MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Long-term variations in solar wind parameters, magnetopause location, and geomagnetic activity over the last five solar cycles

by Andrey Samsonov (Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UCL)

The magnetopause is a natural boundary between the solar wind and magnetospheric plasmas. Geosynchronous orbit, where numerous communications, meteorological and GPS satellites operate, is usually located in the magnetosphere but occasionally due to variable solar wind conditions the magnetosphere may significantly compress and those satellites will cross the magnetopause and get in direct contact with the solar wind plasma. Fast streams of dense solar wind plasma as well as solar energetic particles might damage the satellites. Therefore the study of variations of the magnetopause standoff distance is an important problem of space physics. The magnetopause location can be described by empirical models (e.g. Shue et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2010).

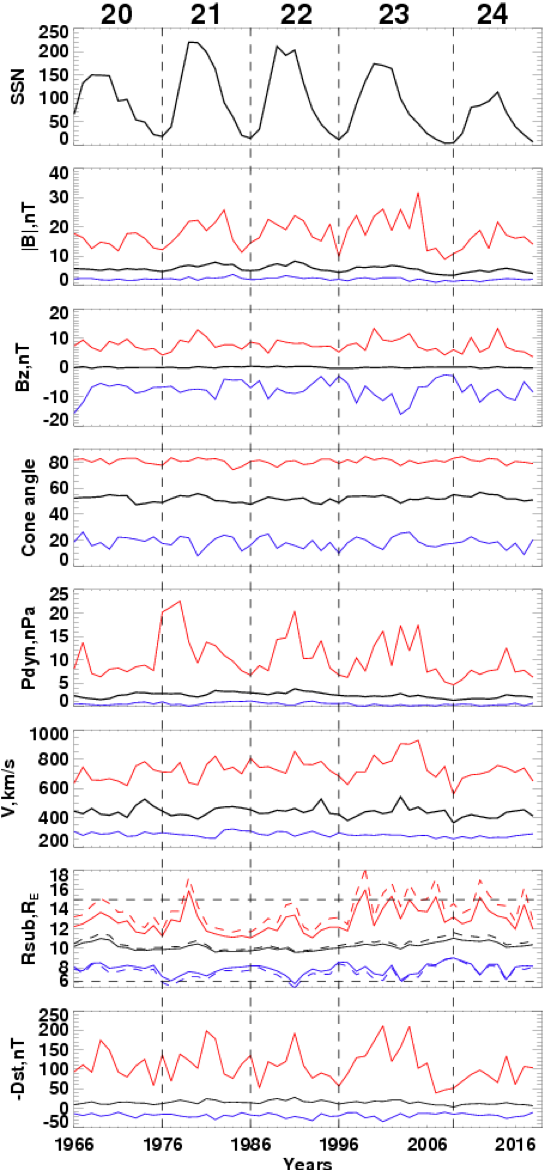

In our recent work, we studied long term changes in the magnetopause position. We use both OMNI solar wind observations and empirical magnetopause models to reconstruct time series of the magnetopause standoff distance for nearly five solar cycles (from 1966 to 2018). The magnetopause standoff distance on this time scale depends mostly on the solar wind dynamic pressure (Pdyn). The 11-year solar cycles in the Pdyn variations are superimposed by an increasing trend before 1991 and a decreasing trend between 1991 and 2009. Correspondingly, we find that the standoff distance predicted by magnetopause models increases by nearly 2 RE from 1991 to 2009. The annual sunspot number (SSN), IMF magnitude and magnetospheric geomagnetic activity indices display the same trends as the dynamic pressure. We calculate extreme solar wind parameters and magnetopause standoff distance in each year using daily values and find that both extremely small and large standoff distances during a solar cycle preferably occur at solar maximum rather than at solar minimum (see figure below).

Furthermore, we calculated correlations between annual average solar wind and magnetospheric parameters, and the SSN. The annual IMF magnitude well correlates with SSN with a zero time lag, while the annual Pdyn correlates reasonably well with the SSN but with 3-years time lag. Both the annual solar wind density and velocity well correlate with the dynamic pressure, but the correlation coefficient is higher for density than for velocity. The annual Kp index better correlates with Pdyn, while Dst index better correlates with Bs (negative IMF Bz). This correlation analysis helps to better understand relations between solar, solar wind and magnetospheric parameters on the long time scale.

