MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Observations of closed magnetic flux embedded in the lobes during periods of northward IMF

By Laura Fryer (University of Southampton)

The coupling between the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) and the magnetosphere has been extensively studied over the last few decades. This has been facilitated by the launch of multiple spacecraft, such as ESA’s Cluster mission (Escoubet et al 2001), which probes different regions of the Earth's magnetosphere. There have been many studies dedicated to understanding the response of the magnetosphere during more turbulent southward orientated IMF conditions, however, there is still great uncertainty in our understanding of how the magnetosphere, particularly the magnetotail, responds to northward IMF. In general, the lobes in the Earth's magnetotail are typically described as having cool, low energy and often low density plasma populations and therefore hot plasma observations are unexpected in these regions of the magnetosphere. Despite this, there have been a small number of studies reporting energetic plasma populations in the lobes during northward IMF conditions (Huang et al 1987, Shi et al 2013, Fear et al 2014).

We present three case studies which show hot plasma embedded in the lobes of the magnetosphere. For two of these case studies, simultaneous observations of the plasma sheet confirmed that the energies observed within the lobe were directly comparable in magnitude to the populations in the plasma sheet. In addition to this, we observed plasma characteristics which indicated that the plasma is likely to be on closed field lines (evidenced by electron pitch angle distributions and variation in motion of the spacecraft). Tracing the footprint of these field lines to ionospheric altitudes revealed that in each Event, the footprint intersected with a transpolar arc. An example of this for Event 2 can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the footprint of each of the Cluster spacecraft in the tetrahedron, intersecting with a transpolar arc. This provided further evidence to suggest that the energetic plasma was likely to form on closed field lines and could be explained well by the result of recent magnetotail reconnection during northward IMF conditions, a mechanism proposed by Milan et al 2005 to explain the formation of transpolar arcs.

Figure 1: SSUSI (DMSP-F16) FUV auroral observations from the Northern Hemisphere. The panels show the images taken from 16:06 UT to 19:28 UT for Event 2. The data is plotted in AACGM coordinates (magnetic latitude, MLT). The top three images are repeated in the bot-tom row but overplotted with the footprints of Cluster 1, 2, 3 and 4. This has been traced using the T96 model (Tsyganenko, 1996) to an altitude of 120km and are represented by black, red, green and blue circles respectively.

Please see the paper for full details:

Fryer, L. J., Fear, R. C., Coxon, J. C., & Gingell, I. L. (2021). Observations of closed magnetic flux embedded in the lobes during periods of northward IMF. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 126, e2021JA029281. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JA029281

Average Ionospheric Electric Field Morphologies During Geomagnetic Storm Phases

By Maria-Theresia Walach (Lancaster University)

Geomagnetic storms are a global electrodynamic phenomenon, during which the ring current is loaded with energy. The coupled magnetospheric/ionospheric system responds during a geomagnetic storm and the dynamics of the system can be monitored using measurements of the high-latitude ionosphere. Ordering data from the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) by geomagnetic storm phase, we produce convection maps for a geomagnetic storm, which allow us to discern changes that occur in association with the development of the storm phases. We utilize principal component analysis to identify and quantify the primary electric potential morphologies during geomagnetic storms. Along with information on the size of the patterns, the first six eigenvectors provide over ∼80% of the variability in the morphology, providing us with a robust analysis tool to quantify the main changes in the patterns. Studying the first six eigenvectors and their eigenvalues shows that the primary changes in the morphologies with respect to storm phase are the convection potential enhancing and the dayside throat rotating from pointing toward the early afternoon sector to being more sunward aligned during the main phase of the storm. We find that the ionospheric electric potential increases through the main phase and then decreases once the recovery phase begins. Furthermore, we find that a two‐cell convection pattern is dominant throughout and that the dusk cell is overall stronger than the dawn cell.

The figure shows the mean electrostatic potential, followed by the first six eigenvectors. These show the most common components that can be used to make up the ionospheric convection patterns during geomagnetic storms.

