MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Network community structure of substorms using SuperMAG magnetometers

By Lauren Orr (University of Warwick)

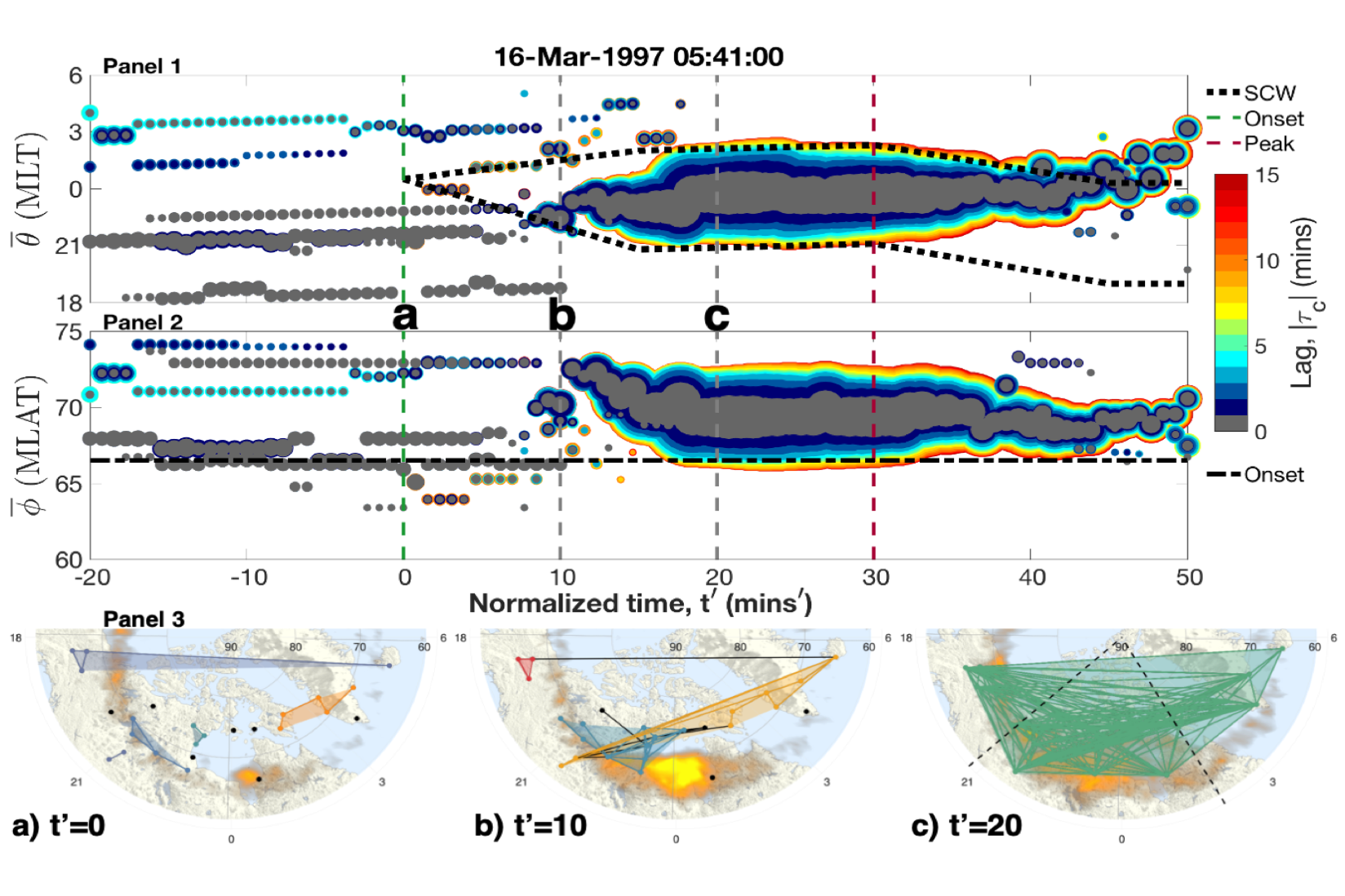

Geomagnetic substorms are a global magnetospheric reconfiguration, during which energy is abruptly transported to the ionosphere. Central to this are the auroral electrojets, large-scale ionospheric currents that are part of a larger three-dimensional system, the substorm current wedge. Many, often conflicting, magnetospheric reconfiguration scenarios have been proposed to describe the substorm current wedge evolution and structure. We have used well-established network science techniques to analyze data from >100 ground-based magnetometers operated by the SuperMAG collaboration1. We translated this data into a time-varying directed network, based on canonical cross-correlation of the vector magnetic field perturbations measured at each magnetometer pair2,3 and performed community detection on the network4. Communities are locally dense but globally sparse groups of connections in the network, identifying emerging coherent patterns in the current system as the substorm evolves. Analysis of 41 substorms exhibit robust structural change from many small, uncorrelated current systems before substorm onset, to a large spatially-extended coherent system, between 10-20 minutes after onset. We interpret this as strong indication that the auroral electrojet system during substorm expansions is inherently a large-scale phenomenon and is not solely due to many meso-scale wedgelets.

Figure 1: The community structure of a substorm on the 16/03/1997. The abscissa of all panels is normalized time, where t'=0 is onset (dashed green line) and t'=30 (dashed purple line) is the time of maximum auroral bulge expansion. Panels 1-2 plots individual communities as circles where the size of the circle reflects the number of connections within the community. The ordinate plots the mean MLT/MLAT of the community, and the color indicates the proportion of connections with each time lag, |τc|. The dashed lines overplotted are the edges of the auroral bulge (MLT) and the onset location (MLAT), found from auroral images. Panel 3 shows snapshots of the community structure at time points t’=0 (onset), t’=10 and t’=20, overplotted on maps provided by SuperMAG1. There is a clear shift from many, small uncorrelated communities before onset to one large correlated system half way through the expansion phase.

Please see the paper for full details:

Orr, L., Chapman, S.C., Gjerloev, J.W. et al. Network community structure of substorms using SuperMAG magnetometers. Nat Commun 12, 1842 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22112-4

The Cushion Region and Dayside Magnetodisc Structure at Saturn

By Ned Staniland (Imperial College London)

