MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

The surprisingly variable current system inside Saturn’s D ring

by Gabby Provan & Stan Cowley (University of Leicester)

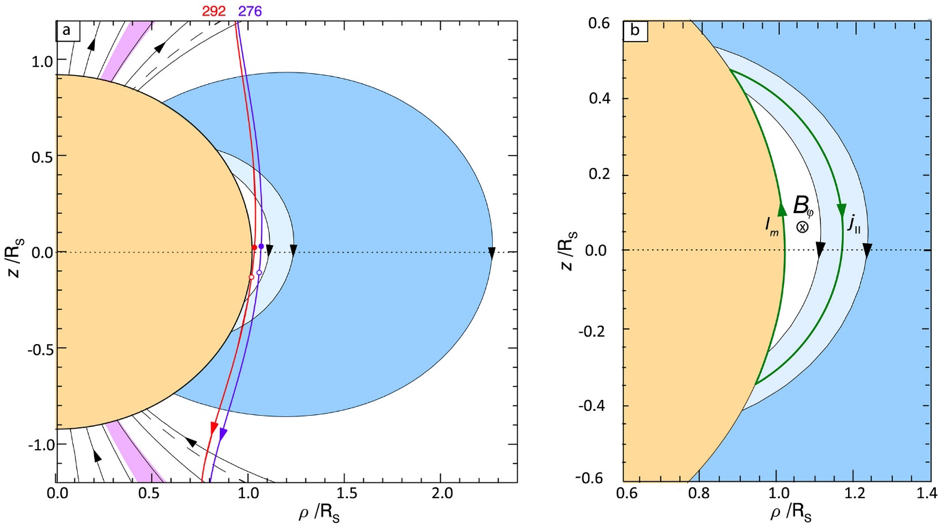

During Cassini’s Grand Finale, the spacecraft made 22 daring “proximal” periapsis passes between the denser layers of Saturn’s upper atmosphere and the inner edge of the planet’s innermost D ring (Figure 1a). This region had never previously been explored. On every pass Cassini’s magnetometer observed unanticipated perturbations in the azimuthal magnetic field component, confined to field lines that pass through and inside of the D ring in the equatorial plane, peaking typically at a few tens of nano-Tesla. Since the fields are near-symmetric about the magnetic equator, they are consistent with interhemispheric currents flowing along the near-equatorial magnetic field lines, as illustrated in Figure 1b.

Here we examine the azimuthal field perturbations on all the proximal passes, and show that they are surprisingly variable in form and magnitude. While a third of the passes indicate a unidirectional current flow, and a further third shows multiple sheets of oppositely-directed currents. The remaining passes present diverse signatures, including two passes showing reverse currents, and two with only small and fluctuating perturbations. This variability is not related to the spacecraft trajectory or organized by any known rotational period of the Saturnian system (i.e. the phase of the Saturn’s planetary period oscillations or the rotational phase of the D68 ringlet).

Khurana et al. (2018) suggested that these currents are generated by differential zonal thermospheric wind drag acting in the ionosphere at the two ends of these inner field lines. If so, these results show that either Saturn’s ionospheric zonal winds or ionospheric conductivity, or both, are very variable over the ~6.5 day orbital period of these periapsis passes. Our results add to the body of evidence showing that there is a significant and variable dynamical interaction between the material in Saturn’s D ring and the planet’s equatorial atmosphere.

For more information, please see the paper below:

Provan, G., Cowley, S. W. H., Bunce, E. J., Bradley, T. J., Hunt, G. J., Cao, H., & Dougherty, M. K. (2019). Variability of intra–D ring azimuthal magnetic field profiles observed on Cassini's proximal periapsis passes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA026121

Figure 1: (a) The spacecraft trajectory of two example proximal passes. The planet is shown in orange, and the arrowed black lines show model magnetic field lines. The A to C rings are shown in dark blue, and the D ring in lighter blue. The suggested intra-D ring current system is shown in green in panel (b).

Field line resonance in the Hermean magnetosphere: structure and implications for plasma distribution

by Matthew K. James (University of Leicester)

Mercury’s magnetosphere is the smallest and most active within our solar system, providing a unique laboratory for studying magnetospheric physics, where much can be ascertained using ultra low frequency (ULF) waves. ULF waves are a key mechanism in the transmission of energy, momentum and information around any magnetised plasma environment and have been observed in magnetospheres throughout the solar system (e.g. Mercury, Earth, Jupiter, Saturn and Ganymede). The frequencies and polarizations of a certain class of ULF waves, called magnetohydrodynamic shear Alfvén waves, can be used to diagnose the plasma mass loading within the magnetosphere. Shear Alfvén waves are transverse standing waves which exist on field lines bound at both ends to the planet in question, where the perturbed magnetic field is displaced azimuthally around the planetary magnetosphere. These waves are analogous to the waves standing on a guitar string, where only standing waves with discrete frequencies are supported. At Earth, these waves are often driven by solar wind forcing on the magnetosphere in a process known as field line resonance (FLR).