Figure Caption: Ionospheric electric field component patterns showing the mean for geomagnetic storms (top left), followed by the patterns corresponding to the first six eigenvectors of the Principal Component Analysis. Each pattern is centered on the geomagnetic pole, with 12:00 magnetic local time pointing toward the top of the page, and dusk toward the left. Lines of geomagnetic latitudes are indicated from 40° to 90° by the dashed gray circles.

Animation Caption: Average convection patterns from SuperDARN data for geomagnetic storm main phase

Please see the paper for full details: Walach, M.‐T., Grocott, A., & Milan, S. E. (2021). Average ionospheric electric field morphologies during geomagnetic storm phases. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 126, e2020JA028512. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA028512

Network community structure of substorms using SuperMAG magnetometers

By Lauren Orr (University of Warwick)

Geomagnetic substorms are a global magnetospheric reconfiguration, during which energy is abruptly transported to the ionosphere. Central to this are the auroral electrojets, large-scale ionospheric currents that are part of a larger three-dimensional system, the substorm current wedge. Many, often conflicting, magnetospheric reconfiguration scenarios have been proposed to describe the substorm current wedge evolution and structure. We have used well-established network science techniques to analyze data from >100 ground-based magnetometers operated by the SuperMAG collaboration1. We translated this data into a time-varying directed network, based on canonical cross-correlation of the vector magnetic field perturbations measured at each magnetometer pair2,3 and performed community detection on the network4. Communities are locally dense but globally sparse groups of connections in the network, identifying emerging coherent patterns in the current system as the substorm evolves. Analysis of 41 substorms exhibit robust structural change from many small, uncorrelated current systems before substorm onset, to a large spatially-extended coherent system, between 10-20 minutes after onset. We interpret this as strong indication that the auroral electrojet system during substorm expansions is inherently a large-scale phenomenon and is not solely due to many meso-scale wedgelets.

