MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Polytropic Behavior of Solar Wind Protons Observed by Parker Solar Probe

by Georgios Nicolaou (MSSL, UCL)

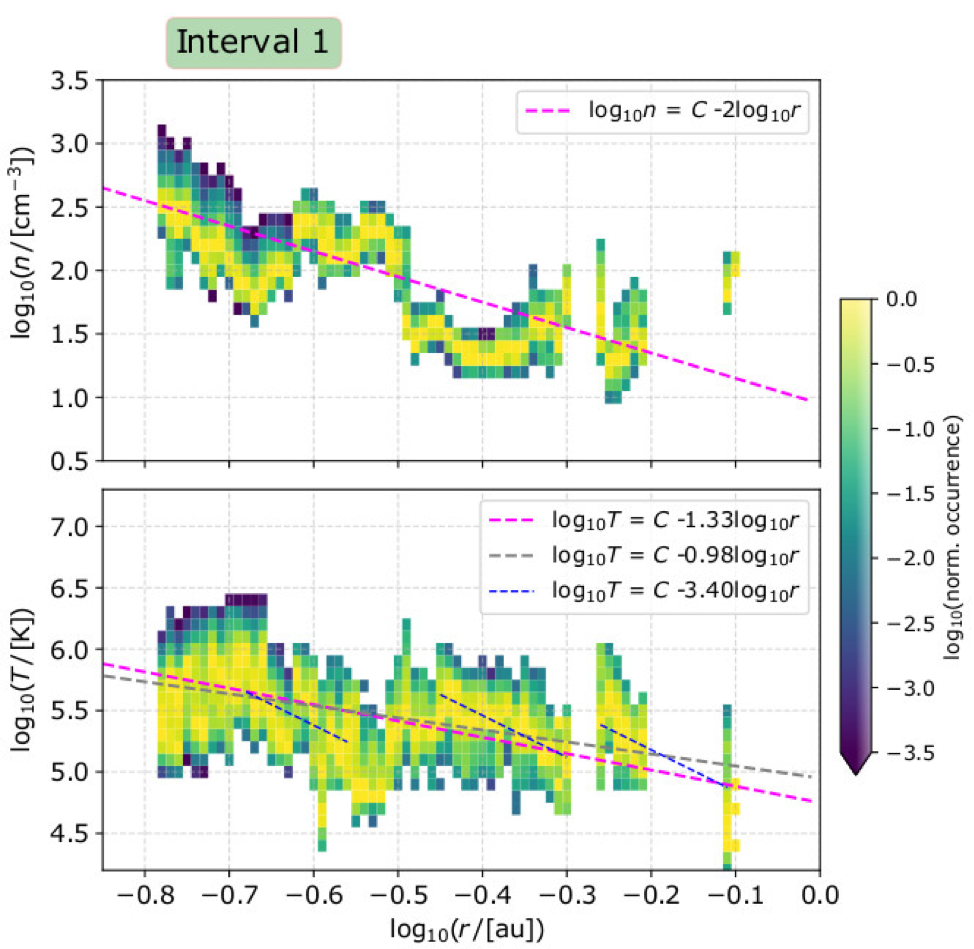

The polytropic equation relates the density and temperature of a fluid through the polytropic index. The polytropic index is a crucial parameter in understanding the physical mechanisms acting on the fluid. In this study, we investigate the large time-scale and the short time-scale fluctuations of the plasma proton density and temperature in order to determine their polytropic index. The large time-scale fluctuations which are associated with the plasma expansion within the heliosphere, follow a polytropic model with a polytropic index ~5/3. The specific behavior is consistent with an adiabatic expanding plasma protons with three degrees of freedom. The radial profile of the density follows in general, the model for a spherical expansion with a constant radial speed (see Figure 1). However, the short time-scale fluctuations, which are associated with plasma turbulence, follow a polytropic model with a polytropic index ~2.7. Interestingly, the short time-scale polytropic index is found to be correlated with the interplanetary magnetic field. We discuss the possibly of a mechanism that supplies/retains energy from the plasma protons in these short time-scales, or a mechanism that restricts the effective degrees of freedom of the protons. We finally highlight the importance of future studies that examine the polytropic index along with the characteristics of the full 3D distributions of the plasma ions and electrons.

