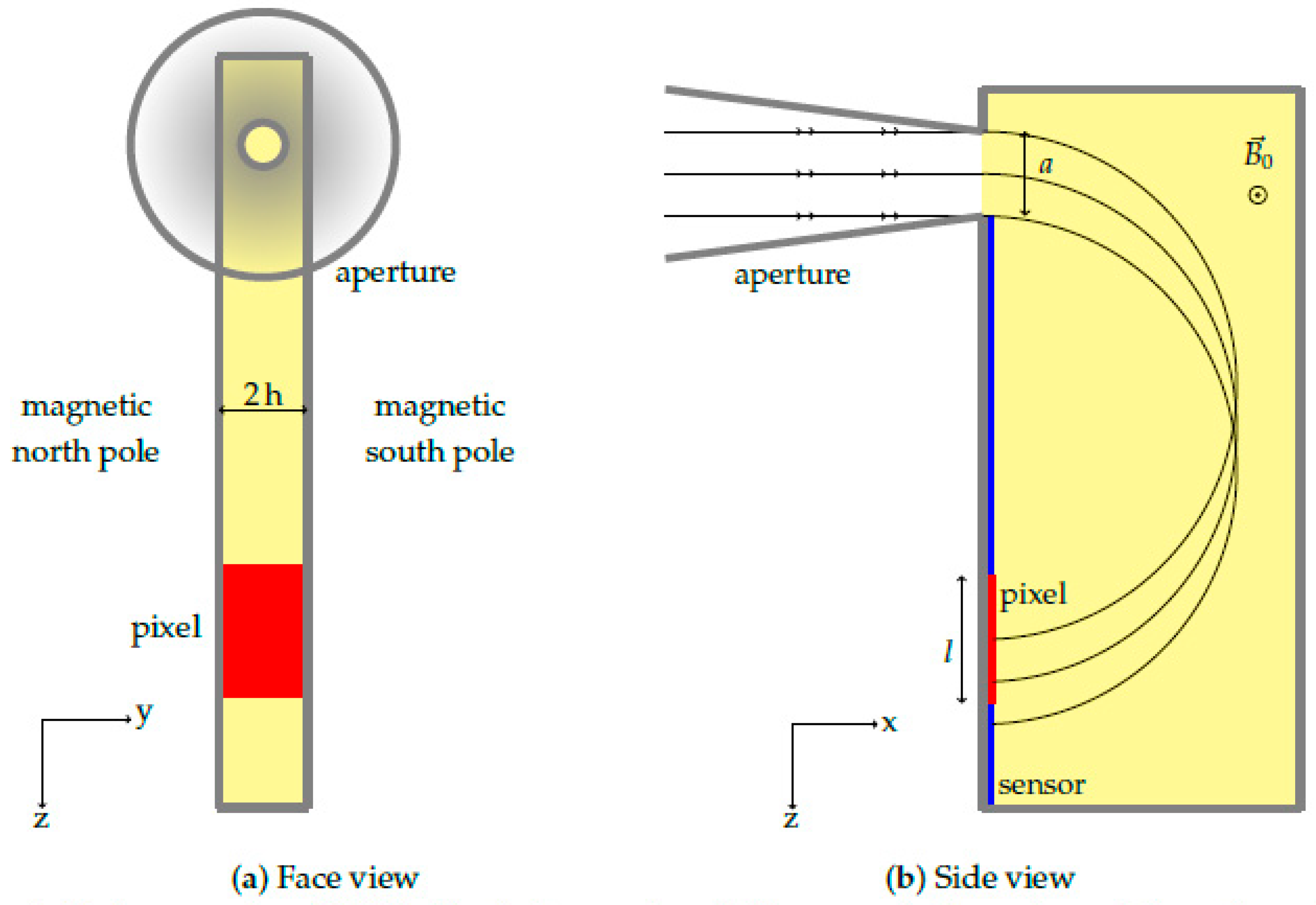

In this article, we conceptualize and design a plasma analyzer answering this rising demand for high time and energy resolution. Our new design, based on the velocity-dependent deflection of charged particles in a homogeneous magnetic field, does not require any time-dependent energy selection, making measurements much faster and reliable compared to traditional analyzers. Particles hit a position-sensitive sensor at different positions according to their velocity and mass-per-charge ratio. In one acquisition step, each incoming charged plasma particle is detected at a specific position in the sensor plane. We then translate the counts per position into an estimation of the velocity distribution function (VDF). Our study shows that this measurement principle achieves a 1D measurement of proton and alpha-particle VDFs under realistic solar wind conditions in 5 ms (200 Hz) with a velocity resolution of 2.8 %. This time cadence is two orders of magnitudes faster than the sampling frequency required to measure processes of order the proton gyro-radius at a heliocentric distance of 1 au and about 40 times faster than Parker Solar Probe SPC’s native cadence. Furthermore, the velocity/energy resolution only depends on the physical instrument parameters (aperture size, pixel size and magnetic field strength) that can be adjusted to best address the trade-off between time and energy resolution.

Fig. 1 shows the conceptual geometry of the instrument. This new instrument concept is able to unveil the fast variations of the ion VDFs in one look direction.

Please see the paper for full details:

Criton B, Nicolaou G, Verscharen D. (2020). Design and Optimization of a High-Time-Resolution Magnetic Plasma Analyzer (MPA). Applied Sciences. 10(23):8483. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238483

Evaluating the performance of a plasma analyzer for a space weather monitor mission concept

By Georgios Nicolaou (Mullard Space Science Laboratory/UCL; Southwest Research Institute)