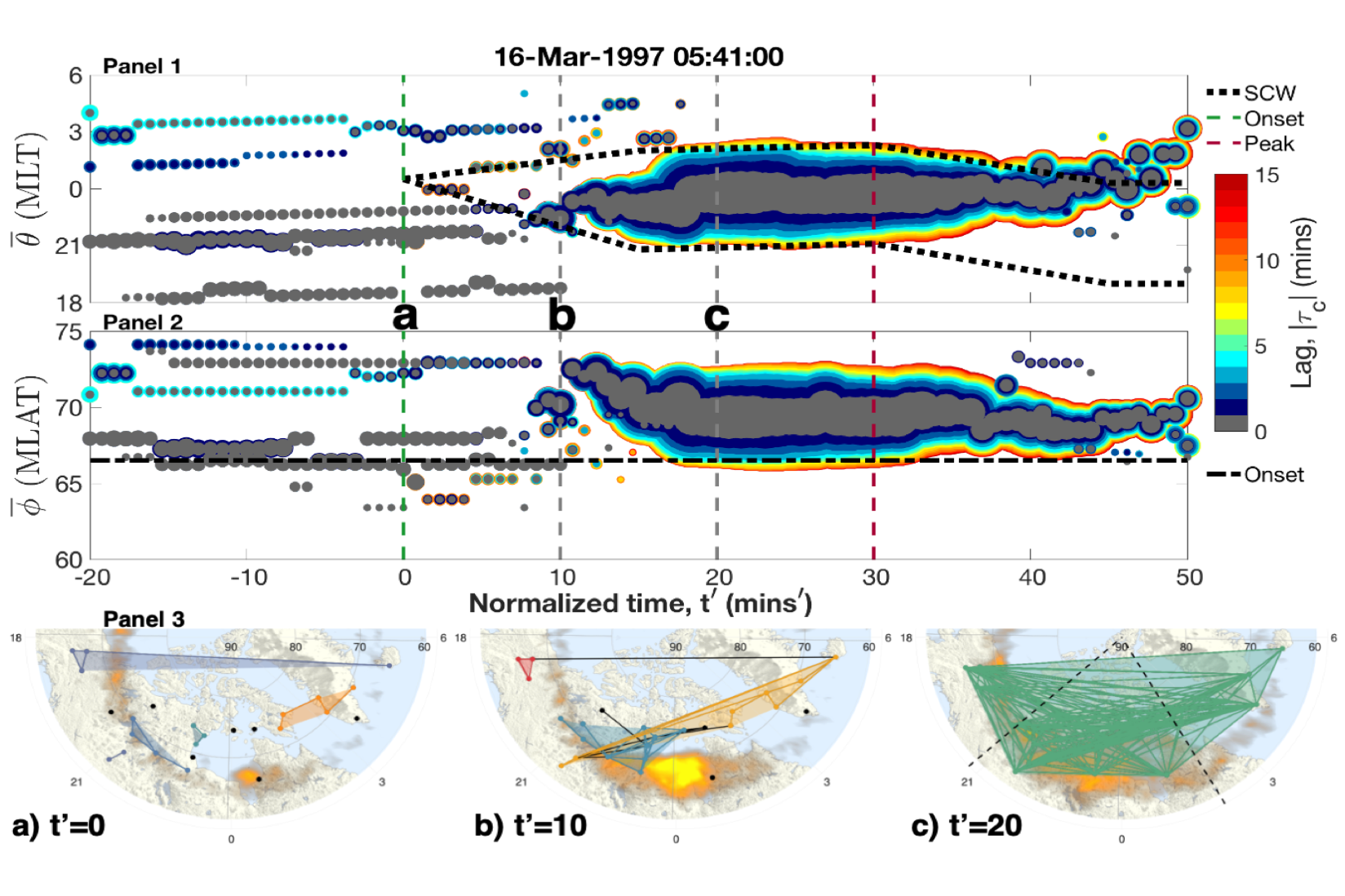

Figure 1: The community structure of a substorm on the 16/03/1997. The abscissa of all panels is normalized time, where t'=0 is onset (dashed green line) and t'=30 (dashed purple line) is the time of maximum auroral bulge expansion. Panels 1-2 plots individual communities as circles where the size of the circle reflects the number of connections within the community. The ordinate plots the mean MLT/MLAT of the community, and the color indicates the proportion of connections with each time lag, |τc|. The dashed lines overplotted are the edges of the auroral bulge (MLT) and the onset location (MLAT), found from auroral images. Panel 3 shows snapshots of the community structure at time points t’=0 (onset), t’=10 and t’=20, overplotted on maps provided by SuperMAG1. There is a clear shift from many, small uncorrelated communities before onset to one large correlated system half way through the expansion phase.

Please see the paper for full details:

Orr, L., Chapman, S.C., Gjerloev, J.W. et al. Network community structure of substorms using SuperMAG magnetometers. Nat Commun 12, 1842 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22112-4

The Cushion Region and Dayside Magnetodisc Structure at Saturn

By Ned Staniland (Imperial College London)

The moons Enceladus and Io are internal plasma sources for the magnetospheres of Saturn and Jupiter, respectively. This, coupled with their rapid rotation rates (~10 h), radially stretches the magnetic field from a dipole to a magnetodisc. However, this structure can break down at large distances where the magnetic field can no longer contain the equatorial plasma. This quasi-dipolar layer between the current sheet outer edge and magnetopause is known as the “cushion region.” This has previously been observed at Jupiter, predominantly at dawn, but not at Saturn (Went et al., 2011). It is suggested to be populated by mass-depleted flux tubes following magnetotail reconnection.

We present the first evidence of a cushion region forming at Saturn. From the complete Cassini orbital dataset, only five examples are identified, showing this phenomenon to be rare, with four at local time dusk and one pre‐noon. The dusk cushion observed could be due to asymmetric heating of plasma in the Saturn system (Kaminker et al., 2017), as well as the changing magnetic field configuration through dusk where the field is less confined by the magnetopause, resulting in disc instabilities (Kivelson and Southwood, 2005).