Figure 1. Two-dimensional histograms of (top) the proton density and (bottom) the proton temperature as functions of the radial distance for time interval 1. The magenta line in the top panel shows the expected density for an expansion model with constant speed, n ∝ r-2. In the lower panel, the magenta line shows the expected temperature of a polytropic radial expansion model with γ = 5/3 while the blue lines represent expansion models with γ = 2.7. The grey line illustrates the slope determined by Huang et al. 2020 for the parallel proton temperature of fast solar wind observed by SPC.

Please see the paper for full details:

Nicolaou, G., Livadiotis, G., Wicks, R. T., Verscharen, D., Maruca, B. A., (2020). Polytropic Behavior of Solar Wind Protons Observed by Parker Solar Probe. The Astrophysical Journal, 901, 1, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/abaaae.

Evaluating the ionospheric mass source for the magnetospheres of Jupiter and Saturn

By Carley J. Martin (Lancaster University)

Ionospheric outflow is a flow of plasma initiated by a loss of equilibrium along a magnetic field line. This induces an electric field due to the separation of electrons and ions in a gravitational field. At Earth, this process is initiated by dayside reconnection in the Dungey cycle. But, is this the case at the gas giants?

Valek+ (2019) show that there is an increased outflow on field lines which map between the moon Io and the auroral oval at Jupiter, and very little in the actual polar cap. Hence, in our analysis, we evaluate over these latitudes at Jupiter and Saturn. This also means we must consider a different driver than the Dungey cycle!

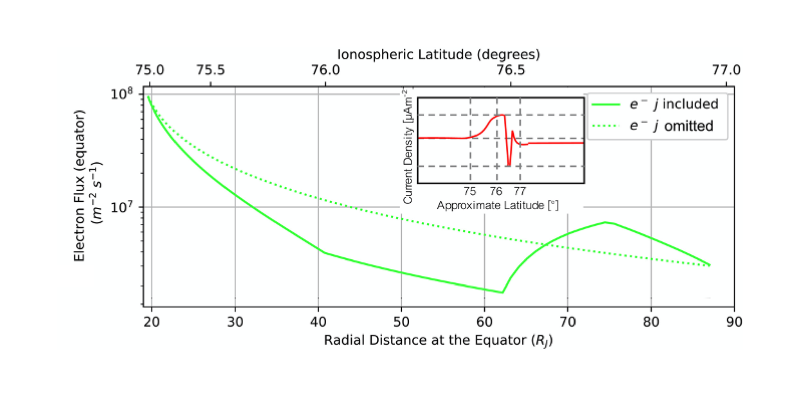

We developed a model which estimates the number of charged particles that flow from the ionospheres of Jupiter and Saturn. We also look at the effects of field aligned currents (FACs) and centrifugal forces on the total source rates of the outflow. At Saturn, the inclusion of these effects increase the total flux from the ionosphere, and it is now comparable to in situ measurements by Cassini CAPS. At Jupiter, the total particle source is found to be comparable to Io as a source of plasma in the magnetosphere. We find that the downward FACs and centrifugal force act to increase the flow of electrons from the ionosphere, and conversely upward FAC’s act to decrease outflow (see Figure below).

The additional mass flux into the inner and middle magnetospheres of Jupiter and Saturn can substantially affect the dynamics and composition and so must be included in any future assessment!

Figure shows an example of results for the electron flux mapped to the equator; solid green is with field‐aligned currents; dotted green is without field‐aligned currents. The insert shows the shape of the field‐aligned currents themselves. The electron flux is highly modified by the field‐aligned currents present, where it is enhanced by a downward current and retarded by an upward current in the auroral regions.

Please see the papers for full details:

, , , , , & , et al. (2020). The effect of field‐aligned currents and centrifugal forces on ionospheric outflow at Saturn. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2019JA027728. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027728

, , , , , & (2020). Evaluating the ionospheric mass source for Jupiter's magnetosphere: An ionospheric outflow model for the auroral regions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2019JA027727. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027727

Saturn’s Nightside Dynamics During Cassini’s F Ring and Proximal Orbits: Response to Solar Wind and Planetary Period Oscillation Modulations

By Tom J. Bradley (University of Leicester)

In this study we examined the final 44 Cassini spacecraft orbits that traversed the midnight sector of Saturn’s magnetosphere to distances of ~21 Saturn radii, in order to investigate responses to heliospheric conditions inferred from model solar wind and Cassini galactic cosmic ray (GCR) flux data.