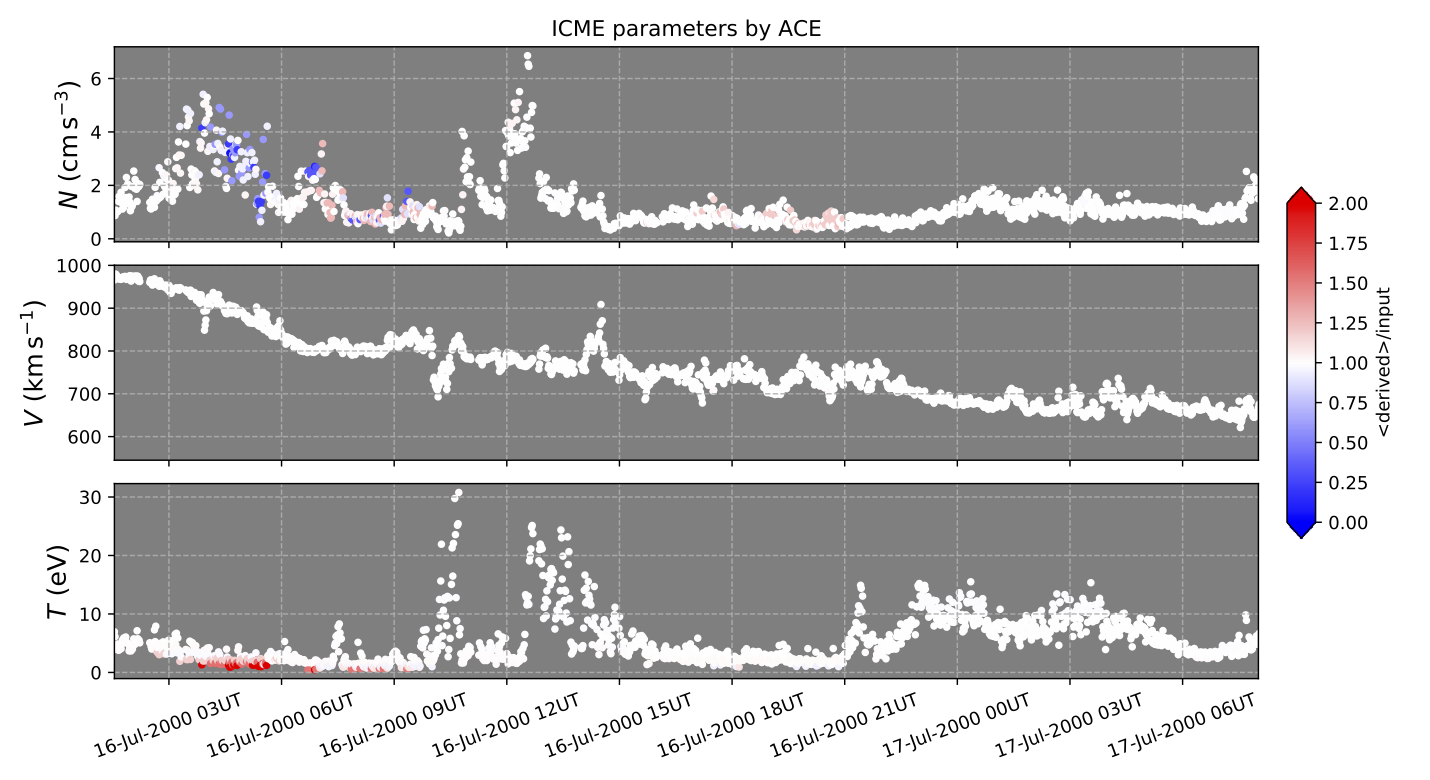

Georgios Nicolaou et al. developed a forward model of an electrostatic analyzer response which simulates observations of solar wind protons with their velocities following the classic Maxwell distribution function. This paper studies the observations of extreme space weather features such as, fast ICMEs and fast solar wind streams, but also the observations of a typical background solar wind. The model takes into account the limited sampling and resolution of the instrument. The analysis of the modeled observations derives the plasma parameters from the statistical moments of the observed velocity distribution functions. This is a classic novel analysis method, which is appropriate for space weather missions as it can be applied onboard spacecraft and predict the solar wind plasma bulk parameters very fast, reducing the required telemetry and computational resources. The comparison between the analysis results and the input parameters identifies the accuracy of the specific method applied to the observations by the instrument. The authors address the limitation of the moments analysis and demonstrate how we can overcome these limitations by fitting the observations with distribution function models. The fitting analysis is demonstrated in observations of fast ICMEs (see Figure 1) and fast solar wind streams identified in ACE observations.

Figure 1. Time series of (top) the plasma density, (middle) bulk speed, and (bottom) scalar temperature within a fast ICME recorded by ACE from 16 July 2000 01:00 to 17 July 2000 08:00. The color represents the accuracy with which the fitting analysis of the observations by our instrument derives the corresponding parameters.

Please see the paper for full details:

, , , & (2020). Evaluating the performance of a plasma analyzer for a space weather monitor mission concept. Space Weather, 18, e2020SW002559. Accepted Author Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020SW002559

The Global Distribution of Ultra‐Low‐Frequency Waves in Jupiter's Magnetosphere

By Arthur Manners (Imperial College London)