The knowledge of predicted magnetopause position for the next solar cycle is important for future space missions, especially for those which are intended to observe the dayside magnetopause whether in situ or remotely. One of the forthcoming missions which will study variations of the dayside magnetopause is the Solar Wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer (SMILE).

For more information, please see the paper below:

Samsonov, A. A., Bogdanova, Y. V., Branduardi‐Raymont, G., Safrankova, J., Nemecek, Z., & Park, J.‐S. ( 2019). Long‐term variations in solar wind parameters, magnetopause location, and geomagnetic activity over the last five solar cycles. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026355

Figure: The sunspot numbers, average and extreme IMF magnitude and Bz, IMF cone angle (the angle between IMF vector and xaxis), solar wind dynamic pressure and velocity, magnetopause standoff distance (solid lines for Shue et al.'s model and dashed lines for Lin et al.'s model), and geomagnetic Dst index. Annual average values shown by black, daily maximal and minimal values for each year shown by red and blue. Vertical lines separate solar cycles as indicated by numbers at the top.

Origin of the extended Mars radar blackout of September 2017

By Beatriz Sánchez-Cano (University of Leicester)

Several instrument operations, as well as communication systems with rovers at the surface, depend on radio signals that propagate throughout the atmosphere of Mars. This is the case for two radars currently operational in Mars’ orbit, sounding the ionosphere, surface and subsurface of the planet: The Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) on board Mars Express, which operates between 0.1 and 5.5 MHz, and the Shallow Radar (SHARAD) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which operates at 20 MHz. However, both radars typically suffer from complete blackouts for several days (and even weeks) when solar storms hit Mars. It is thought that an increase in the electron density of the lower ionosphere below 100 km occurs, where even a small enhancement in ionization significantly increases the signal attenuation. In analogy with Earth, some works suggest that solar protons of tens of MeV can cause these absorption layers. However, at Mars, the current origin andlong duration is not known.

Sánchez-Cano et al. (2019) focused on both the MARSIS and SHARAD radar performances during a powerful solar storm that hit Mars in September 2017. The space weather event consisted of a X8.2-class flare emitted by the Active Region 12673 at the western limb of the solar disk on 10 September 2017 (Figure 1a). This was followed by solar energetic particles (ions and electrons) that arrived at Mars few hours later, as recorded by the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) mission (see Figure 1b,c). Based on MAVEN observations and numerical simulations of energetic electron precipitation, Sánchez-Cano et al. (2019) found that high energy electrons (and not protons) were the main ionization source, creating a dense layer of ions and electrons of magnitude ~1010 m-3 at ~90 km on the Martian nightside. For frequencies between 3 and 20 MHz, the peak absorption level is found at 70 km altitude, and the layer was composed mainly of O2+, the main Martian ionosphere component. This layer attenuated radar signals continuously for 10 days, preventing the radars from receiving any HF signals from the planetary surface across a planetary scale (Figure 1d). This contrasts with the typical few hour durations that these phenomena have at Earth.

This work highlights the need for careful assessments of radar performances for future operational systems, especially during space weather events. During these events, a good characterization of the low ionosphere is necessary for radar operations (and other instruments that use HF radio links), operational planning, as well as for communications with the Martian surface in the HF range.

For more information please see the paper below:

Sánchez‐Cano, B., Blelly, P.‐L., Lester, M., Witasse, O., Cartacci, M., Orosei, R., et al ( 2019). Origin of the extended Mars radar blackout of September 2017. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026403

Figure 1: (a) MAVEN-EUV irradiance observations of wavelength 0.1-7 nm. (b) MAVEN-SEP ion differential flux spectra. (c) MAVEN-SEP electron differential flux spectra. (d) Each symbol denotes when MARSIS and SHARAD were in operation. Empty symbols designate the cases when the surface was observed, and filled symbols when was not observed. The exception are green diamonds that indicate the times when SHARAD observed a highly blurry surface.

Equatorial magnetosonic waves observed by Cluster satellites: The Chirikov resonance overlap criterion

by Homayon Aryan (University of Sheffield)

Numerical codes modelling the evolution of the radiation belts often account for wave-particle interaction with magnetosonic waves. The diffusion coefficients incorporated in these codes are generally estimated based on the results of statistical surveys of the occurrence and amplitude of these waves. These statistical models assume that the spectrum of the magnetosonic waves can be considered as continuous in frequency space, however, this assumption can only be valid if the discrete nature of the waves satisfy the Chirikov resonance overlap criterion.