These results highlight a key difference between the rotationally driven magnetospheres of Saturn and Jupiter. The rare cushion region examples found and evidence of patchy reconnection at Saturn (Delamere et al., 2015) compared to the persistent cushion region at Jupiter (Went et al., 2011) and statistical x-line across the Jovian tail (Vogt et al., 2010) shows that the mass transport and loss mechanisms differ between these systems. Whilst the Saturn system is often described as being between Jupiter and the Earth in terms of dynamics and structure, these results suggest that this is perhaps an oversimplified description.

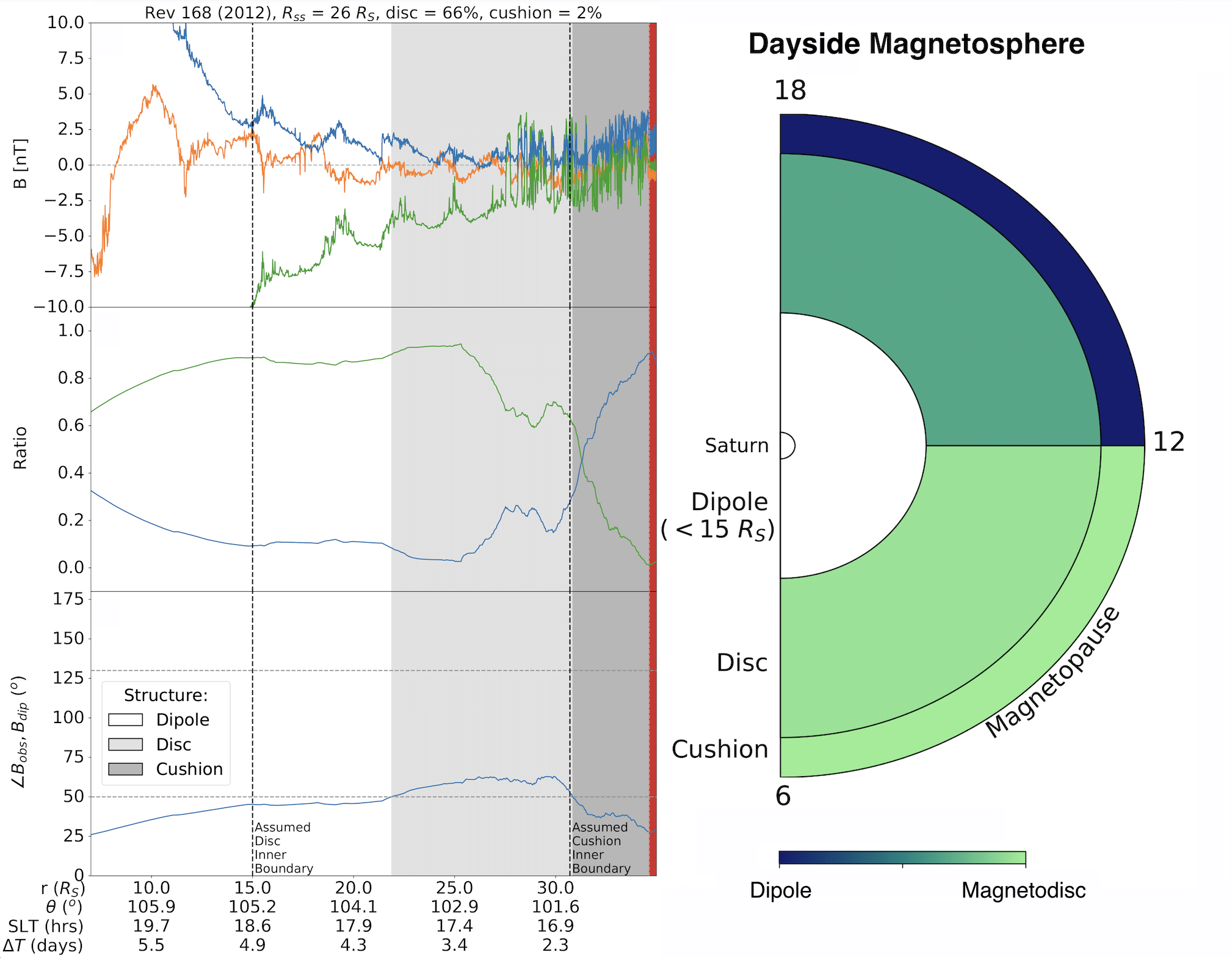

Figure: The left plot shows an example of a cushion region at Saturn. The top panel shows magnetic field data. The second panel showing the relative contributions of the radial (green) and meridional (blue) components to the total field. The third panel shows the angle between the observed field and a dipole. For this example, the field is disc-like in the middle magnetosphere, but the structure breaks down in the outer magnetosphere (highlighted by the background colours). The right plot shows the average dayside magnetic field configuration. The field is more disc-like in the dawn sector whilst there is a quasi-dipolar region in the outer magnetosphere at dusk.

Please see the full paper for details:

, , , & (2021). The cushion region and dayside magnetodisc structure at Saturn. Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2020GL091796. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL091796

Particle-In-Cell Simulations of the Cassini Spacecraft's Interaction with Saturn's Ionosphere during the Grand Finale

By Zeqi Zhang (Imperial College London)