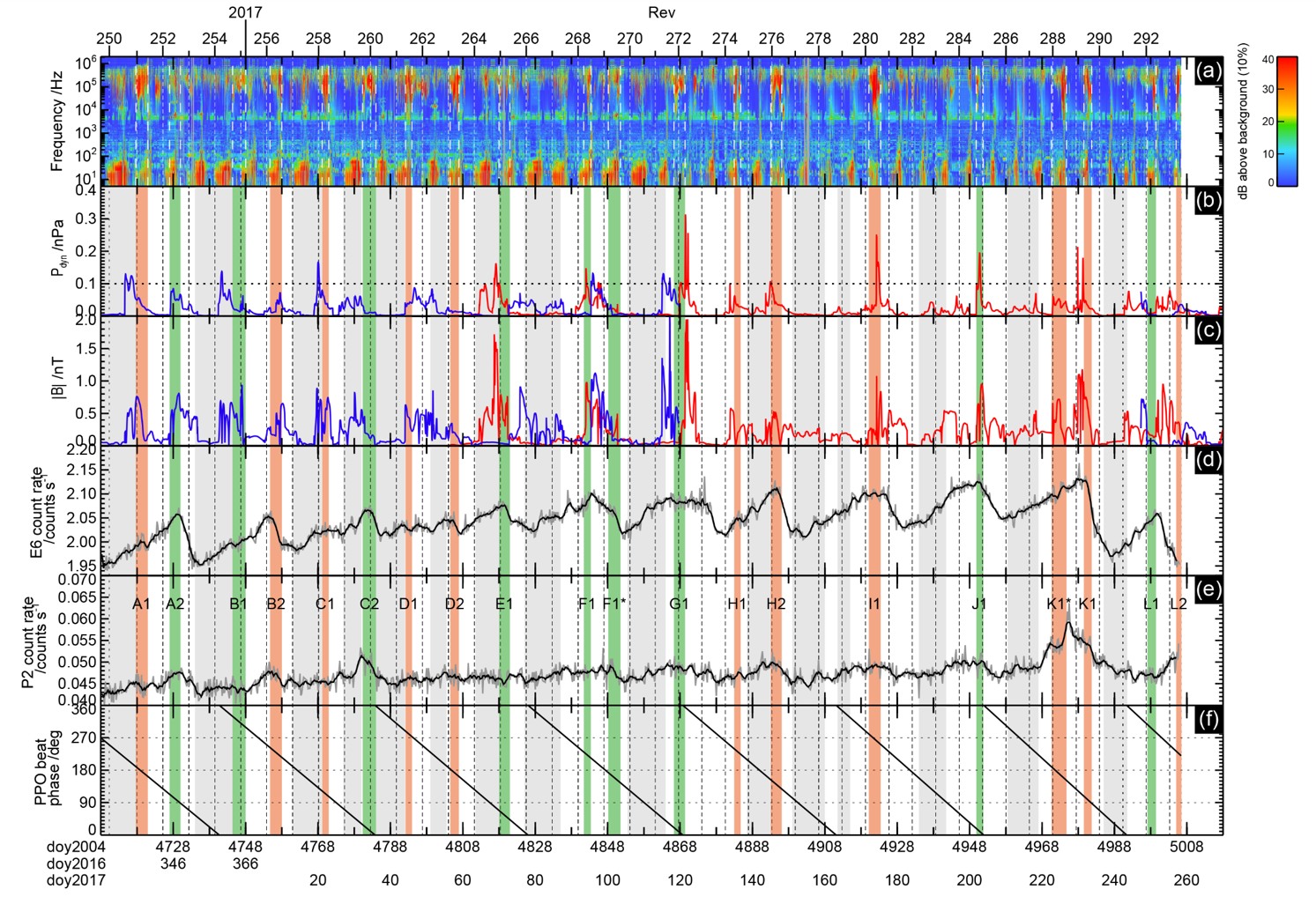

Clear responses to anticipated magnetospheric compressions were observed in magnetic field and energetic particle data, together with Saturn kilometric radiation (SKR), auroral hiss, and ultraviolet auroral emissions. Most compression events were associated with corotating interaction regions, as shown by the periodic model solar wind parameters and Forbush-like decreases in GCR fluxes in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Overview of full dataset. Figure 1a shows a RPWS spectrogram, and Figures 1b-1e show model solar wind dynamic pressure (nPa), IMF strength (nT), LEMMS channel E6 count rate (GCR flux of >120 MeV protons), and LEMMS channel P2 count rate (GCR flux as well as SEP flux of 2.3-4.5 MeV protons). Figure 1f shows the PPO beat phase (deg modulo 360°). The superposed red and green shaded vertical bands (white dashed lines in Figure 1a) show intervals of magnetospheric compression defined by criteria given above. Red corresponds to major events with an extended LFE interval (longer than one planetary rotation) and green to minor events without such an extended LFE interval. The superposed grey shaded vertical bands show intervals of relative magnetospheric quiet when energetic particle fluxes were at near-minimum values.

