MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Bifurcated Region 2 Field-Aligned Currents Associated With Substorms

By Harneet Sangha (University of Leicester)

The Earth’s field-aligned currents (FACs) are a key component of the solar wind-magnetosphere-ionosphere-atmosphere coupled system. They connect the magnetosphere to the ionosphere, forming two concentric rings of opposite polarity currents at dawn and dusk. The inner ring (Region 1, R1), at higher latitudes, connects to the magnetopause, whereas the lower latitude ring (Region 2, R2) connects to the inner magnetosphere. By studying them, we are able to observe the energy transfer throughout the system. They are highly variable, and the small scale changes can be difficult to detect. With the use of the Active Magnetosphere and Planetary Electrodynamics Response Experiment (AMPERE) (comprising 66-satellites that gather the data), we can observe these small scale, structures and variations in the FACs on short time scales.

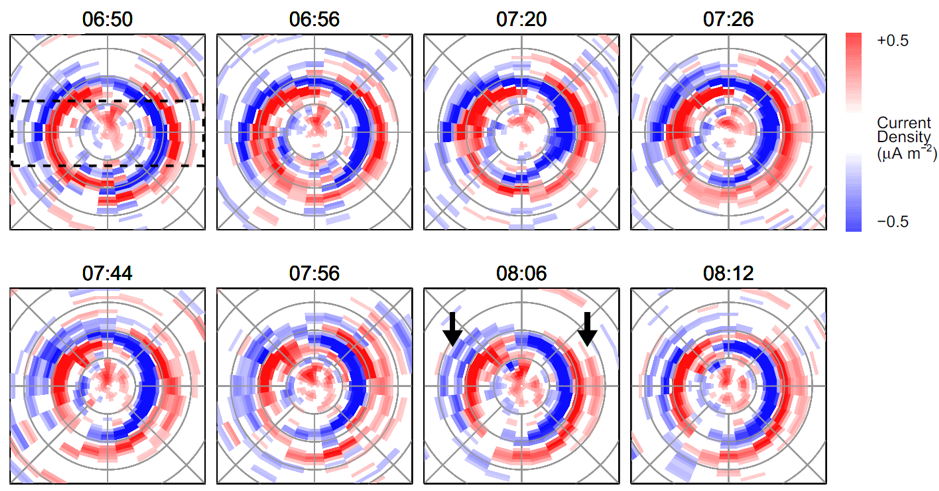

In our work, we have observed a new phenomenon which we describe as the bifurcation of the R2 currents, and the formation of a new R2 current ring (seen in Figure 1). These current signatures appear to be associated with the substorm expansion phase, and during ongoing geomagnetic activity they appear to have a 1 hour quasi-periodicity. We suggest that these bifurcations are related fast, westward flows in the midlatitude ionosphere, known as subauroral polarization streams (SAPS).

We have proposed a new mechanism that describes the formation of these current bifurcations - consecutive particle injections into the inner magnetosphere during disturbed conditions cause separate partial ring currents to form, leading to the presence of distinct R2 current systems.

Figure 1: A series of polar projections of the AMPERE current density data for the Northern Hemisphere on 2 June 2011, from 06:50 to 08:12 UT. The colour scale for downward (blue) and upward (red) FACs saturate at ± 0.5 µA/m2. Concentric circles show colatitudes in steps of 10°, and 12 MLT (local noon) is presented at the top of the plots, with 06 MLT (dawn) on the right. The dashed box shows the dawn-dusk axis. At 06:50 UT a standard R1/R2 FAC distribution is evident. The locations of interest are highlighted in the first panel with arrows, where by 07:44 UT the R2 FACs bifurcate to form two concentric rings and can be seen between 20° and 30° colatitude.