Until recently, it was thought that Mercury's magnetosphere was incapable of supporting such FLRs due to its relatively small size. Our study is the first statistical survey of FLRs in the Hermean magnetosphere; we used magnetic field observations from the spacecraft MESSENGER to detect 566 FLRs within the dayside of the magnetosphere. An example simulation of one such Hermean FLR is presented in the figure below, where the field oscillates with a combination of both the fundamental and second harmonic frequencies.The characteristics of these waves were used to determine plasma mass densities throughout the dayside magnetosphere. We also found that the structure of the resonant waves is highly asymmetric about the magnetic equator, with the largest field perturbations appearing north of the magnetic equator due to the offset of the magnetic dipole into the northern hemisphere of the planet.

For more information, please see the paper below:

James, M. K., Imber, S. M., Yeoman, T. K., & Bunce, E. J. (2019). Field line resonance in the Hermean magnetosphere: Structure and implications for plasma distribution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025920

Figure: Top left panel shows the power spectrum of the poloidal (red), toroidal (green) and compressional (blue) components of a FLR detected using MESSENGER. The majority of the wave power is seen in the toroidal component at 25 mHz (fundamental frequency), some toroidal wave power is also present at 60 mHz (second harmonic). The top right panel is an animation showing how the displacement of the field line (solid green line) might vary with time, compared to the unperturbed field (dashed green line), as it oscillates with a combination of the two detected frequencies at the location of this resonance. The bottom panel contains an animation showing how the electric (yellow) and magnetic perturbation (blue) fields would vary in time along the length of the field line, x.

Measuring a geomagnetic storm with a Raspberry Pi magnetometer

by Ciarán Beggan (British Geological Survey)

As computers such as the Raspberry Pi and geophysical sensors have become smaller and cheaper it is now possible to build a reasonably sensitive system which can detect and record the changes of the magnetic field caused by the Northern Lights (aurora). Though not as accurate as a scientific level instrument, the Raspberry Pi magnetometer costs around 1/100th the price (about £180 at 2019 prices) for around 1/100th the accuracy (~1.5 nanoTesla). However, this is sufficient to make interesting scientific measurements.