Each compression tended to produce ~2-3.5 day intervals of magnetospheric activity that were typically recurrent with the ~26 day solar rotation period (one or two such events per rotation). However, the responses were somewhat variable (as is shown in greater detail in the article), and were thus divided into “major” and “minor” events. Major events (red shaded bands) are those with SKR low frequency extension (LFE) intervals with durations greater than ~one planetary rotation (11 out of 20 events, or 55%), while minor events (green shaded bands) either have no noticeable LFE interval (7 out of 20 events, or 35%), or one whose duration is one planetary rotation period or less (2 out of 20 events, or 10%)

These two types of responses were found to be modulated by Saturn’s planetary period oscillations (PPOs), as follows.

- Major events are favoured when the two PPO systems are roughly in anti-phase, where they act together to thin and thicken the tail plasma sheet during each PPO cycle. The anti-phase conditions during major events result in thin plasma sheet conditions (once per rotation), that are most unstable to tail reconnection, producing energetic nightside particle injections and poleward contractions of dawn-brightened auroras.

- Minor events are favoured when the PPOs are in phase, where they act together to stabilise the plasma sheet and inhibit tail collapse, resulting in less obvious magnetospheric responses.

Overall, the results emphasize how strongly activity in Saturn’s magnetosphere is modulated by both the concurrent heliospheric conditions and the PPO modulations.

Please see the paper for full details:

Bradley, T. J., Cowley, S. W. H., Bunce, E. J., Melin, H., Provan, G., & Nichols, J. D., et al. (2020). Saturn's nightside dynamics during Cassini's F ring and proximal orbits: Response to solar wind and planetary period oscillation modulations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2020JA027907. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA027907

The visual complexity of coronal mass ejections follows the solar cycle

By Shannon Jones (University of Reading)

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), or solar storms, are huge eruptions of particles and magnetic field from the Sun. With the help of 4,028 citizen scientists, we found that the appearance of CMEs changes over the solar cycle, with CMEs appearing more visually complex towards solar maximum.

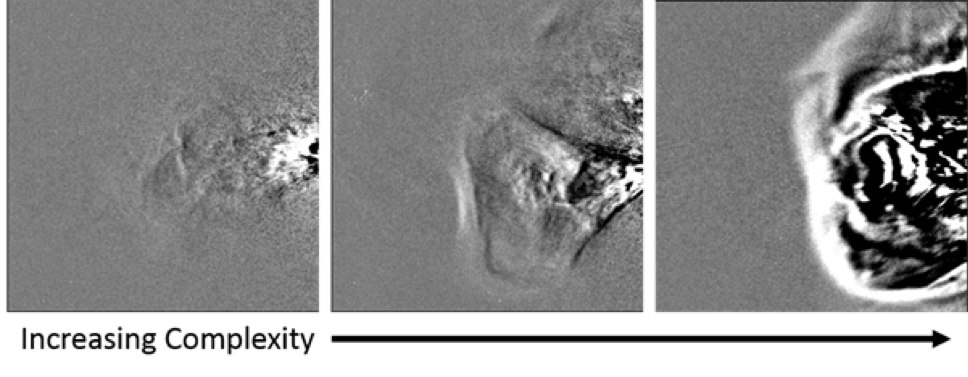

We created a Zooniverse citizen science project in collaboration with the UK Science Museum, where we showed pairs of images of CMEs from the Heliospheric (wide-angle white-light) Imagers on board the twin STEREO spacecraft, and asked participants to decide whether the left or right CME looked most complicated, or complex. We used these data to rank 1,110 CMEs in order of their relative visual complexity. Figure 1 shows three example storms from across the ranking (see figshare for an animation with all CMEs).

Figure 1. Example images showing three example CMEs in ranked order of subjective complexity increasing from low (left-hand image) through to high (right-hand image).