For more information, please see the paper:

Sangha, H., Milan, S. E., Carter, J. A., Fogg, A. R., Anderson, B. J., Korth, H., & Paxton, L. J. (2020). Bifurcated Region 2 field‐aligned currents associated with substorms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 125, e2019JA027041. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027041

Evaluating the Accuracy of Solar Orbiter Plasma Measurements

By Georgios Nicolaou (MSSL, UCL)

The plasma instruments on board Solar Orbiter will determine the three-dimensional velocity distribution functions of the plasma ions and electrons with high time resolution, within heliocentric distances from ~0.3 to 1 au. The analysis of these distributions will determine the plasma bulk parameters (e.g., density, velocity, and temperature). New work by Nicolaou et al. (2019, 2020) assesses the accuracy of these measurements, considering the proton and electron instruments separately.

1. The Impact of Turbulent Solar Wind Fluctuations on Proton Measurements

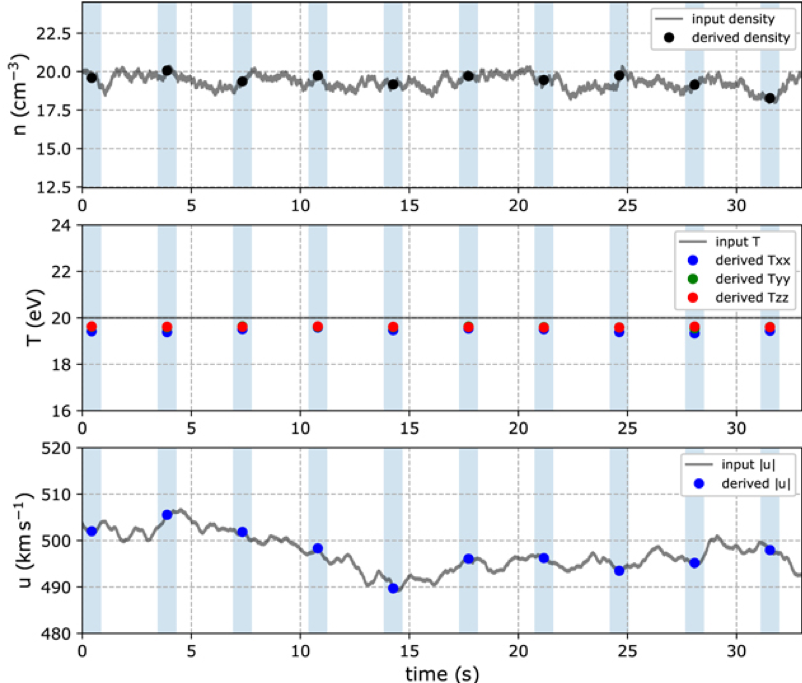

The Solar Wind Analyser’s Proton Alpha Sensor (SWA-PAS) on board Solar Orbiter will measure solar wind plasma protons. However, due to the dynamic and turbulent nature of solar wind plasma, the accurate determination of the plasma parameters from the observations is significantly challenging. Nicolaou et al. 2019, simulated turbulent solar wind proton plasma that exhibits the typical features of turbulence spectrum. They modelled the expected observations by SWA-PAS (see Figure 1) and analyzed them using standard analysis methods in order to quantify the accuracy of the derived plasma bulk parameters. The results show that the typical turbulence will not significantly affect the accuracy of the high-time resolution measurements by SWA-PAS. In addition, the authors compare the accuracy of the instrument as a function of the acquisition time and discuss the sources of errors in the derived parameters.

Figure 1. Time series of modeled solar wind with a turbulent spectrum consisting of Alfvén waves and slow modes and a comparison to derived moment parameters from the expected SWA-PAS observations at lower resolution. Each panel shows the input data (gray line) and the moments derived from the modeled observations (bullets). The shadowed areas represent the time intervals in which the instrument collects counts to construct an entire 3D VDF. The top panel shows the plasma density the middle panel shows the diagonal elements of the plasma temperature tensor, and the bottom panel shows the plasma bulk speed. Besides the small systematic underestimation of the plasma density and plasma temperature, the derived moments suggest that the accuracy of SWA-PAS measurements, under typical turbulent solar wind conditions, is remarkably high.