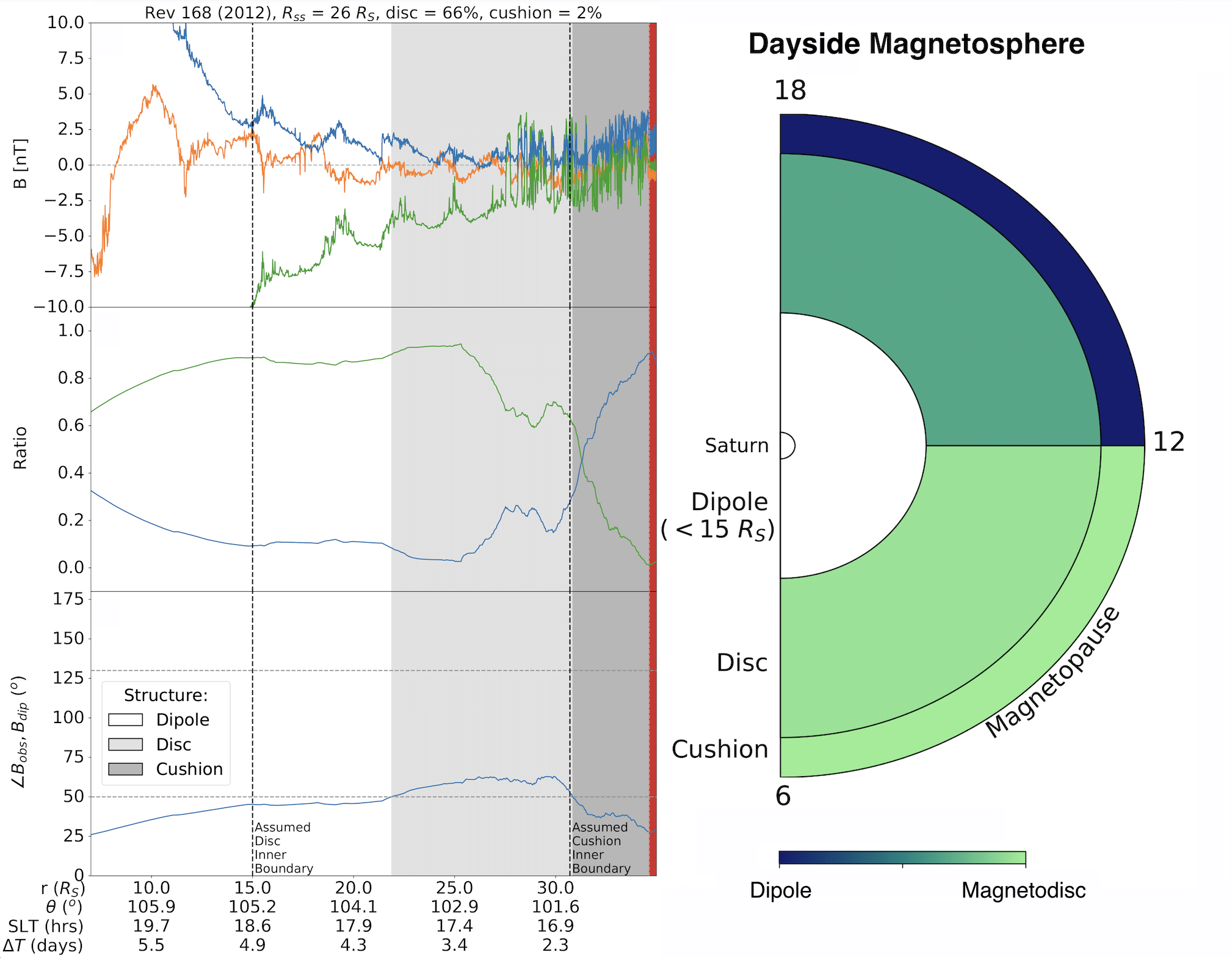

The moons Enceladus and Io are internal plasma sources for the magnetospheres of Saturn and Jupiter, respectively. This, coupled with their rapid rotation rates (~10 h), radially stretches the magnetic field from a dipole to a magnetodisc. However, this structure can break down at large distances where the magnetic field can no longer contain the equatorial plasma. This quasi-dipolar layer between the current sheet outer edge and magnetopause is known as the “cushion region.” This has previously been observed at Jupiter, predominantly at dawn, but not at Saturn (Went et al., 2011). It is suggested to be populated by mass-depleted flux tubes following magnetotail reconnection.

We present the first evidence of a cushion region forming at Saturn. From the complete Cassini orbital dataset, only five examples are identified, showing this phenomenon to be rare, with four at local time dusk and one pre‐noon. The dusk cushion observed could be due to asymmetric heating of plasma in the Saturn system (Kaminker et al., 2017), as well as the changing magnetic field configuration through dusk where the field is less confined by the magnetopause, resulting in disc instabilities (Kivelson and Southwood, 2005).

These results highlight a key difference between the rotationally driven magnetospheres of Saturn and Jupiter. The rare cushion region examples found and evidence of patchy reconnection at Saturn (Delamere et al., 2015) compared to the persistent cushion region at Jupiter (Went et al., 2011) and statistical x-line across the Jovian tail (Vogt et al., 2010) shows that the mass transport and loss mechanisms differ between these systems. Whilst the Saturn system is often described as being between Jupiter and the Earth in terms of dynamics and structure, these results suggest that this is perhaps an oversimplified description.