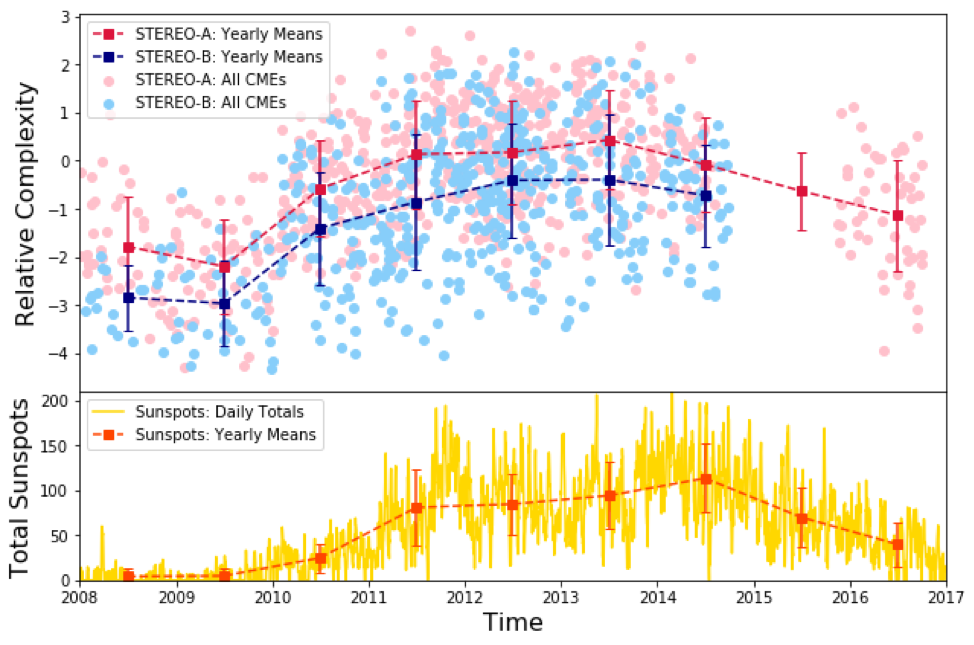

Figure 2 shows the relative complexity of all 1,110 CMEs, with CMEs observed by STEREO-A shown by pink dots, and CMEs observed by STEREO-B shown by blue dots. This shows that the annual average complexity values follow the solar cycle, and that the average complexity of CMEs observed by STEREO-B is consistently lower that the complexity of CMEs observed by STEREO-A.

These results suggest that there is some predictability in the structure of CMEs, which may help to improve future space weather forecasts.

Figure 2. Top panel: relative complexity of every CME in the ranking plotted against time. Pink points represent STEREO-A images, while blue points represent STEREO-B images. Annual means and standard deviations are over plotted for STEREO-A (red dashed line) and STEREO-B (blue dashed line) CMEs. Bottom panel: Daily total sunspot number from SILSO shown in yellow, with annual means over plotted (orange dashed line).

See the paper for more details:

Jones, S. R., C. J. Scott, L. A. Barnard, R. Highfield, C. J. Lintott and E. Baeten (2020): The visual complexity of coronal mass ejections follows the solar cycle. Space Weather, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020SW002556.

Determining the Nominal Thickness and Variability of the Magnetodisc Current Sheet at Saturn

By Ned Staniland (Imperial College London)