2. Determining the Bulk Parameters of Plasma Electrons from Pitch-Angle Distribution Measurements

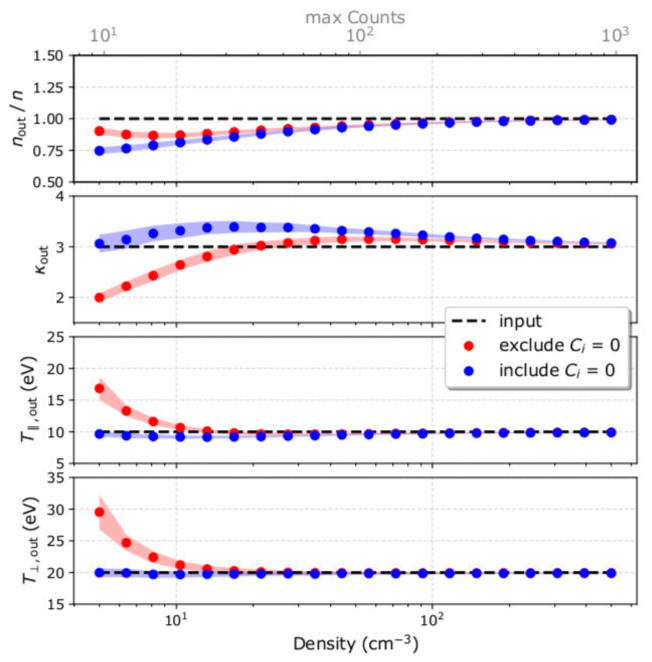

The Solar Wind Analyser’s Electron Analyser System (SWA-EAS) is designed to observe the solar wind electrons. In burst-mode operations, the instrument will obtain measurements in the 2D velocity space (as opposed to full 3D velocity distributions) in order to construct the pitch angle distributions of plasma electrons. The reduction of one dimension reduces the statistical significance of the observations and makes the analysis more challenging. Nicolaou et al. 2020, investigate the expected accuracy of the derived bulk parameters of supra-thermal electrons, which are often described by kappa distribution functions. They simulate the expected observations within the heliocentric distance range from 0.3 to 1 au and derive the plasma bulk parameters by fitting the synthetic observations (see Figure 2). The study shows that the proper fitting analysis of the measurements can derive the plasma parameters with significant accuracy, even at 1 au, where the expected particle flux is very low.

Figure 2. (From top to bottom) The derived electron density over input density, kappa index, parallel and perpendicular temperature as functions of the input plasma density. The red points represent the mean values (over 200 samples) of the parameters derived by fitting only the measurements with Ci ≥ 1. The blue points represent the mean values of the parameters derived by fitting to all measurements including those with Ci = 0. The shadowed regions represent the standard deviations of the derived parameters. The dashed lines represent the input parameters.

For more information, please see the papers:

Nicolaou, G., Verscharen, D., Wicks, R. T., & Owen, C. J. (2019). The Impact of Turbulent Solar Wind Fluctuations on Solar Orbiter Plasma Proton Measurements. The Astrophysical Journal, 886:101. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab48e3

Nicolaou, G., Wicks, R., Livadiotis, G., Verscharen, D., Owen, C., & Kataria, D. (2020). Determining the Bulk Parameters of Plasma Electrons from Pitch-Angle Distribution Measurements. Entropy, 22, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/e22010103

Modelling the temporal variability in Saturn's magnetotail current sheet from the Cassini F‐ring orbits

By Omakshi Agiwal (Imperial College London)

The Cassini spacecraft completed 20 high latitude orbits known as the ‘F-ring orbits’ during the end of mission (corresponding to northern Saturnian summer). Each orbit provided a ~2 day sample of the magnetotail region, where the measured radial magnetic field Br and the position of the magnetic equator/magnetotail current sheet centre (indicated by Br=0) showed significant orbit-to-orbit variability, despite a highly repeatable spacecraft trajectory.

Our work considers two well-known sources of temporal variability in the Saturnian magnetosphere:

- Solar wind forcing, which acts to displace the magnetic equator from the rotational equator. The forcing increases with radial distance from the planet and is variable with solar wind conditions on ~ week-long timescales.