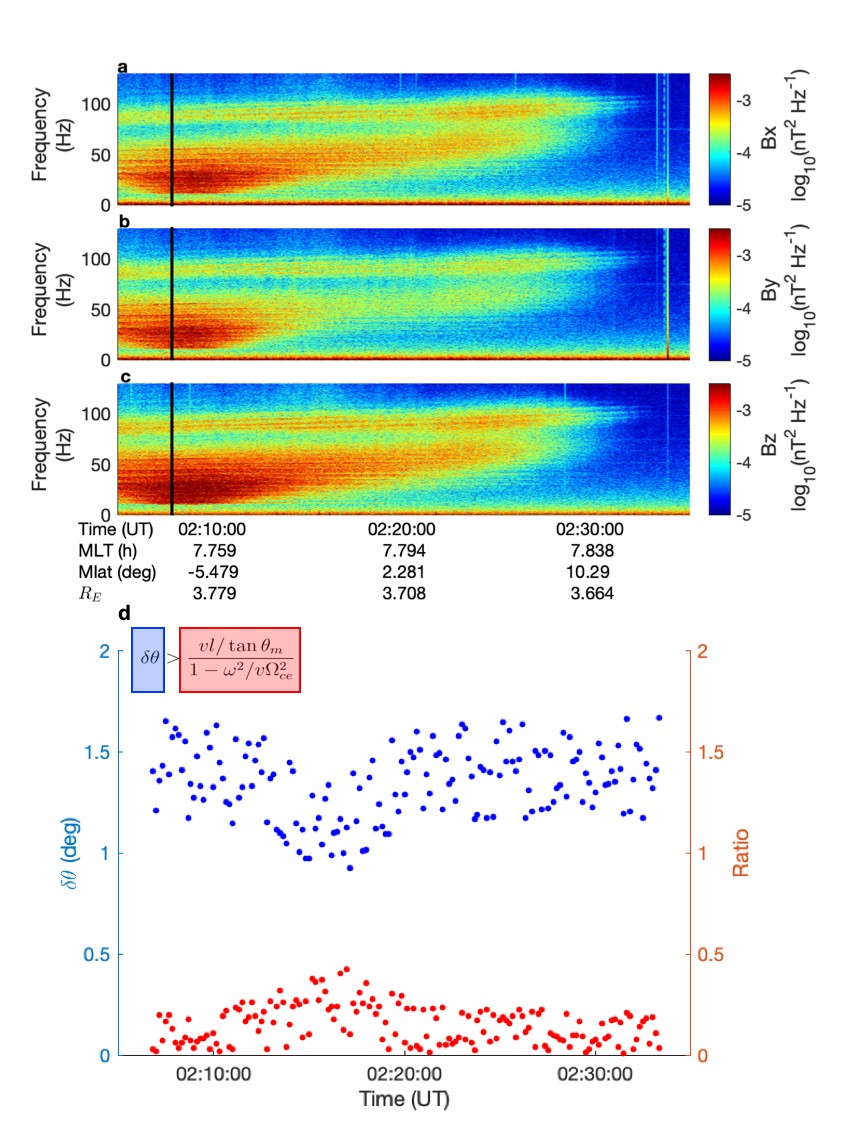

The Chirikov resonance overlap criteria describes how a particle trajectory can move between two resonances in a chaotic and unpredictable manner when the resonances overlap, such that it is not associated with one particular resonance [Chirikov, 1960]. It can be shown that the Chirikov resonance overlap criterion is fulfilled if the following equation is satisfied:

δθ = (vl / tanθm) / (1 - (ω2/vΩce2))

where θm is the mean angle between the propagation direction and the external magnetic field, δθ is the standard deviation of the wave propagation angles , l is the harmonic number, v=me/mp is the electron to proton mass ratio, and Ωce is the electron gyro-frequency [Artemyev et al., 2015].

Here we use Cluster observations of magnetosonic wave events to determine whether the discrete nature of the waves always satisfy the Chirikov resonance overlap criterion, extending a case study by Walker et al. [2015]. An example of a magnetosonic wave event is shown in panels a-c of the Figure. Panel d shows that the Chirikov overlap criterion is satisfied for this case. However, a statistical analysis shows that most, but not all, discrete magnetosonic emissions satisfy the Chirikov overlap criterion. Therefore, the use of the continuous spectrum, assumed in wave models, may not always be justified. We also find that not all magnetosonic wave events are confined very close to the magnetic equator as it is widely assumed. Approximately 75% of wave events were observed outside 3° and some at much higher latitudes ~21° away from the magnetic equator. This observation is consistent with some past studies that suggested the existence of low-amplitude magnetosonic waves at high latitudes. The results highlight that the assumption of a continuous frequency spectrum could produce erroneous results in numerical modelling of the radiation belts.