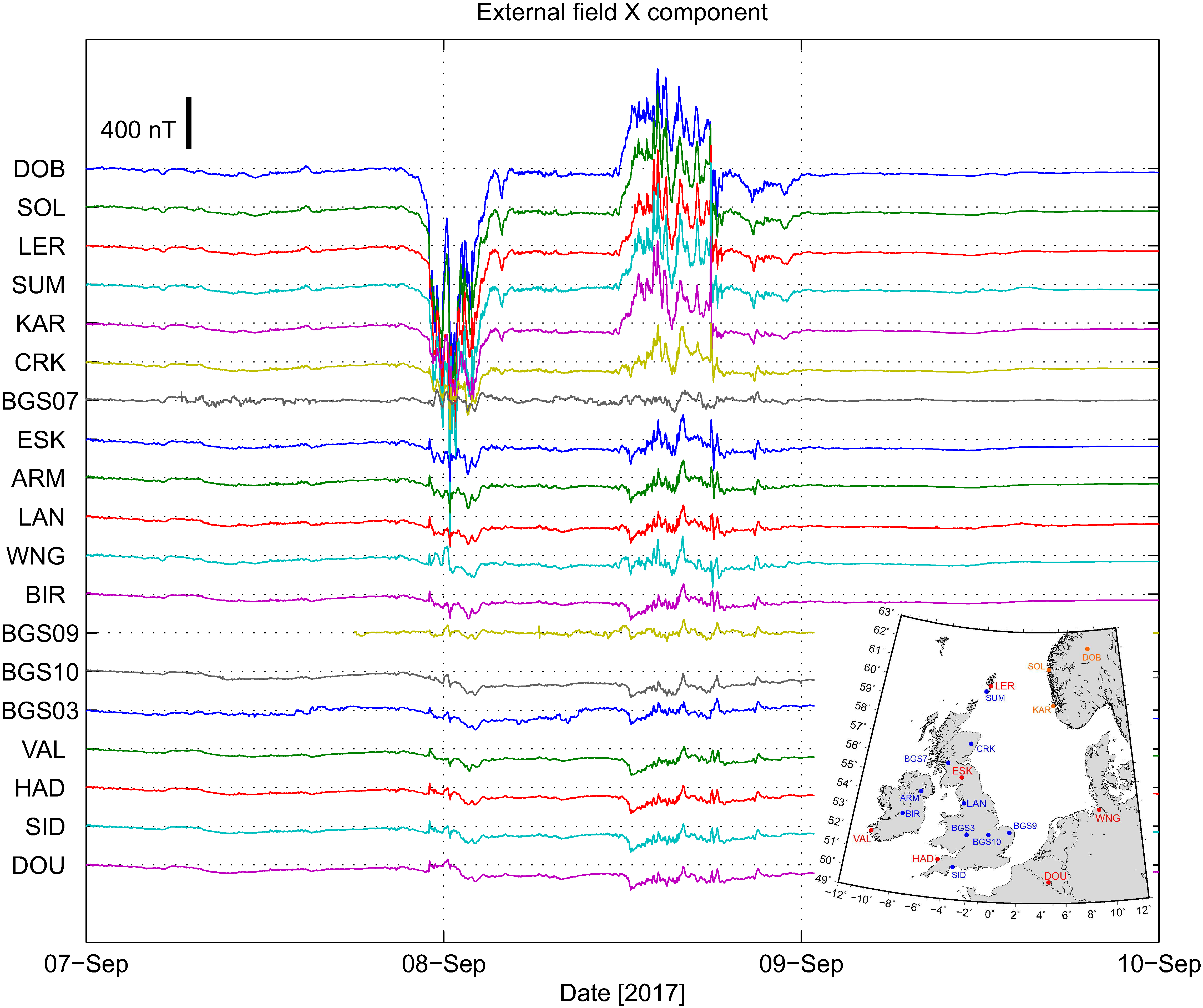

During 2017, a network of 9 Raspberry Pi magnetometers were deployed to schools around the UK from Benbecula to Norwich. On the 8th September 2017 a large geomagnetic storm was captured by the school magnetometers. Using these data and the array of other magnetometers around the North Sea, we were able to recreate the spatial and temporal changes of the magnetic field during the storm in great detail. The two phases of the storm (see Figure) show the westward (night time) and eastward (daytime) flow of the auroral electrojet currents in the ionosphere.

The results are given in more detail in our paper, but we have shown that it is possible to augment the existing professional network with citizen science sensors to fill in the ‘gaps’ for large geomagnetic storms.

Please see the paper below for more information:

Beggan, C. D. and Marple, S. R. (2018), Building a Raspberry Pi school magnetometer network in the UK, Geosci. Commun., 1, 25-34, https://doi.org/10.5194/gc-1-25-2018

Figure: Stackplot of the variation of the magnetic North component of the magnetic field for the geomagnetic storm of the 7-8th September 2017, ordered by latitude. Inset: Map of the locations of the variometers and observatories around the North Sea.

Statistical Planetary Period Oscillation Signatures in Saturn's UV Auroral Intensity

by Alexander Bader, Lancaster University, UK.

Saturn's highly dynamic auroras are generated by electrons precipitating along the magnetic field lines into the planet's polar ionospheres due to currents along the magnetic field lines. Therefore, the aurora provide information about the location and strength of these field-aligned currents. Two types of large-scale current systems have been observed in magnetic field measurements: one a quasi-static system associated with flow shears between plasma rotating at different speeds in the outer magnetosphere. The other significant type are field-aligned current systems rotating according to the planetary period oscillation (PPO) systems. Both the northern and the southern hemisphere are associated with one such system each, superimposed on the quasistatic system and causing roughly 10.7-hour periodic oscillations throughout the Kronian magnetosphere.

Upward and downward field-aligned currents in the northern ionosphere were found to be modulated by rotating patterns imposed by both the northern and southern PPO systems, the latter modulation being facilitated through interhemispheric current closure. The auroral intensity is hence also expected to be modulated accordingly, such that the northern aurora is brightest at roughly ΨN/S = 90°, where the currents have also been shown to maximize. Due to the two PPO systems rotating at slightly different angular velocities, this results in a double modulation.