- Planetary period oscillations (PPO), which refer to two magnetic perturbation systems (one in each hemisphere) that rotate independently around Saturn’s spin/dipole axis with periods of ~10.7 hours. They modulate the vertical position and thickness of the magnetotail current sheet depending on their relative strength and phase.

Figure 1: (a) Illustrates the spacecraft (blue dot) traversing our temporally variable modelled current sheet, shown by the shaded grey region. The position of the magnetic equator is shown by the dashed black line. The two arrows on the polar-plot show an equatorial projection of the northern (blue) and southern (red) PPO fields rotating with a ~ fixed relative phase (ΔΦ), with the spacecraft on the nightside. (b) Shows the time-series of Br measured by the magnetometer (solid grey line) and the modelled (dashed orange line) from our work. (c) Illustrates the temporal evolution of the z-position of the magnetic equator and the thickness of the current sheet from the model.

Figure 1: (a) Illustrates the spacecraft (blue dot) traversing our temporally variable modelled current sheet, shown by the shaded grey region. The position of the magnetic equator is shown by the dashed black line. The two arrows on the polar-plot show an equatorial projection of the northern (blue) and southern (red) PPO fields rotating with a ~ fixed relative phase (ΔΦ), with the spacecraft on the nightside. (b) Shows the time-series of Br measured by the magnetometer (solid grey line) and the modelled (dashed orange line) from our work. (c) Illustrates the temporal evolution of the z-position of the magnetic equator and the thickness of the current sheet from the model.

We combine models that consider the effects of each perturbation source on Br, and the model output for the magnetotail pass of an example orbit is shown in Figure 1. Overall, we show that the temporal variability in 90% of the F-ring orbits is consistent with the expected variability due to solar wind forcing and dual-PPO modulation. This demonstrates an understanding of the key sources of large scale variability in Saturn’s magnetotail, and shows that magnetotail dynamics can reliably be studied using high latitude orbits (which is novel in our method).

For more information, please see the paper:

Agiwal, O., Hunt, G. J., Dougherty, M. K., Cowley, S. W. H., & Provan, G. ( 2019). Modelling the temporal variability in Saturn's magnetotail current sheet from the Cassini F‐ring orbits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027371

Active Region Modulation of Coronal Hole Solar Wind

By Allan Macneil (University of Reading)

The solar wind is the continuous outflow of plasma from the Sun’s atmosphere (the corona) into interplanetary space along ‘open’ magnetic field. The mechanisms which produce the solar wind; opening the coronal magnetic field, accelerating the plasma, and imbuing it with a range of compositional and dynamical properties, are not fully understood. 'Coronal holes’, which are regions of open magnetic field, are known to be the source of the ‘fast’ (v > 500 km/s) solar wind. However, the origins of ‘slow’ (v < 400 km/s) solar wind are unclear, particularly as slow wind properties imply origins in closed magnetic field regions. We present a case study into one candidate slow wind source: active regions.