Figure: The left plot shows an example of a cushion region at Saturn. The top panel shows magnetic field data. The second panel showing the relative contributions of the radial (green) and meridional (blue) components to the total field. The third panel shows the angle between the observed field and a dipole. For this example, the field is disc-like in the middle magnetosphere, but the structure breaks down in the outer magnetosphere (highlighted by the background colours). The right plot shows the average dayside magnetic field configuration. The field is more disc-like in the dawn sector whilst there is a quasi-dipolar region in the outer magnetosphere at dusk.

Please see the full paper for details:

, , , & (2021). The cushion region and dayside magnetodisc structure at Saturn. Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2020GL091796. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL091796

Particle-In-Cell Simulations of the Cassini Spacecraft's Interaction with Saturn's Ionosphere during the Grand Finale

By Zeqi Zhang (Imperial College London)

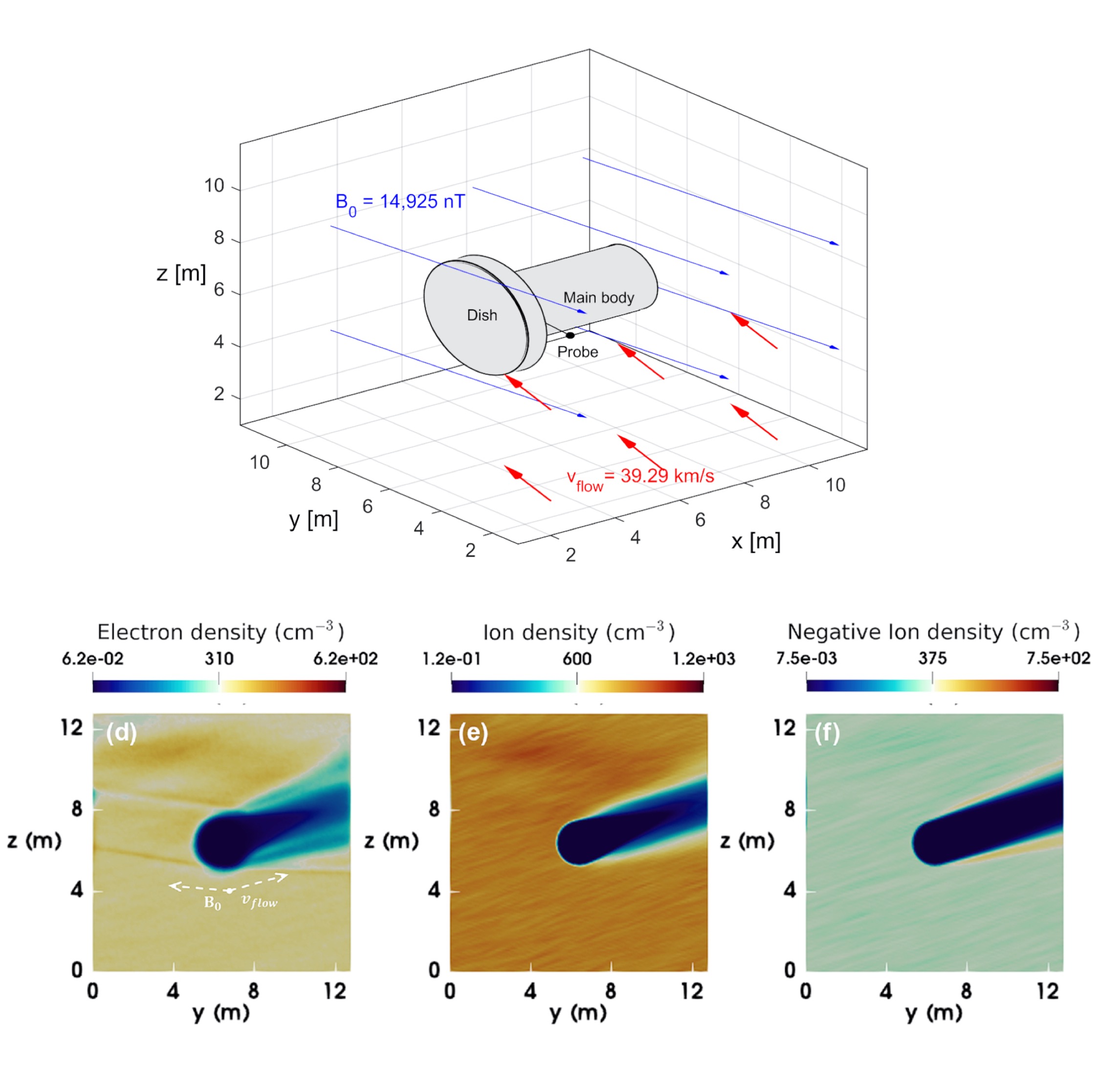

Cassini's Grand Finale at Saturn was the first time the giant planet’s atmosphere had been sampled in-situ. The ionosphere, and indeed the Saturn system as a whole, provided a uniquely different environment compared to the terrestrial planets and also Jupiter, with populations of charged dust grains influencing the plasma dynamics. When passing through Saturn’s ionosphere, Cassini observed an ionosphere dominated by ice and dust particles which continually rain inward from Saturn’s vast ring system and soak up free electrons, thus producing a dusty complex plasma. Understanding how incident plasma currents charge a spacecraft relative to its surrounding environment is important for interpreting the surrounding plasma conditions and on-board plasma measurements. In this article, we describe three dimensional Particle-In-Cell simulations of the Cassini spacecraft’s interaction with plasmas representative of Saturn's ionosphere during the Grand Finale.