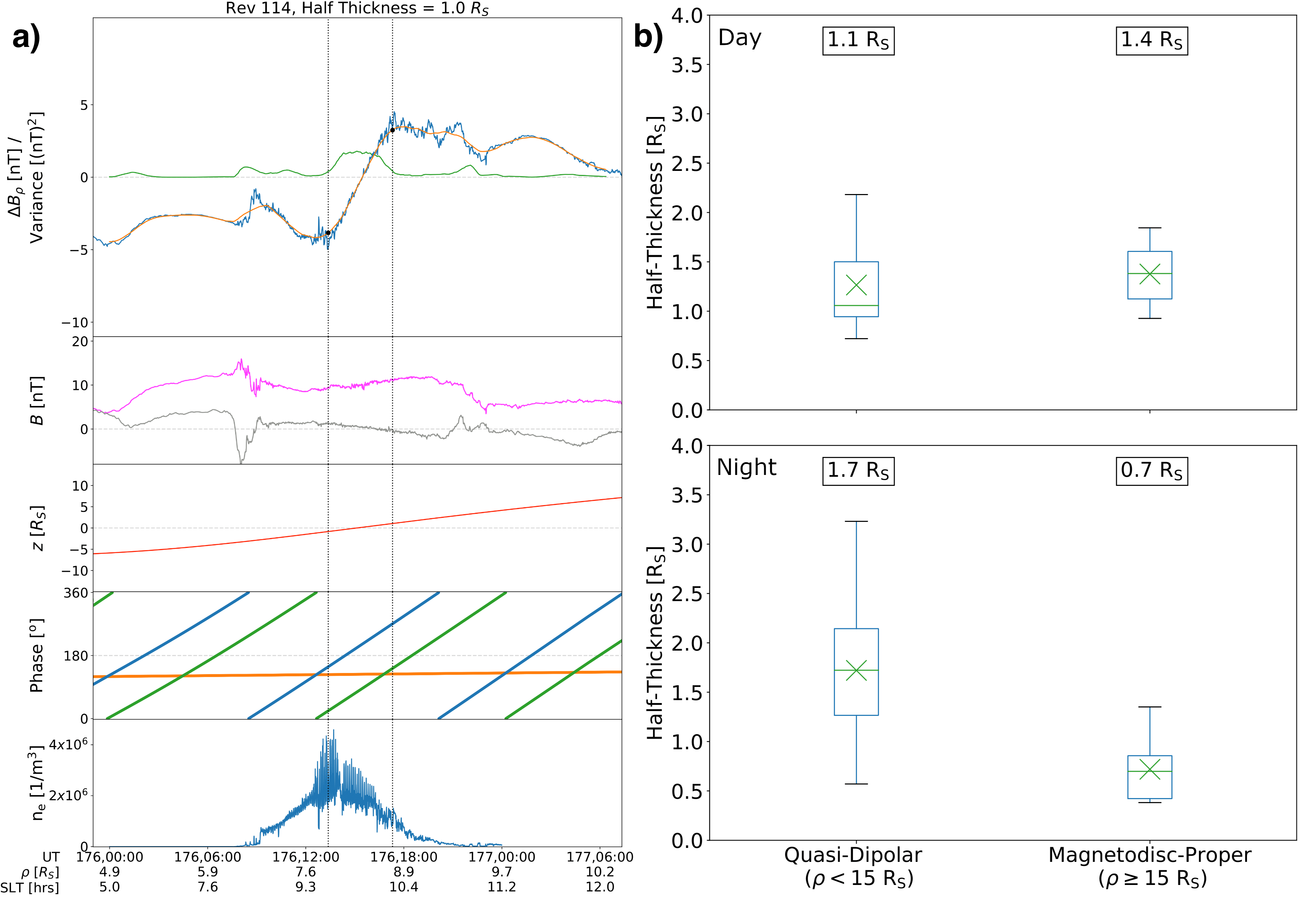

The presence of an internal plasma source (the moon Enceladus) coupled with the rapid rotation rate of Saturn (~10 hrs) results in an equatorially confined layer of plasma that stretches the dipolar planetary magnetic field into what is known as a magnetodisc. This structure is found at both gas giants and so understanding its formation and how it responds to different drivers reveals the dynamics of these magnetospheres and how the geologically active moons affect them. We explore the thickness of the equatorial current sheet that is associated with the stretched field geometry. We use 66 fast, high inclination crossings of the current sheet made by Cassini, where a clear signature in the magnetic field data (Figure 1a shows a sharp reversal in the radial field during the crossing) allows for a direct determination of its thickness and offset.

We find that the current sheet is thinner than previously calculated but identify several sources of spatial and temporal variability. For instance, the current sheet is 50% thicker in the nightside inner magnetosphere compared to the dayside (Figure 1b). This is consistent with the presence of a noon‐midnight convection electric field at Saturn that produces a hotter plasma population on the nightside, resulting in a thicker current sheet. However, the current sheet becomes thinner with radial distance on the nightside, while staying approximately constant on the dayside (Figure 1b), reflecting the solar wind compression of the magnetosphere and the stretching of the field in the tail. Some of the variability is well characterized by the planetary period oscillations (PPOs). But we also find evidence for non‐PPO drivers of variability, highlighting the interplay between different drivers that shape the Saturnian system.

This work shows the necessity for considering the variable structure of the largest current system in the Saturnian magnetosphere, which is essential particularly for future modelling efforts.

Figure 1a) shows Cassini magnetic field data during a current sheet crossing. We determine the current sheet boundaries by identifying spikes in the variance of the cylindrical radial field component (green line, top panel). Figure 1b) shows box plots calculated from the 66 crossings that highlight the radial profile and day-night asymmetry of the current sheet thickness.

For more information, please see:

Staniland, N. R., Dougherty, M. K., Masters, A., & Bunce, E. J. (2020). Determining the nominal thickness and variability of the magnetodisc current sheet at Saturn. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2020JA027794. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JA027794