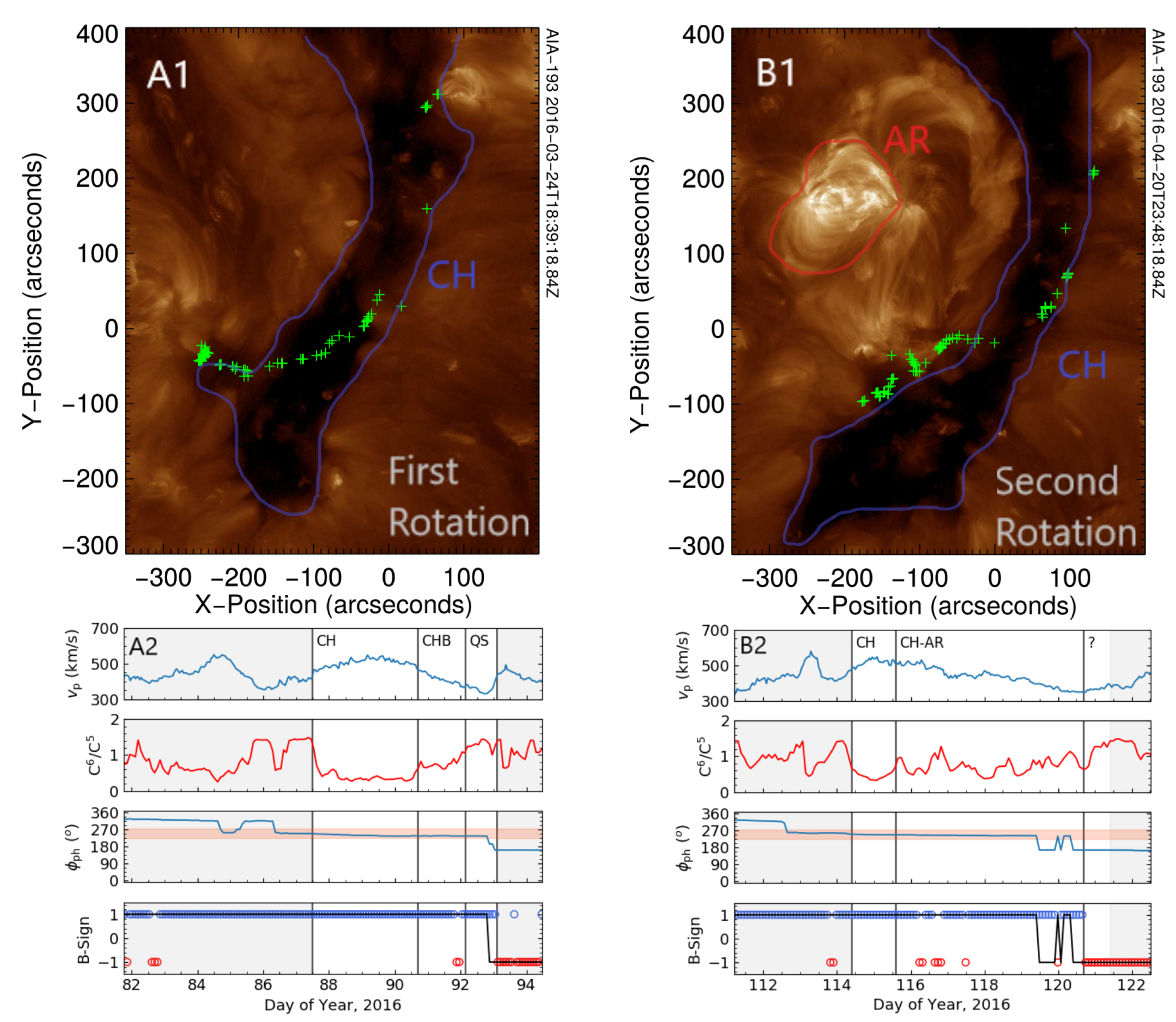

Figure 1: Top row shows EUV solar images of the source coronal hole (CH), and the CH plus active region (AR) during the first and second rotations. The CH and AR are outlined in blue and red, and green crosses show the location of mapped solar wind source locations. The lower panels show in situ and mapping time series are shown for each associated solar wind period.

Active regions are locations of concentrated magnetic flux. They are associated with bright loops in the corona, and are a possible slow solar wind source. In April 2016, an active region emerged at the eastern boundary of a coronal hole which had produced Earth-directed solar wind one solar rotation prior (see Figure 1). This unique observational configuration is shown in Figure 1. We study what changes the newly-emerged active region causes in the solar wind, by contrasting linked in situ solar wind and remote sensing coronal observations between the two periods. Primarily, we find that the active region causes increased variability in composition and structuring of the solar wind located at the edge of the coronal hole stream. We conclude that this new variability is most likely due to interaction between the active region and the coronal hole in the form of loop-opening interchange reconnection. This process changes the open field topology around the coronal hole boundary, and may sporadically release plasma of a range of properties from previously closed magnetic fields into the solar wind.