In this study we analyzed the statistical behavior of Saturn's ultraviolet auroral emissions over the full Cassini mission using all suitable Cassini-UVIS images acquired between 2007 and 2017. This study shows for the first time that both hemispheres' auroral intensities are modulated by both the PPO system associated with the same hemisphere (primary system, Fig. 1a) and the opposite hemisphere (secondary system, Fig. 1b), relatively. The modulation by the primary system is found to be more intense than the one caused by the secondary system. This confirms that both PPO systems' field-aligned currents traverse the entire magnetosphere and close at least partly in the hemisphere opposite to where the generating perturbation is located.

For more information, see our paper below:

Bader, A., Badman, S. V., Kinrade, J., Cowley, S. W. H., Provan, G., & Pryor, W. R. (2018). Statistical planetary period oscillation signatures in Saturn's UV auroral intensity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 123, 8459–8472. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025855

Figure 1: Average northern UV auroral intensity maxima per local time (4/3 h bin size) and PPO phase ΨN/S (20° bin size), shown in a logarithmic color scale. (a) Northern hemisphere auroral intensity ordered by the northern PPO system and (b) northern hemisphere auroral intensity ordered by the southern PPO system. Two Ψ phase cycles are plotted for clarity, the expected locations of maximum upward current are indicated by dashed white lines. On the top and to the side of each 2D histogram the averages of the mean intensity maxima over the ΨN/S and LT dimensions are shown in black, respectively. Separate histograms showing the PPO intensity modulation in the dawn-noon (blue) and dusk-midnight (red) regions are calculated from the parts of the histogram marked with colored boxes and shown to the right side (note the logarithmic intensity scale). The histogram over the full LT range (black) has been fitted with a simple sine (gray). Its maxima are marked with vertical dash-dotted lines, its peak-to-peak (pk-pk) amplitude and the ΨN angle with the highest intensity are given in the top right corner of each panel.

Determination of the Equatorial Electron Differential Flux From Observations at Low Earth Orbit

By Hayley J. Allison, British Antarctic Survey / University of Cambridge, UK.

Electrons trapped on the terrestrial magnetic field form the Earth’s electron radiation belts. The dynamics of these structures can be examined using numerical models such as the BAS Radiation Belt Model. Recent work has highlighted the link between increases in the low energy seed population (tens to hundreds of keV electrons) and high-energy relativistic electron flux enhancements in the radiation belts. However, data on the seed population is limited to a few satellite missions.

Low earth orbit satellites, such as the Polar Operational Environmental Satellites (POES), rapidly sample the radiation belt region and provide a wealth of observations of the electron environment. Here we present a method to utilise this dataset to develop event-specific low energy boundary conditions for the British Antarctic Survey 3-D Radiation Belt Model. Such a method can supply realistic low energy boundary conditions for periods outside the Van Allen Probes mission, with a broad magnetic local time coverage.

Using the low energy POES observations presents two main challenges. Firstly, the electron populations measured by the POES satellites are of low equatorial pitch angle. Secondly, the SEM-2 detector supplies integral electron flux, i.e. including all electrons from a lower energy limit up to a threshold. We used activity dependent equatorial pitch angle distributions, derived from Van Allen Probes observations, to map the POES observations to higher pitch angles and explore two methods for obtaining the flux at various electron energies (differential flux) from the integral flux measurements.

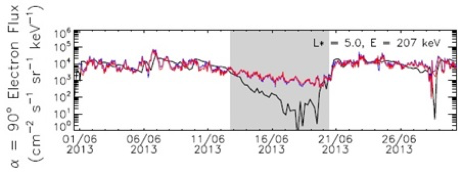

The resulting equatorial electron differential flux values were validated against MagEIS observations and showed an average agreement within a factor of 4 for L* > 3.7 when the assumption that electron flux decreased with increasing energy held (white areas in figure). Variations in the MagEIS flux tend to be reproduced in the converted POES dataset. Periods when the electron flux did not fall with energy (shaded grey) were primarily during quiet times when a lack of chorus wave activity meant that these low energy electrons were not accelerated to >900 keV energies.

For more information, please see the paper below:

Allison, H. J., Horne, R. B., Glauert, S. A., & Del Zanna, G. (2018). Determination of the equatorial electron differential flux from observations at low Earth orbit. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 123. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025786

Figure: Comparison of the Van Allen Probes Magnetic Electron Ion Spectrometer electron flux (black lines) at five L* values, for energies following a line of constant μ = 100 MeV/G and the electron flux determined from the POES observations using the AE-9 distributions for the integral flux to differential conversion (red line) and using the iterative approach (blue line). Grey regions show periods when the assumptions that the electron flux falls with increasing energy were violated.