For more information please see the paper below:

, , , & ( 2019). Equatorial magnetosonic waves observed by Cluster satellites: The Chirikov resonance overlap criterion. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JA026680

Figure: Observation of a magnetosonic wave event measured by Cluster 2 on 16 November 2006 at around 02:08 to 02:33~UT. The top three panels (a, b, and c) show the dynamic wave spectrogram (Bx, By, and Bz respectively) measured by STAFF search coil magnetometer. Panel d shows the analysis of the Chirikov resonance overlap criterion outlined in equation shown on top-left of the panel. The blue and red dots represent 10~s averaged values of dqand the ratio on the right hand side of equation respectively.

How well can we estimate Pedersen conductance from the THEMIS white-light all-sky cameras?

by Mai Mai Lam (University of Southampton)

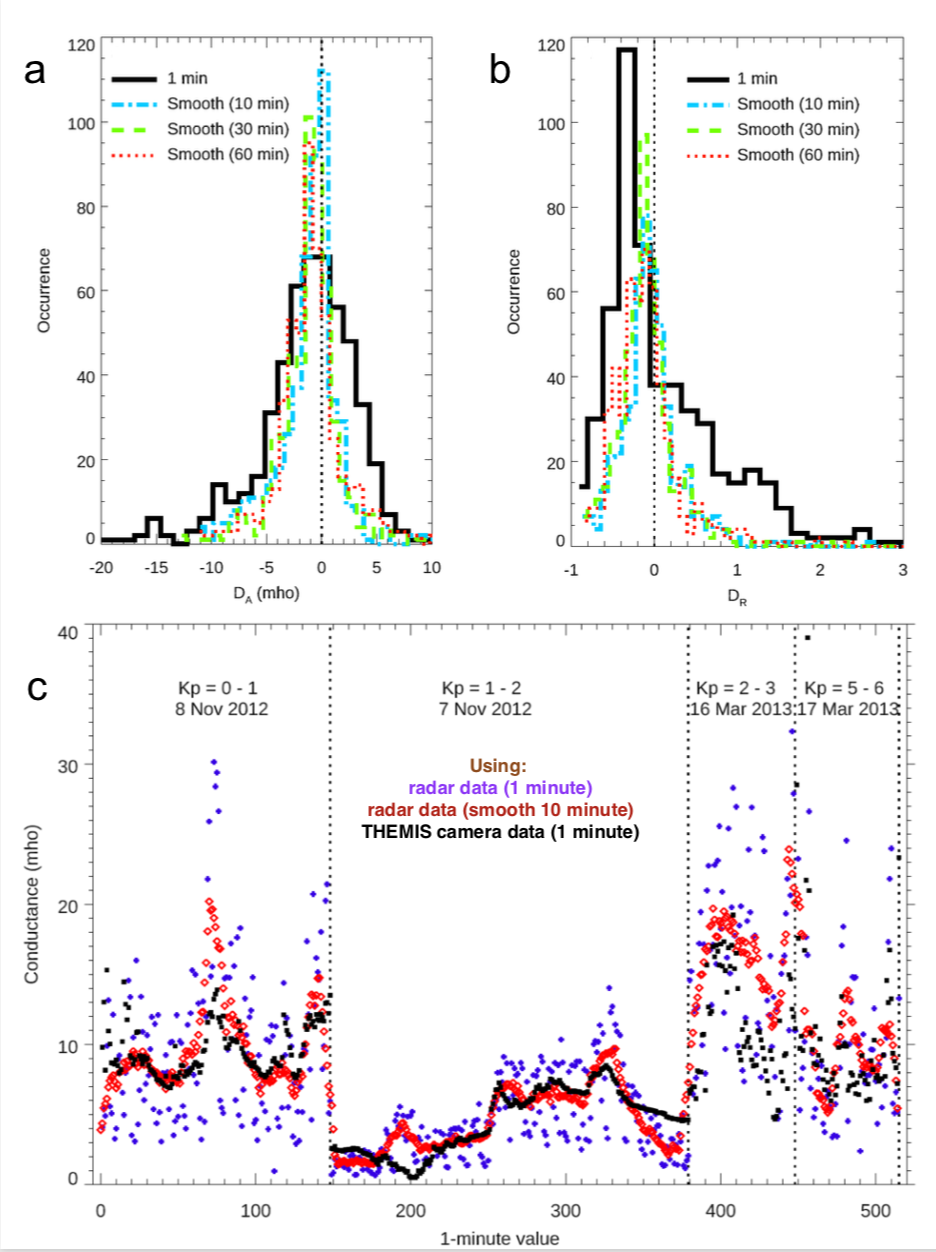

The substorm cycle comprises the loading and explosive release of magnetic energy into the Earth system, causing complex and brilliant auroral light displays as large as a continent. Within one substorm, over 50% of the total solar wind energy input to the Earth system is estimated to be converted to Joule heating of the atmosphere.Such Joule heating is highly variable, and difficult to measure for individual substorms. One quantity that we need to measure in order to calculate the Joule heating is the distribution of Pedersen conductance. Ideally this should be done across the very large range of latitudes and local times that substorms expand into. Pedersen conductance can be examined with high accuracy by exploiting ground-based incoherent scatter radar data, but only on the scale of a few kilometres.

The THEMIS all-sky imagers form a network of nonfiltered cameras that spans North America. Previous results have shown that the optical intensity of a single ground camera with a green filter can be used to find a reasonable estimate of Pedersen conductance. Therefore we asked whether THEMIS white-light cameras could measure the conductance as precisely as radars can, but at multiple locations across a continent. We found that the conductance estimated by one THEMIS camera has an uncertainty of 40% compared to the radar estimates on a spatial scale of 10 – 100 km and a timescale of 10 minutes. In addition, our results indicate that the THEMIS camera network could identify regions of high and low Pedersen conductance on even finer spatio-temporal scales. This means we can use the THEMIS network, and its data archive, to learn more about how much substorms heat up the atmosphere and how complicated and changeable this behaviour is.

For more information please see the paper below:

“How well can we estimate Pedersen conductance from the THEMIS white‐light all‐sky cameras?”, M. M. Lam , M. P. Freeman, C. M. Jackman, I. J. Rae, N. M. E. Kalmoni, J. K. Sandhu, C. Forsyth. Journal of Geophysical Research. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026067

Figure caption: (a) Absolute difference between camera- and radar-derived 1 min Pedersen conductance (black solid) and the effect of different temporal smoothing (coloured broken). (b) As for a, but for the relative difference between camera- and radar-derived Pedersen conductance (normalised to the radar conductance). (c) Comparison of camera-derived and radar-derived Pedersen conductance values for days with different geomagnetic conditions as indicated by Kp: 1 min radar values (blue crosses), 1 min radar values smoothed over 10 min (red diamonds), and 1 min values derived from camera intensity (black squares).

The magnetopause booms like a drum due to impulses

by Martin Archer (Queen Mary University of London)

The abrupt boundary between a magnetosphere and the surrounding plasma, the magnetopause, has long been known to support surface waves which travel down the flanks. However, just like a stone thrown in a pond causes ripples which spread out in all directions, impulses acting on our magnetopause should also cause waves to travel towards the magnetic poles. It had been proposed that the ionosphere might result in a trapping of surface wave energy on the dayside as a standing wave or eigenmode of the magnetopause surface. This mechanism should act as a global source of magnetopause dynamics and ultra-low frequency waves that might then drive radiation belt and auroral interactions.

While many potential impulsive drivers are known, no direct observational evidence of this process had been found to date and searches for indirect evidence had proven inconclusive, casting doubt on the theory. However, Archer et al. (2019) show using all five THEMIS spacecraft during their string-of-pearls phase that this mechanism does in fact occur.

Figure: THEMIS observations and a schematic of the magnetopause standing wave.

They present observations of a rare isolated fast plasma jet striking the magnetopause. This caused motion of the boundary and ultra-low frequency waves within the magnetosphere at well-defined frequencies. Through comparing the observations with the theoretical expectations for several possible mechanisms, they concluded that the jet excited the magnetopause surface eigenmode – like how hitting a drum once reveals the sounds of its normal modes.

Hear the signals as audible sound here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mcG03NBJf-s

For more information please see the paper below:

‘Direct Observations Of A Surface Eigenmode Of The Dayside Magnetopause’. M.O. Archer, H. Hietala, M.D. Hartinger, F. Plaschke, V. Angelopoulos. Nature Communications. | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08134-5