Cassini's Grand Finale at Saturn was the first time the giant planet’s atmosphere had been sampled in-situ. The ionosphere, and indeed the Saturn system as a whole, provided a uniquely different environment compared to the terrestrial planets and also Jupiter, with populations of charged dust grains influencing the plasma dynamics. When passing through Saturn’s ionosphere, Cassini observed an ionosphere dominated by ice and dust particles which continually rain inward from Saturn’s vast ring system and soak up free electrons, thus producing a dusty complex plasma. Understanding how incident plasma currents charge a spacecraft relative to its surrounding environment is important for interpreting the surrounding plasma conditions and on-board plasma measurements. In this article, we describe three dimensional Particle-In-Cell simulations of the Cassini spacecraft’s interaction with plasmas representative of Saturn's ionosphere during the Grand Finale.

The global simulations revealed complex interaction features such as a highly structured wake containing spacecraft-scale vortices and electron wings, a Langmuir wave analogue of Alfvén wings, which propagated at small angles to the magnetic field and upstream into the pristine plasma ahead of Cassini. The results explain how a large negatively charged plasma component combined with a large negative to positive ion mass ratio is able to drive the spacecraft to the observed positive potentials, a previously unexplained phenomenon observed during end-of-mission. Despite the high electron depletions, the electron properties are found as a significant controlling factor for the spacecraft potential together with the magnetic field orientation which induces a potential gradient directed across Cassini's asymmetric body. This study reveals the global spacecraft interaction experienced by Cassini during the Grand Finale in a plasma environment dominated by a class of physics quite different to those considered in the classical view of spacecraft charging.