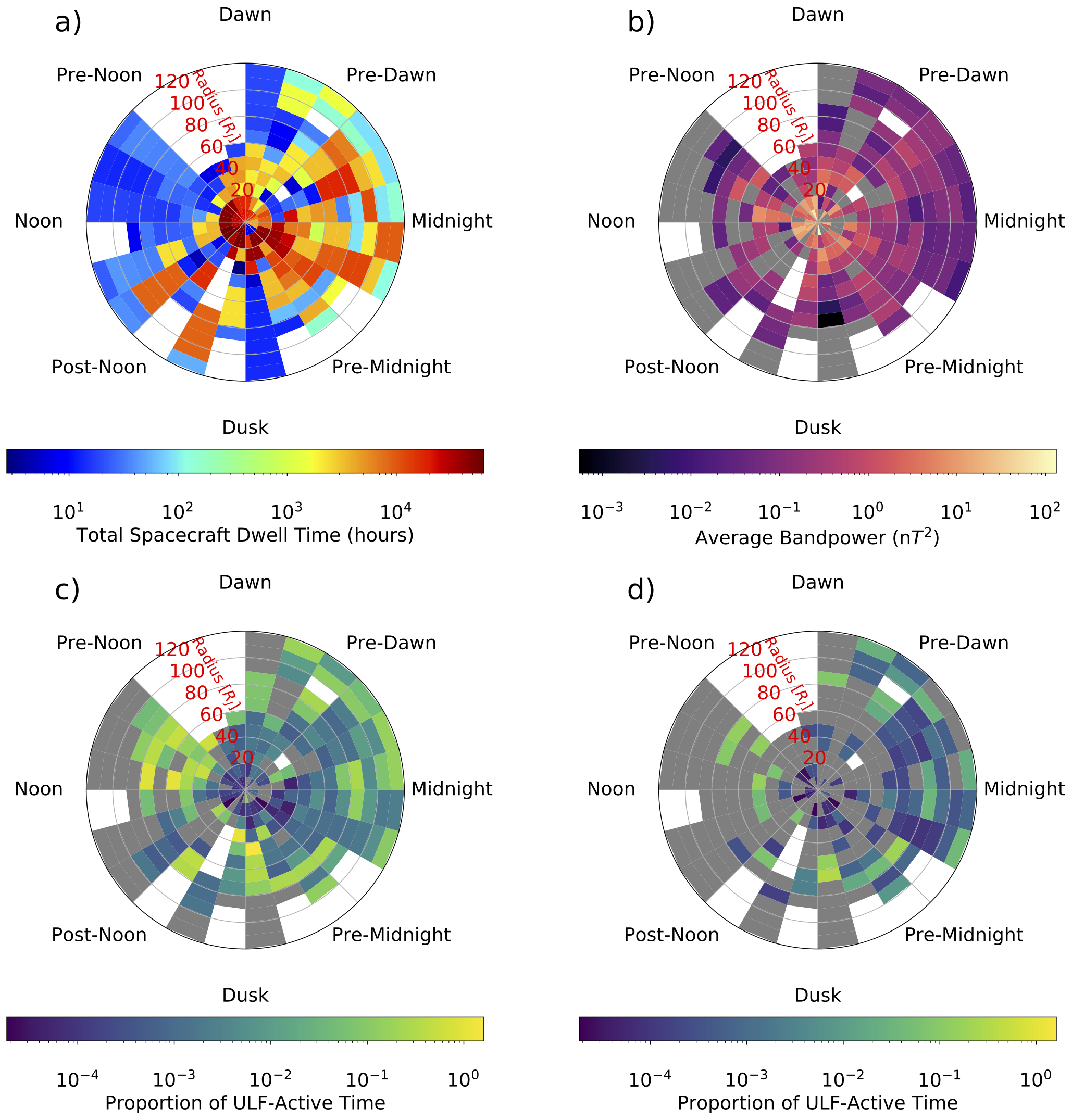

A key component to an understanding of Jupiter’s magnetosphere is how energy and momentum are transported through the system; how are perturbations communicated to regions many thousands of Earth radii distant? In the terrestrial magnetosphere, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves with frequencies in the ultra-low-frequency band (~1mHz – 1Hz) play a key role in communication throughout the system, in some cases causing the magnetospheric cavity to resonate at its natural frequencies. The Jovian magnetosphere also seems to exhibit these phenomena but limited in-situ data has prevented a fuller picture from emerging. To remedy this, we have searched the heritage magnetometer data from Galileo, Ulysses, Voyager 1 & 2 and Pioneer 10 & 11 for ULF waves. The large plasma density in the equatorial magnetodisk and comparatively rarefied high-latitude regions means the Alfvén speed is orders of magnitude lower in the disk than elsewhere, effectively confining waves to the centremost region of the magnetic field lines.

We focused our study to data where spacecraft traversed the magnetodisk and constructed a catalogue of large-amplitude ULF waves. We found several hundred events with periods spanning ~ 5 – 60 mins, with preferential periods at ~ 15 mins, ~ 30 mins and ~ 40 mins, consistent with case studies in the literature. The resultant distribution can be seen in Fig. 1. Regions close to the magnetopause at noon and along the dusk flank appear to host ULF waves most often, suggesting an external driver (Fig. 1a). However, the waves seem to be most powerful in the inner magnetosphere, close to the plasma torus, suggesting wave energy may accumulate in the region (Fig. 1b). Further study of the torus region is ongoing to further probe these findings. Overall, these results provide crucial information into large scale energy transport and pathways in Jupiter's complex magnetosphere, with significant implications for wider magnetospheric processes.

Fig. 1: An equatorial-plane projection of: (a) the total time spacecraft spent in each bin; (b) the ULF bandpower averaged over the events in each bin; (c) the proportion of time spacecraft spent in each region where significant ULF activity was observed; (d) the same as (c) but for the subset of events where only a single significant period was observed. White bins signify where there are no available data, and gray bins signify regions where spacecraft visited but observed no events.