The global simulations revealed complex interaction features such as a highly structured wake containing spacecraft-scale vortices and electron wings, a Langmuir wave analogue of Alfvén wings, which propagated at small angles to the magnetic field and upstream into the pristine plasma ahead of Cassini. The results explain how a large negatively charged plasma component combined with a large negative to positive ion mass ratio is able to drive the spacecraft to the observed positive potentials, a previously unexplained phenomenon observed during end-of-mission. Despite the high electron depletions, the electron properties are found as a significant controlling factor for the spacecraft potential together with the magnetic field orientation which induces a potential gradient directed across Cassini's asymmetric body. This study reveals the global spacecraft interaction experienced by Cassini during the Grand Finale in a plasma environment dominated by a class of physics quite different to those considered in the classical view of spacecraft charging.

Figure 1. The upper schematic shows the simulation configuration for Cassini during Grand Finale Rev 292 ingress at 2500 km Saturn altitude. The lower panels shows the electron (left-hand panel), ion (centre panel) and negative ion (right-hand panel) densities in the Y-Z plane through Cassini’s main body. The plasma wake is longer for the larger species and electron wing structures are visible in the electron density which propagate at small angles to the ambient magnetic field.

Please see the paper for full details:

Zhang, Z., Desai, R.T., Miyake, Y., Usui, H., Shebanits, O., (2021). Particle-In-Cell Simulations of the Cassini Spacecraft’s Interaction with Saturn’s Ionosphere during the Grand Finale. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 504, Issue 1, pp 964 - 973, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab750.

Magnetic topology of actively evolving and passively convecting structures in the turbulent solar wind

By Bogdan Hnat (University of Warwick)

Plasma turbulence and magnetic reconnection are fundamental to the transfer of energy and momentum between field and flow and are ubiquitous in laboratory and in space plasmas. Both processes generate coherent structures, which modify the energy transfer between different scales. The precise energy balance depends on the relative prevalence of specific topological structures, their rate of evolution and their ability to carry currents.