For more information, please see the paper:

Macneil, A. R., Owen, C. J., Baker, D., et al. (2019). Active Region Modulation of Coronal Hole Solar Wind. The Astrophysical Journal, 887(2), 146, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab5586

Electron Diffusion by Wave-Particle Interactions in the Radiation Belt

By Oliver Allanson (University of Reading)

The Earth's outer radiation belt is a dynamic and extended radiation environment within the inner magnetosphere, composed of energetic plasma that is trapped by the geomagnetic field. The size and location of the outer radiation belt varies dramatically in response to solar wind variability - orders of magnitude changes in the electron flux can occur on short timescales (~hours). However, it is very challenging to accurately predict, or model, fluxes within the radiation belt. This is a pressing concern given the hundreds of satellites that orbit within this hazardous environment, and so the prediction of its variability is a key goal of the magnetospheric space weather community (e.g. see Horne et al., 2013).

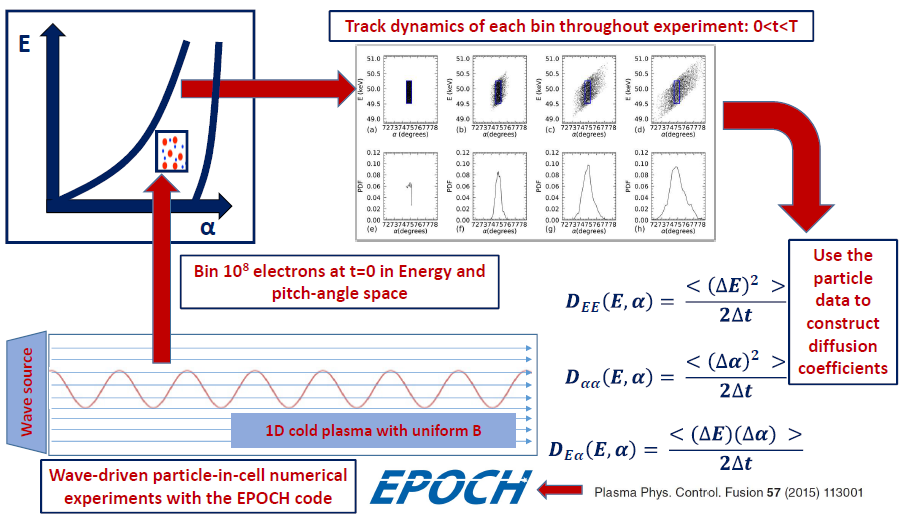

Most physics-based computer models of particle dynamics in the radiation belts rely upon the assumption of slow perturbations to electron distributions due to interactions with low amplitude electromagnetic waves. However, satellite observations have shown that high amplitude waves and correspondingly large changes in electron distributions are not rare (e.g. see a recent example with observations from the ARASE satellite in Kurita et al., 2018). In our novel electromagnetic particle-in-cell numerical experiments, we analyse the diffusion in energy and pitch angle space of 100 million individual high-energy electrons in conditions typical of the radiation belt environment - due to interactions with externally driven electromagnetic waves. The method is illustrated in Figure 1. We present two main conclusions:

(i) On very short timescales (~0.1 second) we observe an initial ‘anomalous’ electron response, for which the rate of diffusion is nonlinear in time.

(ii) After the initial transient phase we observe a normal diffusive response that is consistent with quasilinear theory.

Figure 1: A schematic illustrating the particle-in-cell numerical experiment.

The results demonstrate the exciting capabilities of our new experimental technique. Here we prove the concept for conditions that are unlikely to deviate from standard theory, and in future experiments this framework will allow us to investigate the changing nature of the electron response with increased electromagnetic wave amplitude.

For more information, please see the paper:

Allanson, O., Watt, C. E. J., Ratcliffe, H., Meredith, N. P., Allison, H. J., Bentley, S. N., et al. ( 2019). Particle‐in‐cell experiments examine electron diffusion by whistler‐mode waves: 1. Benchmarking with a cold plasma. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA027088