Please see the paper for full details:

, & (2020). The global distribution of ultralow‐frequency waves in Jupiter's magnetosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2020JA028345. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA028345

Using Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Techniques to Classify Space Plasma Regimes

By Mayur R. Bakrania (MSSL, UCL)

Particle populations in collisionless space plasma environments are traditionally characterised by their moments. Distribution functions, however, provide the full picture of the state of each plasma environment. These distribution functions are not easily classified by a small number of parameters. We apply dimensionality reduction and clustering methods to particle distributions in pitch angle and energy space to distinguish between the different plasma regions. Dimensionality reduction is a specific type of unsupervised learning in which data in high-dimensional space is transformed to a meaningful representation in lower dimensional space. This transformation allows complex datasets to be characterised by analysis techniques with much higher computational efficiency. We use the following steps:

- An autoencoder to compress the data by a factor of 10 from a high-dimensional representation.

- A Principal Component Algorithm to further compress the data to a three-dimensional representation.

- The mean shift algorithm to determine how many populations are present in the data using this three-dimensional representation.

- An agglomerative clustering algorithm to assign each data-point to one of the populations.

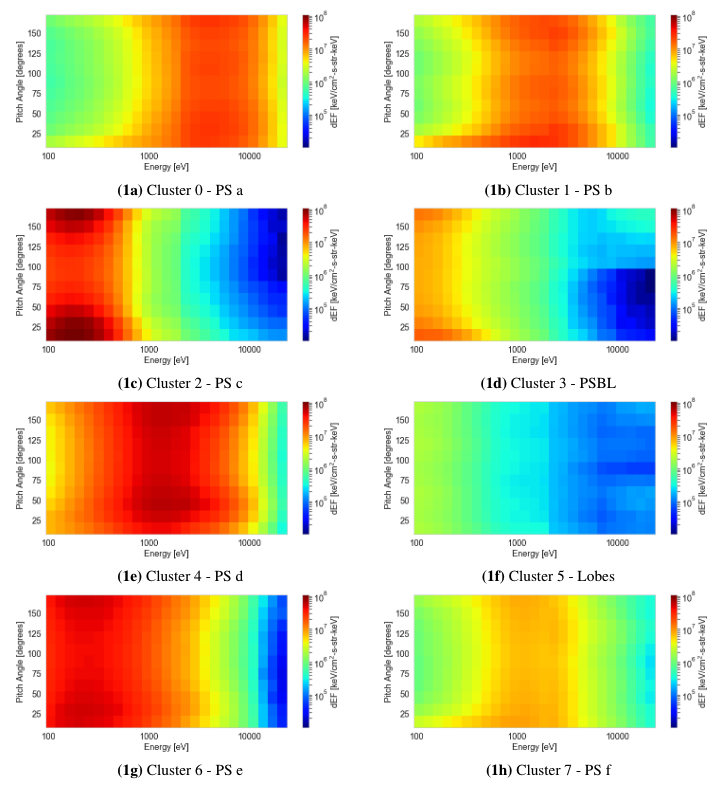

We use electron data from the magnetotail to test the effectiveness of our method. The magnetotail is traditionally divided into three different regions: the plasma sheet (PS), the plasma sheet boundary layer (PSBL), and the lobes. Starting with the ECLAT database with associated classifications based on the plasma parameters, we identify 8 distinct groups of distributions, that are dependent upon significantly more complex plasma and field dynamics. Fig. 1 shows the average electron differential energy flux distributions for each cluster. We see large differences in the average pitch angle/energy distributions. Each distribution differs by the: peak flux energy, peak flux value, or the pitch angle anisotropy. The lack of identical distributions shows mean shift has not overestimated the number of clusters. This novel technique reveals new information on the physical processes shaping magnetotail electron distributions, and has significant implications for analysing a wide range of plasma regimes.

Fig. 1: Average electron differential energy flux distributions as a function of pitch angle and energy for each of the eight clusters (A–H) classified by the agglomerative clustering algorithm. Each cluster is assigned a magnetotail region (included in the sub-captions) based on our interpretation of their plasma and magnetic field parameters.

Please see the paper for full details:

M. R. Bakrania, Rae I. J., Walsh A. P., Verscharen D. and Smith A. W. (2020). Using Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Techniques to Classify Space Plasma Regimes. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 7:593516. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2020.593516