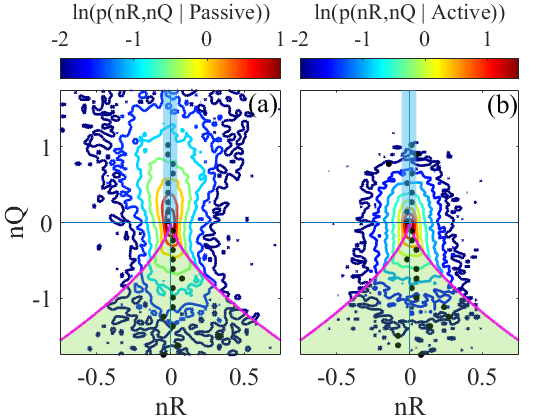

Multi-point satellite observations of the high Mach number solar wind offer a unique opportunity to directly probe the properties of the coherent structures inherent in plasma turbulence and reconnection. We use topological invariants, nQ and nR, of the magnetic field gradient tensor to classify the topology of magnetic structures and to quantify the prevalence of actively evolving and passively advective structures and their contribution to Ohmic heating. We established that at least 25% of all samples are passively advected by the solar wind. The passive structures are dominated by plasmoids which carry a significant current density. Actively evolving structures are primarily quasi-2D flux ropes and 3D X-points. Magnetic configurations that actively evolve and carry a significant current, give a lower bound on the fraction of structures that can dissipate and heat the plasma to be ~35% of the total population. These are dominated by quasi-2D flux rope topology. Magnetic X-points constitute ~40% of all evolving structures, but only 1/5 of these carry a significant current.

Figure 1. Conditional joint probability density for (a) force-free magnetic field, passively advecting configurations; (b) actively evolving magnetic structures. Rectangular blue shaded region with nQ>0 corresponds to quasi-2D flux ropes (O-points). Green shaded region, nQ<0 corresponds to hyperbolic 3D X-point magnetic topologies and unshaded regions represent plasmoids. Magenta line separates regions of hyperbolic and elliptic magnetic field lines.

Please see the paper for full details:

Hnat, B., Chapman, S. C., & Watkins, N. W. (2021). Magnetic Topology of Actively Evolving and Passively Convecting Structures in the Turbulent Solar Wind, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 125101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.125101

Electron Bulk Heating At Saturn’s Magnetopause

By Matthew Cheng (University College London)