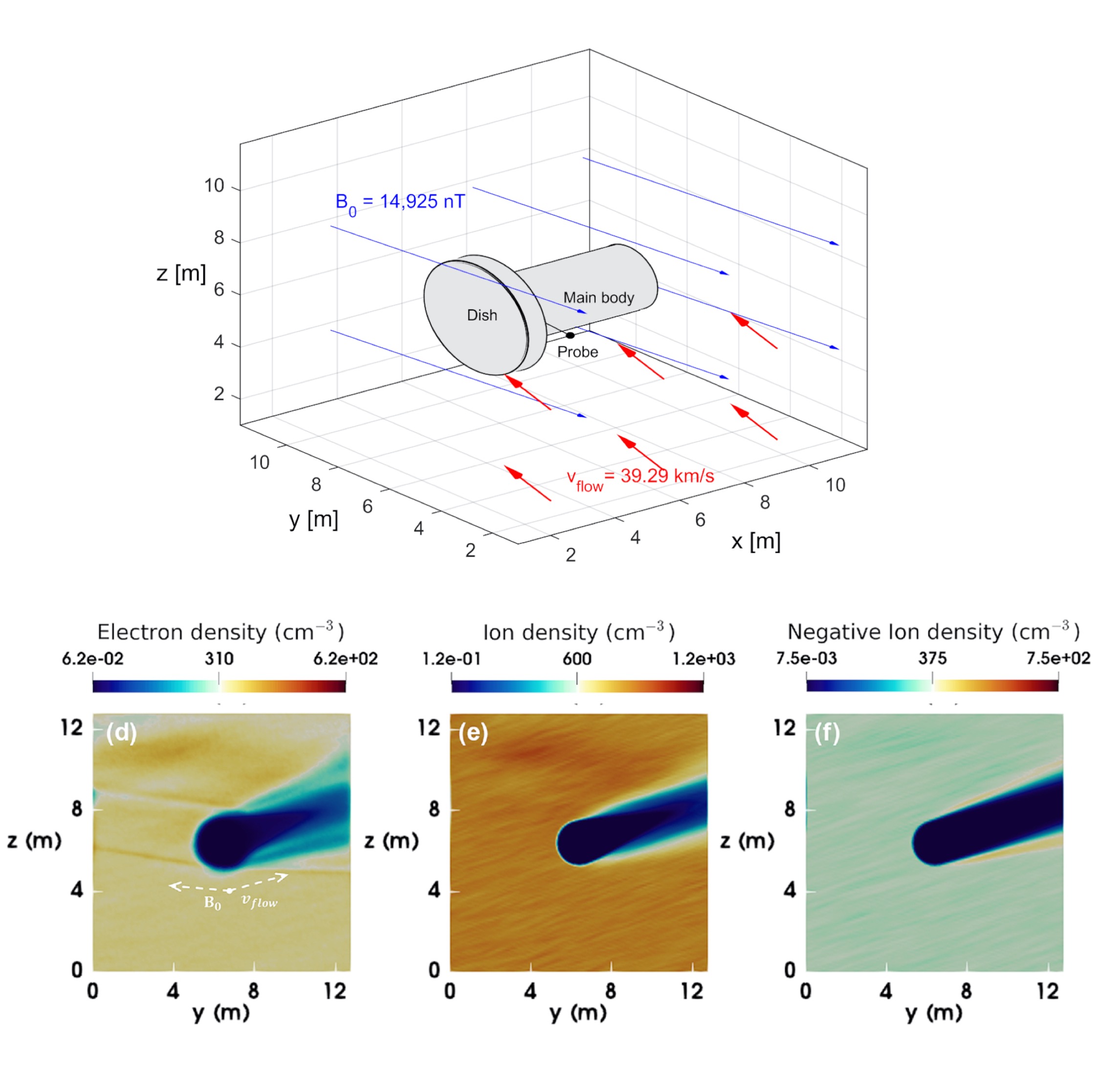

Figure 1. The upper schematic shows the simulation configuration for Cassini during Grand Finale Rev 292 ingress at 2500 km Saturn altitude. The lower panels shows the electron (left-hand panel), ion (centre panel) and negative ion (right-hand panel) densities in the Y-Z plane through Cassini’s main body. The plasma wake is longer for the larger species and electron wing structures are visible in the electron density which propagate at small angles to the ambient magnetic field.

Please see the paper for full details:

Zhang, Z., Desai, R.T., Miyake, Y., Usui, H., Shebanits, O., (2021). Particle-In-Cell Simulations of the Cassini Spacecraft’s Interaction with Saturn’s Ionosphere during the Grand Finale. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 504, Issue 1, pp 964 - 973, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab750.