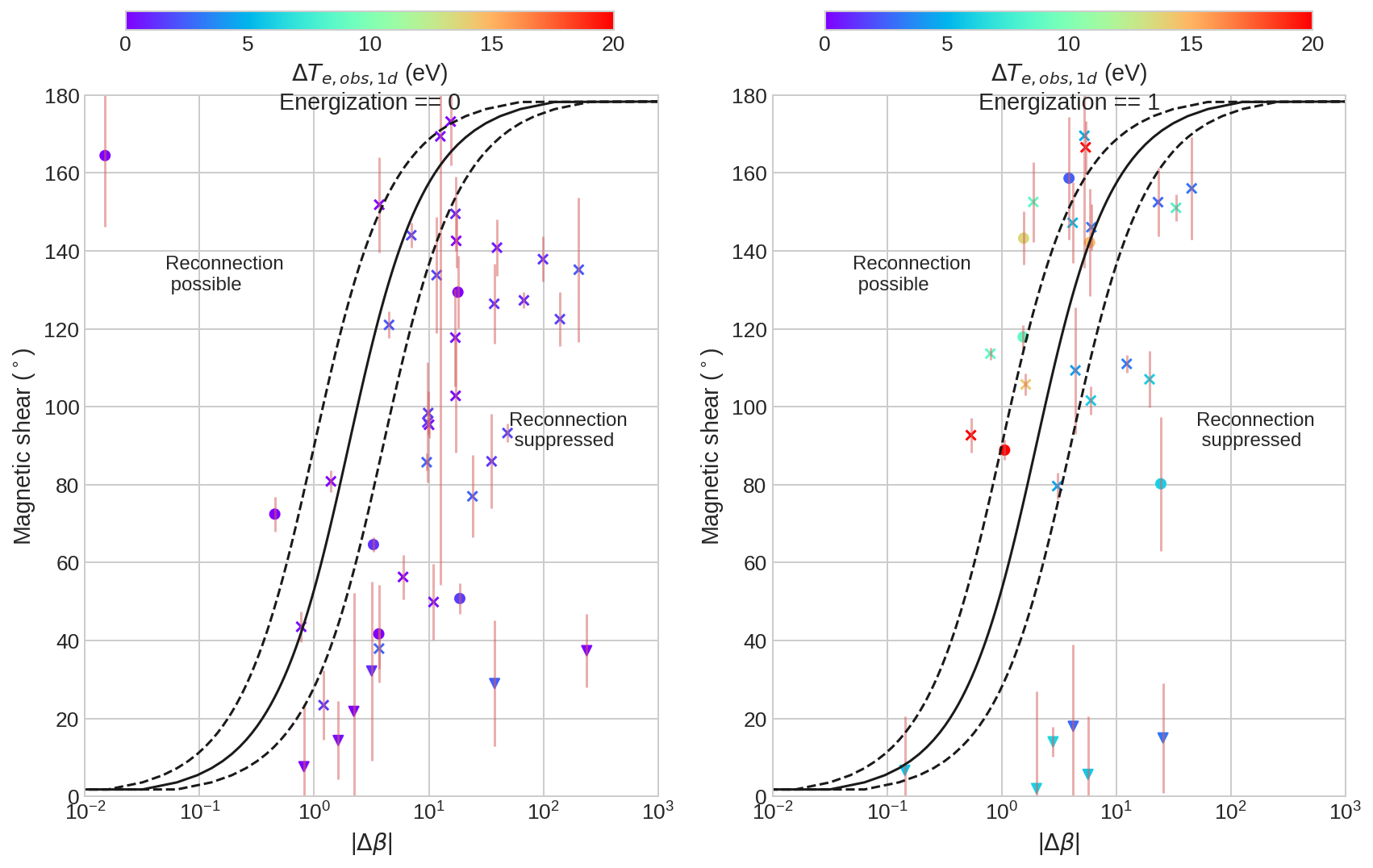

The magnetopause (MP) boundary is formed by the solar wind plasma flow interacting with a planetary magnetic field. Magnetic reconnection is an important process at this boundary as it energises plasma via release of magnetic energy. This process can lead to an “open” magnetosphere allowing solar wind and magnetosheath particles to directly enter the magnetosphere. At Saturn, the nature of MP reconnection remains unclear. Masters et al. (2012) hypothesised that viable reconnection under a large difference in plasma β across the MP also requires a high magnetic shear (i.e. magnetic fields either side of the boundary close to anti-parallel).

We used electron bulk heating (i.e. the scalar temperature change) at magnetopause crossings to test hypotheses about reconnection at open magnetopause locations, and the influence of magnetic shear and plasma β. The bulk temperature was determined using three different methods, related to properties of the observed energy distribution (including methods from Lewis et al. 2008). We compared the observed heating of magnetosheath electrons with the prediction based on reconnection, using the semi-empirical relationship proposed by Phan et al. (2013) which relates the degree of bulk electron heating to the inflow Alfven speed. Figure 1 shows that Δβ-magnetic shear parameter space discriminates well between events with evidence of energisation (right) and those without (left). Based on the magnetic shear measured locally by the spacecraft either side of the MP, we find 81% of events with no energisation were situated in the ‘reconnection suppressed’ regime, and up to 68% of events with energization lay in the ‘reconnection possible’ regime. These findings support the hypotheses that magnetic shear and plasma β play a role in the viability of magnetic reconnection.

Figure 1. Assessment of diamagnetic suppression of reconnection, overlaid with electron heating ΔTe. The left and right panels show events without and with evidence of energization respectively.

Please see the paper for full details:

, , , , , & (2021). Electron Bulk Heating at Saturn’s Magnetopause. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 126, e2020JA028800. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA028800